A Comment on the Ukraine

I’ll be honest. I sat several times to write this and stopped. I made notes. I deleted them.

But people ask my opinion as someone who hosted a conference on the humanitarian cost of the war, who runs a Central European Institute and writes on Global Economics. They have a point. And I do have an opinion. So, today I share my thoughts.

The one year anniversary of Russia’s most recent invasion of Ukraine is a sad day.

It’s a commemoration.

Photo by Olga Subach on Unsplash

Long Story, Short: This is Horrible and Terribly Sad

The war in Ukraine is fundamentally a tragedy. No matter the outcome, hundreds of thousands of people lost – and will continue to lose – their lives[1] and countless families have been broken up. Peoples’ lives and livelihoods and their abilities to maintain their lives and livelihoods have been destroyed.

Millions of people have been displaced. Some 8 million people have been forced into refugee status across Europe and the world and even more are displaced within their own homeland of Ukraine. The toll on families is unimaginable. An estimated 16 million people are now “living” in Ukraine without access to clean water and sanitation.

Human wellbeing is the first and final true measure of a cost-benefit framework and for all those who lost their lives and/or lost their loved ones, the war is all cost and no benefit.

We should pray for those families, friends and all affected and pray that the war ends soon.

Period.

Geopolitics and Politics

This is a case where politics and economics mingle in the messiest of ways. Political science isn’t my field, so I’ll just make some observations and leave the deeper analysis to the experts.

With a topic like this, I feel I should be upfront about my views. In this case, it’s relevant that I’m an American and have a very American view on this. In my opinion, “ending the war” means total and complete victory for the people of Ukraine which means returning to the borders of, say, 1994.

As I see it, the effects of this war are, first, human, second, geo-political and, third, economic. I mentioned the human cost above and for anyone personally affected by war, that really is the first, second and final effect.

But there have been other tragedies in the world with massive loss of human life and human displacement where the US has not gotten involved. Why are we - the Americans - supporting the Ukraine?

The answer is mostly geo-political. The US is supporting the Ukraine in order to keep Russia in check and as a signal or warning to China.

This appears to be the last, best opportunity to stop Russia. After Russia invaded and took the Crimean peninsula of Ukraine in 2014, everyone hoped that Putin’s appetite was satiated. It was not. I believe our top strategists understand that stopping now will only once again postpone the inevitable and give Russia a few years to re-arm and push forward again. So, fight today or fight again tomorrow. It seems the US decided to fight today.

The United States cannot let Russia just take countries from Europe. Russia taking the Ukraine would immediately threaten all other neighboring European countries in the region and Putin has publicly said he would like to have them too. Here I’m thinking especially or Poland, Lithuania, and the others that Putin has explicitly mentioned.

Again, I leave it to specialists in this field to say whether we are doing this well or poorly. I have my own personal views, of course. But, no matter what happens next, the geo-political implications of this war and how it ends are and will be huge. They will reshape alliances and embolden or discourage adversaries of freedom and free people around the world for years to come. The stakes really couldn’t be higher.

One Other Fissure: The European Union

Those high stakes can be seen clearly in Europe. Russian tanks woke up the West Europeans. Period.

The West Europeans, led by Germany, had long been pursuing a very pro-Russian (energy) policy.

Former German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder served on a Russian energy company’s board? He served on the board of a Russian company building and lobbying for monopolistic Russian pipelines? Really? …No comment… Just Google to read more about it. I recommend quality publications only: Wall Street Journal, New York Times, Reuters, etc. It’s just disturbing. And it’s so disappointing.

The Central and East European countries begged and pleaded with the Western European countries for many, many years to develop alternative pipelines. For at least a decade, this was topic number one every single year I visited Hungary, Poland and Romania (a little less in Romania since it has access to the Black Sea). Land-locked countries like the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Slovakia were scrambling for any alternative just to avoid being totally depended on Russian energy. But they lost the argument in Europe and alternative pipelines were not allowed to be built.

Today, as I understand, alternatives are being expedited. Germany reversed its course on a dime and fast-tracked approval for 12 LNG (liquid natural gas) terminals, six of which will apparently be floating terminals and four of those should be finished by the end of 2023. All of them should be done by 2026.

Support for Ukraine is high and strong across Europe today. That’s good. But, that is a volatile situation. The energy costs are high, the sanctions are painful (I think…but in recent days at several conferences on the Ukraine, I’m hearing that “the sanctions hurt Europe” is Russia propaganda, so I’m skeptical and realize that my sources on this are just other news articles saying the same, but not hard figures…hmmm…) and unpopular and every night people see death and destruction on the news. And, normal people just want to it to end. War fatigue is real. It will grow. Every politician will blame every problem they can on the war. The mood of the people could turn on a dime.

