Debts, Deficits, and the Economy

The debt ceiling debate is front and center once again in American political life. So, I thought I’d cover some basics on debts, deficits, and the economy.

The Basic Macroeconomics of Government Finances

Basic economics thinks of society (or “an economy”) as a collection of individuals trying to do the best for themselves. Given their resources, they try to achieve their own desires and dreams based on their own views, values, and objectives. They do some of that individually and some of that together.

When people pursue their objectives individually, we usually think of free people making mutually beneficial exchanges. That’s sort of what people think of as the standard purview of economics. And it is in many ways, but it’s not my focus today.

When people pursue group objectives, they can do so either through private groups (think of associations, NGOs, non-profits, churches, etc.) or through the government. That is my focus today: government and government financing.

One thing that makes governments unique is that governments have no source of revenue of their own. Government revenue is taken from the people over whom it governs (or whom it represents, to be positive about it).

When the government wants to spend money, it has three sources of finance available: (1) tax today, (2) borrow today, and/or (3) print money today. That’s it[1].

The second two could actually be called “tax tomorrow” so that really there are just two sources: taxes today and taxes tomorrow. To see this, imagine a government that wants to spend $10 (or $10 billion) this year.

Option 1 says, raise taxes by $10 this year and use that money to pay for the $10 of spending. Done. Of course, I’m ignoring here that there’s a cost to using the government. You have to pay people to collect the taxes, administer them, disperse them, etc. And, the bigger the government, the bigger is that cost. In reality you have to raise taxes by more than $10 to actually have $10 to spend. We’ll generally ignore that, but it can be non-trivial for big governments.

Option 2 says, borrow $10 this year, use it to finance the $10 of spending this year and then next year repay the $10 plus interest. To make it simple, imagine $1 of interest so, next year, the government owes $11 to those it borrowed from. How does it finance that $11? Same three options: taxes, borrowing, or money printing.

Option 3 says, print $10 this year and use that to finance the $10 of spending this year. The problem with money printing – as we all painfully learned recently – is that it causes inflation about 6-18 months later. Economists literally call the resulting inflation an “inflation tax”. And, based on the timing, it usually comes about a year after the spending.

In the end, the citizens of that particular country pay for this. There is no escaping it. True, the inflation tax is paid by everyone holding that country’s currency. In the end, everyone else in the world can drop USD if they want, but American citizens can’t, because it’s our government’s currency and the only legal tender accepted to pay taxes which all Americans must pay. Hence, in the end, we are the only ones unable to escape the US inflation tax.

Once again, in the final analysis, the citizens of the country end up being 100% responsible for their own government’s debts. Look at any country that ran into a debt crisis. To pay the debt the government usually inflates, raises taxes dramatically, freezes bank accounts, cashes out pension funds, etc. It’s a mess. The US won’t get to that point anytime soon. But, the lesson - we seem to forget day to day - is that we are 100% responsible for every penny our governments spends. The accurate measure of a government’s financial burden is the spending.

Debts and Deficits

The “government deficit” is how much the government needs to borrow to finance spending. For a person, it’s literally how much you had to put on your credit card each month to cover expenses you didn’t have enough income for.

For governments, we usually focus on the “primary” deficit which is taxes – the government’s income – minus spending, T – G. This is the core engine driving deficits or surpluses over time. When you spend more than you bring in, you have to borrow[2]. Governments are the same, and government debt, just like your personal debt, is just the accumulation of all those monthly deficits.

Going beyond the primary government budget, broader accounting includes the various sources of funding today: borrowing, money printing, and taxes. From that they finance spending (G) and count the repayment of past debt plus interest.

If you think about it, in this broader budget sense, there’s never “truly” a government deficit. In the end borrowing + money printing + taxes = spending plus debt payments. That’s actually always equal. For this reason, again, government spending is the true measure of the financial burden being generated on the society at any point in time: Spending = borrowing + money printing + taxes – debt payments. That tells you how much additional financial burden the government created this year.

