A Less Liquid New Year

Photo by Chester Ho on Unsplash

This past week saw the central banks in the US, England and the European Union raise interest rates by a half percentage point and announce very similar prognoses for the coming year. All of them see rates continuing to rise and stay high, economic growth to slow, and for inflation to fade but die a very slow death.

In all three cases, the central bankers publicly reaffirmed their commitment to a 2% inflation target. That’s noteworthy for a few reasons. First, people were speculating – dare I say hoping – that the central banks would raise their inflation targets to 3% or 3.5%. Second, it tells everyone that the central bankers are not going to “work on reducing inflation some”, taking us down to 4-5% which would be more comfortable than the 7-10% it’s at now. No, they plan to get us all the way back to 2%. That’s a commitment.

The US Federal Reserve

US Fed Chair Powell explained that he and the other members of the FOMC expect the Fed’s federal funds rate to be “in the 5’s” next year. By the end of 2023, 10 of the 19 FOMC participants expect the federal funds rate to be at 5.125% and 5 of the 19 expect it to be at 5.375%[1]. That means it’ll be in the 5’s and stay there for the year for sure. For 2024, 14 of the 19 say they believe it will remain at 4.125% or more.

After this week’s increase, the rate sits at 4.5%. That means the FOMC will have some flexibility to raise it a quarter point or half point at their February 2023 meeting followed by smaller increments thereafter or a pause. It’s hard to say precisely, but it’s clear it’ll rise further and stay high all year.

It’s the “stay high all year” part that Powell emphasized repeatedly because he wants everyone to understand that no pivot is coming. The Fed is committed to returning inflation all the way down to 2%. That public commitment will be especially important in the Spring when the Fed expects unemployment to rise as the economy slows and inflation falls. At that point, the pressure on the Fed to lower rates and ease their grip on financial conditions will be tremendous. But as Powel and company know, that’s exactly the trap central banks fell into in the 1970s leading to both high inflation and high unemployment. That exactly the trap he intends to avoid on his watch.

The European Central Bank (ECB)

ECB Chair Christine Lagarde made similar statements. The ECB decided to raise all three of its policy rates by half a percentage point and also announced that it would continue raising rates and keep them high through next year. Again, she reminded the public that the ECB will continue this until inflation returns to its 2% target.

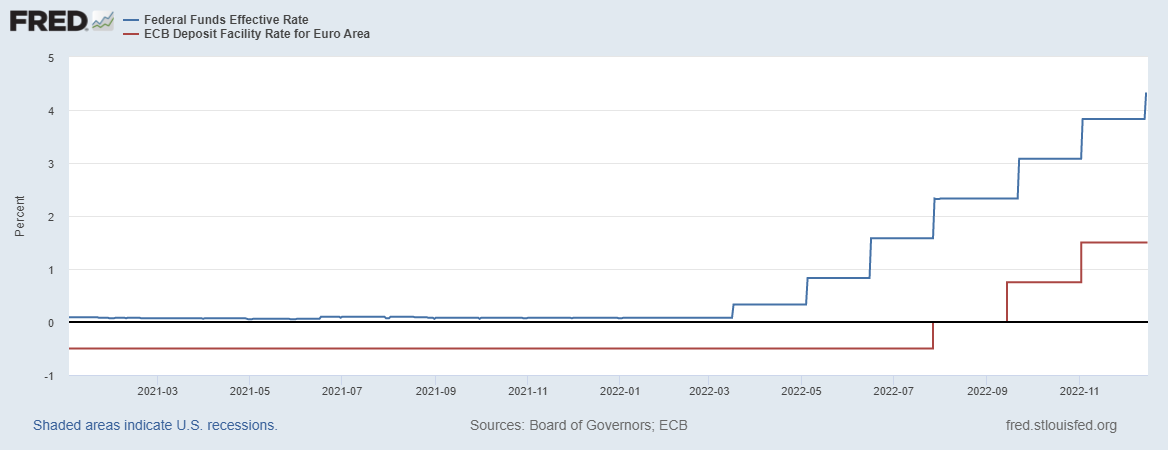

The ECB however started rate hikes much later than the Fed (see graph below). The ECB therefore has further to go in the coming months.