Let’s simply hope the war ends soon.

The Economic Impact

Finally, something I’m competent to talk about and, yet, there’s not too much to say. Anyone can see that the economic cost of war is high and negative.

People don’t realize this, but economists actually measure well being in terms of what we call “utility”. Utility is a catch all phrase for what an individual person feels is valuable and important. We say people are “better off” if their utility is higher and “worse off” if it’s lower. That’s it. They make their own private value judgements.

Utility is 100% personal and subjective. One person likes apples, the other oranges. One person gives all their money away to their church and community, the other hoards it under the mattress. Economic analysis doesn’t judge.

But one thing is clear: utility is zero (or negative infinity, if you like) when you are dead or your family members are dead and when the life you were building is destroyed. So, any quality economic analysis will find the war absolutely devastating from an economist’s point of view. As I said, it starts and ends with the loss of human life and destruction of families. There’s little else to say.

The Financial-Macroeconomic Impact in Ukraine

There is also, of course, a financial-economic impact too. That’s probably what most people mean when they ask me about “the economic cost” anyway. So let me turn to that.

It is also totally negative. There is no sense in which “war is good for the economy”. It’s never actually been the case. A single business or person or politician might benefit from the war and some surely do. But war is always bad for an economy as a whole. After all, “an economy” is only a collection of all individuals trying to cooperate with one another. And they would be better off with peace, strong democratic institutions and a well-functioning market.

Let’s start by looking at the fundamental factors of production in an economy. Three main ingredients that go into producing GDP: labor, capital and technology.

Labor

As I mentioned above, people both died and others have been displaced. Many others have been re-allocated to military affairs. From an economic production point of view this is (a) a loss of labor and (b) a misallocation of much of the surviving labor away from productive uses. Both of those things lower production today and in the near future.

For sure, today, those people need to be fighting. But I’m sure they would also prefer to have their old jobs cooking, teaching, building or inventing things or whatever their profession called for.

Capital

Macroeconomics consider capital as the physical stuff labor uses in production. When I teach economics, I use a white board in a classroom with chairs, tables, etc. Those are all capital. My time and teaching is the labor.

Across the Ukraine, buildings, roads, homes, pipelines, and the like have been destroyed and re-purposed. It’s similar to the labor story. This lowers production today and for some time in the future since it takes time to create and build up a stock of useable capital in an economy.

GDP’s Collapse

The World Bank[2] estimates that there was a 45% drop in GDP in 2022. To put that into perspective for those of us in our cozy American homes, US GDP dropped 10% for only 1 quarter during Covid and that was the biggest decline with WWII. So, 45% is huge. Imagine essentially half the US economy disappearing over night. Imagine losing 45% of your own income and livelihood and, more importantly, your ability to generate income and further livelihood.

Some of this also came from an initial restriction in Ukraine’s ability to trade with the rest of the world. Black Sea ports were closed and rail-lines blocked. But that was surprisingly resolved rather quickly and trade has resumed. I suspect Russia capitulated on that in order not to further harm its international reputation. Remember, initially, everyone thought Russia would roll across Ukraine and take Kyiv in 5-10 days. Only after it became clear that this wasn’t the case, that Russia was suddenly looking very bad, and that world opinion was turning against it did Russia agree to allow trade to resume. But, fortunately, it did. This has been a partial lifeline for the Ukrainian economy and for many countries around the world that rely on Ukraine agricultural products.

Technology

Technology, human capital and human know-how are harder to destroy than buildings and human beings. But some of it definitely dies with people. And, this technological and knowhow side of the economy turns out to be the single most important thing for long-term economic growth.

While it’s less of a negative impact today, it is not being developed in any sense and will, in some ways, be the most devastating long-term macroeconomic drawback from the war. With loss of life and brain drain (i.e., people leaving the country), there is loss of knowhow and of human capital. It’s one of the things that policy makers need to keep in mind when the war ends and rebuilding starts. I’ll comment more below.

The Financial-Macroeconomic Impact in Europe

There are three major effects I think about: energy, human, and military.

For Europe, broadly speaking, there is an immediate energy crisis and cost of living crisis. Some of this pre-dates the war and some was made much worse by the war. Both the sanctions and the war itself are raising prices across Europe in addition to bad policy that led to today’s inflation problems generally.

Surprisingly, this effect hasn’t been as dramatic as we initially expected. And I think – and this is bad news – that politicians are rather using the sanctions and the war in Ukraine as an excuse for bad policies that are leading to more inflation and other problems.

Prices were rising pre-war.