It’s important to note that, because fundamentally the government’s ability to finance is based on the citizens’ ability to pay, we often measure government debts and deficits in terms of percent of GDP. The idea is the same as when you consider buying a big item like a car or a house. You figure out how much debt relative to your income you can likely handle, how much you think your income will grow over time, and so on when determining whether a given mortgage is feasible for you. Similarly, the economy’s GDP is the income of the people, hence deficits and debt-to-GDP-ratios tell the government how much financing the citizens can likely bear.

A traditional rule of thumb was that, for most countries, government debt over 80% of GDP is dangerously high. Countries often have a hard time paying that back. The European Union, when it formed, had all the new members agree to the Maastricht Treaty which said they would keep government debt to 60% or less of GDP and annual deficits below 3% of GDP. These were viewed as key benchmarks to ensure a healthy economy and healthy government-to-private-economy balance.

Where is the US Government Budget Situation Today?

This is Figure 1-1 in the US Government’s own Congressional Budget Office report. The newest report will come out this summer, so these numbers are from the July 2022 report[3].

There are many interesting (disturbing) things about these graphs.

First, we aren’t quite in as bad financial shape as we were following WWII. We talk about it as if we were, but we aren’t. We are in the worst financial shape since WWII, but we were actually a little worse off financially at that time. At least as measured by debt to GDP.

Second, one clear difference between WWII and today is that the debt in the 1940s was incurred to finance a war. Today they are resulting from policy choices we are making. A person living in the 1940s could easily have imagined that debt to GDP would decline once the war ended. And it did. It took almost 30 years, say, from 1945 to 1975, to get it fully down again.

That’s a “one-time shock” in economics lingo, and as long as policy and government spending stays relatively controlled and the economy grows, eventually the debt to GDP ratio declines. In personal terms, if you buy a house, then keep your spending under control, and your income grows over the years, slowly you pay it all off in time for retirement.

When the debt is driven by policy choices, however, it’s much harder to pay off. High debt-to-GDP ratios don’t just end. As a matter of fact, there’s a reason there are so many jokes that the only place we find immortality on earth is in government programs.

Third, or part II of the second point, is that the projections going forward are for things to worsen. Once again, our own government’s projections are that the situation will only get worse from here. That should be very alarming for everyone.

We can see these three issues in Figure 2-1.

If you just look at the level of the blue line (Outlays) this says that in 30 years government spending, as a percent of GDP (i.e., scaled over time), will be as high as it was during Covid, the biggest crisis since the Great Depression or the 1918 pandemic.

This assumes no other big shocks like the great recession of 2008/09 and Covid. Something as big as Covid is unlikely to occur again in the coming 10-20 years, but a serious recession is certainly possible. That means, this is actually an optimistic projection. That’s a bit scary, to be honest.

Over time, as you might know if you’ve ever lived off your credit cards for a while, interest payments grow as a proportion of your monthly payments. That’s true for government spending and debt as well. You can see it in the top part of Figure 1-1 growing at the end of those projections.