Both banks held rates near zero until this year. The Fed started raising rates in Spring this year (blue line) and they are already at 4.5%. The ECB only started raising rates in July (red line) when it took the lowest rate first from negative 0.5% to 0%, then to .75% in September, 1.5% in November and now 2% in December[2].

Additionally, the ECB is just now announcing that it will start reducing its bloated balance sheet in the Spring, something the Fed has been doing since summer. This matters because it means the bank won’t be buying as many bonds from the market, an act that injects liquidity into the financial system and props up the price of bonds, keeping interest rates suprpessed.

The ECB projects that “[k]eeping interest rates at restrictive levels will over time reduce inflation by dampening demand and will also guard against the risk of a persistent upward shift in inflation expectations”[3]. It will be painful but it will eventually defeat inflation, albeit slowly.

And notice the persistent concern with “inflation expectations”. All these policy announcements, stern language and projections for next year are efforts to keep expectations anchored to low inflation. If people ever start believing high inflation is here to stay, then all bets are off. Getting inflation under control will be much, much harder and all central bankers know that.

The ECB projects that this tough-love policy will take Euro inflation from its current 10% down to 6.3% in 2023, 3.4% in 2024 and finally 2.3% by end of 2025. It believes that there’s a contraction in the Euro area economy now and that it will continue through the first quarter of 2023. It expects GDP growth to average 0.5% for 2023 overall.

The US Fed sees US growth similarly. It projects growth to be around 0.5-1% for 2023. Again, the US is a little ahead of Europe, suffering negative growth earlier in the year with an estimated 0.5% growth rate for the US economy this year (2022) compared with Europe which enjoyed nearly 3.4% economic growth this year.

The Bank of England (BOE)

The English are also suffering 10.7% inflation (down from 11.1% in October). The BOE expects negative GDP growth in the final quarter of 2022 and the UK economy “to be in recession for a prolonged period”[4].

The latest 0.5% policy rate increase sets the BOE rate at 3.5%, somewhere between the ECB and the US. And, it also expects to continue increasing rates until inflation returns to its 2% target over the coming two to three years. Fundamentally the points made by the BOE are all the same as in the US and Europe.

In many ways the English economy is ahead of the US and Europe in terms of facing hardship. Unemployment has been rising slowly and today stands at 3.7%. That is still historically low but, like US and European unemployment, is also starting to creep up.

On a positive note, all the central banks noted that global supply chain bottlenecks appear to be easing. That helps the flow of goods and puts downward pressure on prices, adding some small relief.

A Less Liquid World

All these policy stances mean one thing for sure: a less liquid world in 2023.

Liquidity is a measure of how “spendable” something is. Traditionally you could think of cash. Cash was the most liquid asset and all other assets were measured in terms of how quickly they could be converted into cash. Your checking account was considered more liquid than your savings account which was probably more liquid than your retirement or investment account.

The primary reason economists think people hold liquid assets is to pay for your goods and services (e.g., groceries, gasoline, your rent or mortgage and so on). Otherwise, you’d put that liquid asset into something less liquid but which pays a higher return, like a retirement account.

The interest rate is generally considered the “price of money”. It is the true cost of holding cash since each dollar you hold is giving up the interest or return it could be earning in your bank account or investment.

All these central banks’ policies directly raise the cost of holding “cash” (or any highly liquid asset) by raising the policy rate. Private banks and other financial institutions borrow and lend money between themselves at the policy rate (plus a little something).

When the central banks raise rates, the banks and financial institutions can borrow or lend at that higher rate. As a result, they require a higher rate of return on any other investment they make. If a new investment doesn’t earn them at least what the central bank is paying, then they may as well lend to the central bank.

A year ago, the Fed was paying them near zero for their money, so any investment with any return was a good investment. Today, those same investors can get 4% from the Fed or by lending to other banks, so they need 4% or higher returns from their other investments. Overall this means less investment in the economy since it’s harder to find investment opportunities paying these higher returns.

When interest rates rise, consumers in the economy also consume less which is equivalent to saying they hold less liquid assets (since those are needed to purchase consumption goods). We take out fewer loans to buy cars and run up less on our credit cards. If we have money, we put more of it in our savings accounts and keep less as cash. All that means less spending. For the same income, you can’t both save more and spend more at the same time. Spending and savings are two sides of a seesaw. More of one necessarily means less of the other.