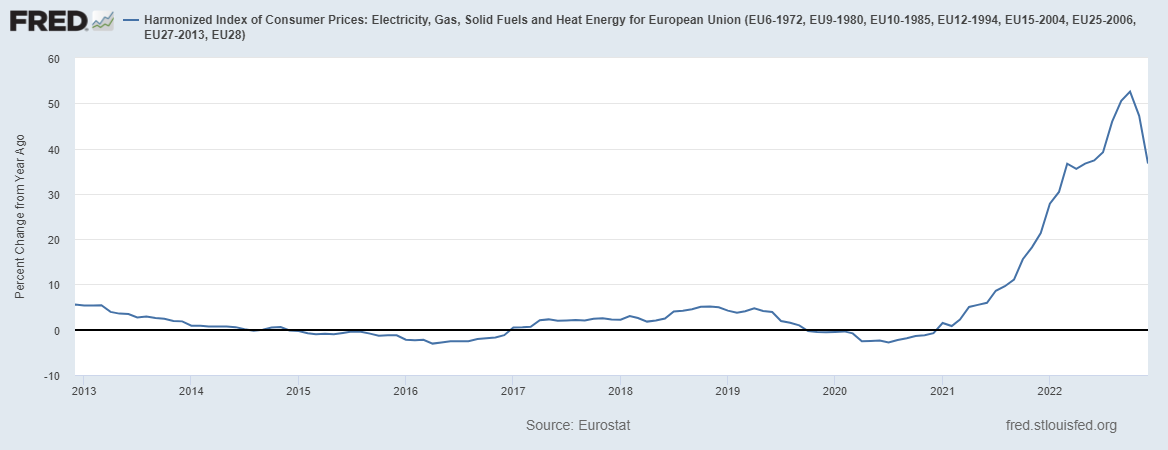

This graph looks pretty dramatic. And it is. This is an index of electricity, gas, fuels and heating energy in Europe[3]. They rose by 50%. That’s harsh. No doubt.

But zoom in to 2021. Look at what happened 2021-2022. The war started in February 2022. These prices had already risen nearly 40% in that 2021-2022 period, pre-war.

The same is true for global commodities.

They were already up 60% in 2021. They’ve been dropping since January/February 2022 after the war started.

We can debate if these were driven by supply chain problems or bad policy or something else. But, whatever their cause, it wasn’t the war. They are a pre-war phenomenon.

We were right to be worried about the war amplifying all these effects. I too thought the crisis would be much worse. But it wasn’t.

Military

Every country in Europe has increased military spending and has committed to doing so over the coming year(s). Defense is important and necessary. Without a safe, peaceful society, nothing else can flourish.

But, from an economic growth perspective, all government spending crowds out private spending and diverts resources away from private uses. In this case, it diverts funds into military goods and services. This may (or may not) have a short-run stimulative effect on the GDP, but it definitely has a long-term cost due to the higher taxes needed to finance it and the diversion of resources away from more productive uses. Hence, it’s a necessary but otherwise negative effect of the war.

Both of these challenges – inflation and military spending – are important for all affected economies, but one challenge trumps all others for Ukraine’s immediate neighbors: migration and refugees.

The Macroeconomic Challenge of Migration and Refugees

The refugee crisis is first and foremost a humanitarian crisis. 8 million people dislocated so far (and even more internally). This means broken families, hungry children and struggling mothers. It is a tragedy and will scar those people for life.

Macroeconomically speaking, suddenly accepting 2-5 million refugees, as countries like Poland have done, is very expensive. First, there is the immediate cost of processing, feeding and helping them. Second, Poland, for example, has allowed about 1 million refugees to work. The extra supply of labor will depress wages and when foreign workers replace domestic ones and/or harm wages, social strife is usually soon to follow.

Fortunately, in Poland, Hungary, Romania and the other neighbors, unemployment was extremely low pre-Covid. And, like everywhere else in the world, there are many mysteriously missing workers. So, the extra labor help is likely welcomed and doesn’t seem to be depressing wages much yet.

But GDP per capita necessarily falls when the “capita” part increases. Of course it raises GDP as well, but proportionally less than the increase in people, hence the ratio always falls in the short term. Add that to the social support costs for the host nations and this will become a growing issue over time. If the global economy slows, as interest rates rise to fight inflation over the coming months, the refugee/migration inflow could become an additional pain point socially and economically across Europe.

Many refugees are indeed travelling through the neighboring countries of Central Europe, aiming for Western European countries instead. This means the effects of this migration are somewhat dispersed. Nevertheless, a country like Hungary has a population of about 10 million and about 1 million refugees have entered. Most are passing through but that’s 10% of the Hungarian population. If Poland took 2-5 million (as I mentioned above), that’s again potentially 10% of their approximate 37 million population. Those migration flows can have huge effects on local services, businesses and the local labor markets, especially where they stay and work.

Still, to-date, popular support has remained high and the refugees are currently warmly welcomed in all those countries, at least to the best of my knowledge. People proudly talk about the families they’ve housed temporarily in their homes and apartments across the region. It’s been heart-warming to see.