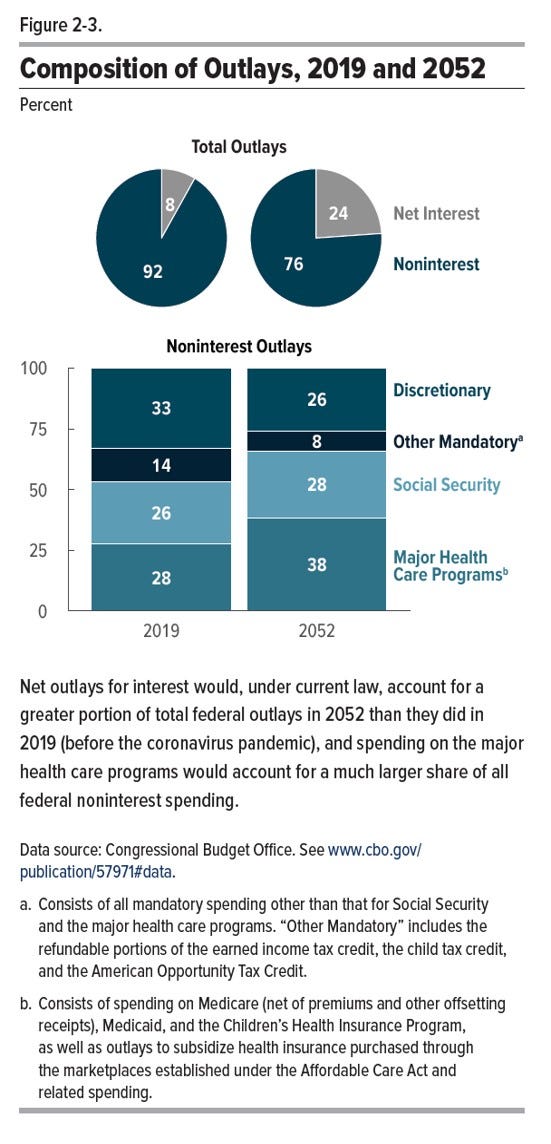

The next graph shows the composition of outlays in the US over the coming 30 years.

Over time, interest payments will grow from 8% of outlays today to 24% by 2052. The other piece that grows is called “mandatory obligations”. That’s what we have already committed to by law. Major health care programs, for example, grow from 27.7% to 38.2% of government spending, a 38% increase in their proportion of the budget.

Discretionary spending must, by definition, fall (by 21%) as a proportion of the budget. That is the part we usually shout and argue about in political debates. That includes money for defense, environmental programs, educational programs, and the like.

It helps explain why entitlement reform is a major topic, albeit also often the proverbial can kicked down the road. But, that road gets shorter every year, and our political leaders will have to confront it eventually. It does suggest to me that political fights will get tougher in the coming years as politicians fight over a shrinking pie of discretionary resources.

Can’t Economic Growth Save Us?