When interest rates are low, economists worry that people invest in a lot of risky opportunities that are a waste of money (think FTX in 2021/22 or house flipping in 2007/2008). Those risky investments are worth it when money is cheap but the misallocation of funds eventually blows up (think FTX in 2022 or house flipping in 2008) and lead to economic problems. It’s this sense in which low interest rate periods are thought to sew the seeds of the next crisis.

But cheap money also stimulates the economy by encouraging people to hold more liquid assets and spend them. The danger, of course, is that the stimulus overheats things, driving demand for goods and services up faster than they can be supplied. That is what happened in the past 2 years and led to the inflation we see today.

It follows, then, that when interest rates rise, they will have the opposite effects. With interest rates higher, money becomes more expensive. That means it’s more valuable and more scarce. Financial institutions will be more careful about the business investments and personal loans they make, scrutinizing opportunities much more closely. Higher rates will lower consumption and contract all investment – the good and the bad – and that slows economic growth overall.

And that’s how central bankers intend to fight inflation, by slowing economic growth. Recall the ECB’s statement that “[k]eeping interest rates at restrictive levels will over time reduce inflation by dampening demand”.

Global Liquidity and Exchange Rates

There’s another aspect to the fact that higher interest rates make money more valuable and scarce that is worth note. Higher interest rates usually strengthen a country’s currency. This higher interest rate environment will affect global currencies.

Imagine the global currency market as a big open field where different currencies can be compared to each other. The ones paying higher interest rates are more valuable than the ones paying lower interest rates. Higher interest rates, all else equal, raise a currency’s value relative to others. Inflation, by the way, does the opposite.

If the US were alone in raising interest rates, the US Dollar (USD) would strengthen relative to other currencies. Indeed, we saw the USD strengthen for much of the year as the US began raising interest rates sooner and faster than other economies. This was helped by the US being a safe haven for global investors.

Inflation – in isolation – should reduce a currency’s value. But it seems that, over the past year, markets correctly saw that US inflation, while rising, was likely to subside sooner than inflation in other countries. So, the rise in the value of the dollar was reinforced by rapidly rising interest rates and expectations that the Fed would get inflation under control faster than other countries.

Both the interest rate and the US-safe-haven effect can be seen in this graph. The red line is the US policy rate (the Federal Funds Rate) and the blue line is the broad index of the USD (a higher index means a generally stronger USD). In the housing crisis of 2008-2009, even though the interest rate fell dramatically, the USD strengthened. That’s primarily the US-safe-haven effect. Even though the crisis started here, the US was still the relatively strongest market and safest place to invest. Recall, for example, Iceland, Ireland, Hungary, Greece and others all neared collapse while the US did not.

Additionally, the interest rate and inflation effects are relative to other countries. In 2008/09 we can see that too. The US interest rate dropped – which should weaken the USD – but interest rates dropped in every major country at the same time, neutralizing the relative effect on the USD.

Following the 2008/09 crisis we entered a new, post-crisis world where every country kept interest rates near zero and central banks struggled to get their inflation rates up to their 2% targets. That’s seen in the 2009-2016 period in the graph.

The USD began strengthening when the US started raising rates in 2016 (and actually a little earlier). Central bankers called that period of 2016 – 2020 a “normalization” of policy since the normal state of affairs is one where we have a positive interest rate and inflation around 2%. We thought we were finally returning to normal and would be there for awhile.

When Covid hit, we saw the USD index spike again for the same reasons we saw it in 2008/09. That was the US-safe-haven effect. Every investor in the world wanted their money in the US to keep it safe.

This last year has seen a significant strengthening of the USD once again. The most plausible explanation is that the US Fed is raising rates faster than other central banks, so inflation will fall faster as well. Both those effects strengthen the USD. Add to that a war in Europe and other post-Covid economic challenges and the US is again the safest place to invest which adds wind to the currency’s proverbial sail.

It only stands to reason that we will therefore see a reversal of this trend in the coming year or two. The US Fed has already raised rates. It might go from 4.5% today to 5% or 5.5% but not further. So it’s nearly done raising rates and inflation is already down to 7% from 9% this summer and will hopefully continue further downward. European inflation is still high and the ECB is just committing to higher rates now.