But stability based on the goodness of the human heart can be fragile. We just need to keep an eye on any cracks in the foundations of that popular support.

(Re-)Building Ukraine

Let’s end on a positive note: one day the war will end. Let’s hope and pray that it ends sooner rather than later.

When it does, there seems to be wide-spread support for an effort to modernize and (re-)build Ukraine. Here, I intentionally used “(re-)”. The clear intention seems to be to “finally” build Ukrainian democracy the right way. That seems to be the intention of the Ukrainian people and is certainly the hope of the world’s policy leaders.

Ukraine did not fare well post Soviet Union. It struggled with corruption and other problems stemming from weak (or non-) democratic institutions. It still struggles with those challenges today.

Economically speaking, we know what countries need to grow and prosper long-term: stable political systems with the rule of law and strong property rights. All that is captured under the broad phrase “strong democratic institutions”. And that’s just the medicine being prescribed for Ukraine from every policy corner of the globe.

Those focused on politics, security policy and geo-politics, the end goal is to get Ukraine safe, democratic, stable, into the European Union and NATO. I guess you could say the thinking is “let’s settle this once and for all”.

Entry into NATO includes these things quite explicitly. The preamble to the Washington Treaty – NATO’s founding document – says “The Parties to this Treaty… are determined to safeguard the freedom, common heritage and civilisation of their peoples, founded on the principles of democracy, individual liberty and the rule of law.”[4] Ukraine has been unable to join NATO since the 1990s because it hasn’t met the conditions. Militarily it’s been a partner, but it couldn’t meet the democratic institutional demands.

Likewise, the European Union requires these same things and additionally a stable economy. They EU has too many treaties to quote, but the same principles are there.

From a macroeconomic perspective that is key. Ideally it comes from the bottom up meaning from the Ukrainian people. When that happens - with external guidance and support - it can stick and succeed long term. To the best of my knowledge, nearly all attempts of external actors to develop a local country’s “democracy” have failed. Only time will tell which is the case in Ukraine. I personally hope the war and the need to be under the Western defense and economic umbrella motivates enough of the Ukrainian leaders - both official and unofficial - to want to do this right.

In any case, the steps are clear. First, an economy requires property rights. The most fundamental of which is your right over your own body. This is why things like slavery or exploitation are antithetical to a well-functioning market system based on free people.

Once it’s clear that you own your own body, then you immediately have the right to rent out your time, called your labor. I invested in my body with a Ph.D. and today I rent my intellectual services (economics lectures) to Quinnipiac University (QU) which sells them to students.

But notice, a number of things happen for these transactions to take place. The property right must exist and be clearly defined. It must also be transferrable. I have to be able to legally sell it to QU which legally sells it to students.

This is true for all goods and services. When I walk in to buy a Coke at the gas station, the station clearly owns it. After I buy the Coke, I legally own it. A property right over the Coke was just transferred from the store to me. The store owner can’t now claim it back. If they try, we can both go to court and in a country with sound legal institutions – collectively called “the rule of law” – we can adjudicate our disputes through some reasonably fair and dispassionate process.

That all breaks down when democratic institutions are weak. If the local police - or local thugs - can just beat me up and take the Coke, I’m less likely to go in and buy it. If they can take it from the store, the store is less likely to hold inventory. If I own my body on paper, but local thugs, mafia and oligarchs can still take my income and tell me where to work, what to sell, and so on, then I only own myself on paper, not in reality. Why would I invest in a Ph.D.?

Those are the problems of corruption and the breakdown of democratic institutions (namely property rights, individual rights and the broad rule of law). But when they are in place, people invest in education, inventions, in their businesses and so on and economies – which again are just collections of human beings – thrive.

So that’s the hope for Ukraine. This war has been horrible. There are stories of mass graves. The Russians are intentionally bombing homes, churches, hospitals and schools.

But if any good is to come of it all, the Russians will be driven off of all Ukrainian territory (defined pre-2014) and Ukrainians will come together to form a country ruled by laws and upheld by appropriate democratic institutions. If that happens, the Ukrainian people will flourish and share their talents with the world. They will join NATO and join the European Union and this tragedy will only be something taught as a warning to children in classrooms who will question that such horrors could ever really have happened. What a blessing that would be!

Thank you for reading and thank you for all of you supporting the Ukrainian fight for freedom.

[1] As of today, February 24, 2023, I understand the estimate is about 300,000 dead. I think the breakdown is about half on the Ukrainian and half on the Russian side.

[2] World Bank: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/ukraine/overview

[3] Link to graph in FRED: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/ELGAS0EUCCM086NEST#0

[4] NATO Washington Treaty: https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_17120.htm