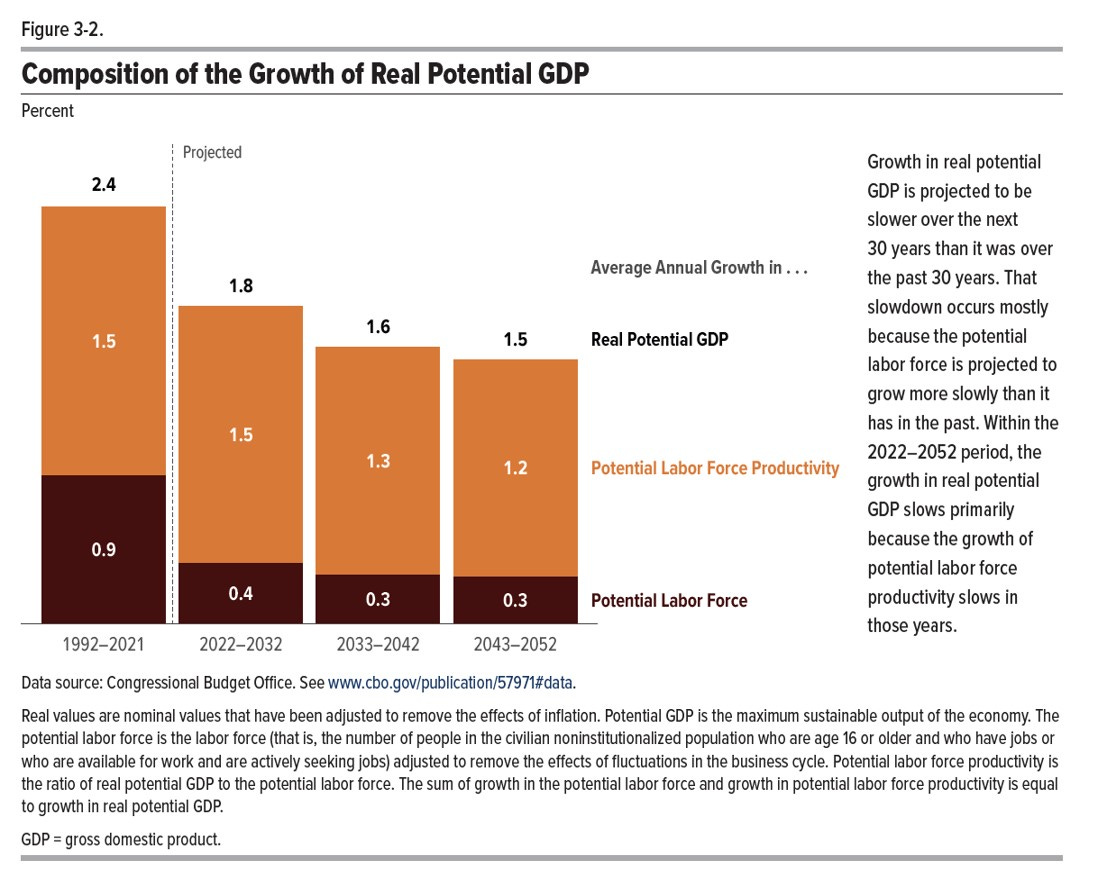

The final and possibly worse problem is that our own government expects GDP growth to slow and remain slow for the coming 30 years.

Figure 3-2 shows the composition of growth of real GDP. Potential GDP is the “ideal” estimate of GDP when everything runs smoothly.

For an economist, this is by far the most disturbing picture. The reason is that almost nothing matters more than long-run growth. But let me focus here on the connection between economic growth and the debt issue.

GDP growth matters in this context, because GDP is our collective income, and hence determines our ability to pay the debt. Debt is projected to rise as a percent of GDP, because we have committed to growing spending – most of it on mandatory entitlements – faster than revenue every year and because GDP isn’t expected to grow as much.

Our government’s own plan is to grow spending by 35% over the coming 30 years but only grow revenue by 3%. And they plan on economic growth slowing from 2.4% over the past 30 years to only 1.5% or 1.2% over the coming 30 years. Everything about that scenario is bad.

Some Macroeconomic-Financial Problems

I’m not sure I believe all these predictions. When speaking publicly, I always use CBO numbers because everyone can look them up, and, equally important, they are what our own government says about it’s own plans and expectations.

I’m not sure about the GDP forecasts. That projected GDP slowdown is a bigger problem than the debt. If that is the current forecast, we need to seek policies that allow the economy to grow faster.

As for debt, there is no hard rule for what level of debt is acceptable and considered healthy. The Maastricht criteria, as mentioned earlier, suggest the rules that used to be considered normal. And, you can even see it in US data. Figure 1-1 shows that, other than WWII and the last 20 years, US debt was generally under 50% of GDP.

In 1992 there was a major political upheaval over US debt-to-GDP that followed the “unacceptably high” budget deficits of the 1980s. That led to President George H. Bush to capitulate on raising taxes, and then lose an election over “read my lips, no new taxes”. He raised taxes precisely because everyone thought the financial situation looked so dire as debt neared 50% of GDP.

The public was worried and the situation was so bad that a Democratic President (Clinton) and Republican Congress (Gingrich) agreed on a major overhaul of a number of government social programs like unemployment and welfare,q and a host of other things. This led to eventual budget surpluses (see top part of Figure 1-1) around the 2000s.

When I started teaching in the early 2000s, there were financial debates about government deficits and debt due to the war on terror. People were outraged that we had total deficits of 3% of GDP when debt was already at a “dangerous” 30-40% of GDP.

We blew the lid off these concerns with the great financial crisis and ran total deficits of 6-9% of GDP in that 2009-2012 period. Then we got them down to a “normal” 3-4% when, just 5-10 years before, 3% was considered too high. Debt to GDP was settling in around 65-75% of GDP.

We again blew the lid off our concerns during Covid. Total deficits hit 15% of GDP and debt jumped to 100% of GDP. The new “normal”, acceptable deficit seems to be 4-5% and we are projecting raising it every year or so by a half percent until it’s 11.1% and debt is 185% of GDP by 2052.

Long before we hit 185% of GDP, I predict, we’ll get (a) a popular backlash and (b) a global market backlash. I’m more sure of (a) than (b), however.