That means, over the coming year, the ECB will be raising rates while US rates will be relatively constant. All else equal, that should strengthen the Euro relative to the USD. The safe-haven effect will still help the USD’s value globally because, as the world enters recession, the US will again be the safest place to invest. So, my best guess – and this is not investment advice, just observation – is that the USD will lose some of its strength over the year, but not drop as dramatically as it rose.

A slightly weaker USD will mean some support for US exports – since a weaker USD makes them relatively cheaper – and generate some headwind against imports. That should have a mildly stimulative effect on the US economy since exports are goods we produce at home.

Conclusion: A Return to Normal

It will be a tougher financial year next year and everyone expects that situation to remain while the major central banks work to get inflation to 2%.

The effect will be to slow consumer spending and business investment which is what policymakers are aiming for. That slows demand and lowers prices, fighting inflation. This pulls back the overstimulation those same central banks caused in the first place, but it tightens the screws on everyone equally which is the hard price we all pay for the past years’ money mismanagement.

All that should slow economic growth and I expect generally to see a weakening in the USD relative to other currencies as other central banks catch up with US rate hikes.

I’ll close with this. We thought that we were returning to a normal policy world just before Covid. That was good. Zero interest rates are not normal. They over stimulate the economy and encourage misallocations of money.

Here’s a graph to remind us all just how far from normal we had gotten post 2008.

Yes, you read that right. That graph starts at 1700. The Bank of England was founded in 1694. It was a private bank then and continued as such until 1946 when it became part of the government.

The fun thing about including the BOE’s policy rate is that we have data for it back to before the United States was officially founded in 1776. And look at the policy rate. It was 5% for about a hundred years. It fluctuated between 2.5% and 6-7% for another hundred years (hitting 10% a few times).

The US policy rate – red line – starts around 1950. The high inflation period jumps out in the 1970s for both England and the US. The green line is the newcomer, the ECB’s policy rate, starting with the birth of the Euro in 1999[5].

While the 1970s period is clearly an anomaly, so is the post 2008 period. You just do not see negative interest rates anywhere in the world throughout most of history. There were academic and policy-circle debates on whether it would even be possible to have zero and negative policy rates and what it would mean. The Japanese have had negative rates since 2016 and still have them today. But there is no sense in which anyone considers that normal. The Japanese have been unsuccessful at stimulating their economy since about 1990.

So, yes, we are going through a rough period. Yes, the government policy makers and agencies blew it financially during Covid and we are all paying a hard price for that now. But in the end, we might be moving back to a more normal world.

With inflation at 2%, policy interest rates should be around 2-3% and market rates should be a bit higher than that. Let’s hope we get there soon and stay there for a while. That would be a period of stable currencies, less risky investments and, hence, less financial cycles. Ideally it would also be a period where we’d build stable economic growth on solid ground.

Now that our monetary authorities are finally getting their houses in order, we just have to keep our fiscal houses – the US Congress, UK Parliament and EU bureaucrats – from over spending, running up debt and blowing the whole thing.

EDIT: An earlier version mistakenly said the next Fed meeting is in January 2023. It will be in February 2023.

[1] 2 of the 19 saw it below 5% at 2.87% and another 2 saw it at 5.625%. See HTML version of the report: https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/fomcprojtabl20221214.htm

[2] Note the other rates are .5% and .75% higher than that base (deposit) rate, so they are now 2.5% (refinancing rate) and 2.75% (marginal lending rate) respectively. For those interested, the explanation of those rates and their data are here: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/stats/policy_and_exchange_rates/key_ecb_interest_rates/html/index.en.html

[3] First paragraph of the ECB statement: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pressconf/shared/pdf/ecb.ds221215~db4079c498.en.pdf

[4] Second paragraph of the Bank of England statement: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/monetary-policy-summary-and-minutes/2022/monetary-policy-summary-and-minutes-december-2022.pdf

[5] It can’t be seen in the graph but the Bank of England’s rate actually ends in 2017. It’s now called their “base rate” but for graphing purposes I wish they’d continued it in the same graph.