My friend Les Rubin at Main Street Economics likes to remind everyone that our current debt burden is $369,000 per every single person in the United States today (adults and children both). If people really understood that, it would be politically unacceptable. Les is working on getting that message out and trying to do so in a non-partisan way which is one of the reasons I like and support his efforts.

Additionally, as explained above, most of that debt and growth in debt is due to the mandatory spending that Congress has voted on and locked into law. It takes a larger portion of the projected budgets available each year. Add to that growing interest rate payments which eat more of the discretionary budget as well. That all leaves less for the politicians to fight over, and hence means more intense fights.

We see that political fight today over the debt ceiling. We will continue to bump into that ceiling under these projections, because our debt will be rising ever more quickly. So, the political fights we are watching in the news today will become more frequent, not less, in the coming years.

Public interest in this topic fluctuates, but it will come back, and I suspect there will be some deals done in DC to reform some of the mandatory spending programs, reduce some spending, raise some taxes,q and improve the financial situation.

That there will be a global market backlash is the standard prediction most economists make, but I’m not 100% sure about it for the USA. The US is the largest and most important economy on the earth. If a smaller economy or a less developed economy hit debt of 80% or 100% of GDP, you’d start to see investors get nervous. You’d see investment flows into the country slow. That slowing would make investment funds more scarce and hence interest rates (the price of funds) would rise, reflecting the scarcity which reflects underlying concerns about repayment and financial viability.

Japanese government debt is currently about 260% of GDP. It jumped during Covid as well, but was already at 230% of GDP in 2019 (see Trading Economics: https://tradingeconomics.com/japan/government-debt-to-gdp ) and interest rates are still basically zero.

Japan is relevant because it’s also a large and important economy. Despite it’s high debt, it’s still viewed as creditworthy, and hence suggests the same might be true of the USA. (Don’t tell our politicians…I don’t want to encourage them!).

Also, it was already at 230% of GDP in 2019 and clearly investors were willing to lend more to them, allowing them to hit 260% today.

Of course, to get these benefits, investor have to believe that we will repay. They believe Japan will, and so they are willing to lend. If we default on any part of our debt, our credit rating will fall – as it did in 2011 during the last debt ceiling battle and default threat – and that will indeed require a higher interest rate.

The Economic Problems

The problem with large governments and massively high and rising government spending is, yes, financial, but more importantly it is economic ,and those problems are really shown in the GDP graphs.

Because government has no revenue of its own, higher spending means higher tax payments (today or tomorrow). Even if we agree with 100% of the spending, the removal of funds from private hands via taxes necessarily leaves private people with less to spend and allocate themselves.

Diminishing returns tell us that the more you do of a single thing, the less and less you benefit. That first glass of water quenches your thirst. The second in a row, less so. The third in a row, even less. And that’s why at some point you stop and do something else (eat, or, if you’re a kid, go back out and play).

The same is true of government spending. Pretty much everyone agrees we need to pay some taxes to get minimum government services (laws, police, military, courts, roads and so on). Most people would even agree on a level beyond that including a basic social safety net.

But, as we pile on more and more spending, each marginal gain is smaller and each marginal cost (in terms of diverting private resources) is larger. And that is part of the lower GDP story. Another part – although not totally independent – is the growth of regulation and the administrative state in every aspect of economic life. Again, most people agree we need some regulation, but there’s a limit before it really starts to slow things down and become counterproductive. The projected slowdown suggests we ran right past that limit.

All this means that, to some extent, it is a policy choice to have low GDP growth. It’s not a tradeoff for a cleaner environment or a more just society, it simply a result of bloated government financially and regulatorily.

These Trends Will be Reversed

Like I said before, I can’t believe this is really the long-term path. True, I don’t see any signs today that we’ll fix it, but I do know it is fixable.

We could easily scale back, re-evaluate and roll back some regulation, some state agencies, and that would also allow government to do better the things we care deeply about. Right now, government doesn’t seem to be doing anything well and that’s a problem.

People will not long accept a $300,000 debt bill per person. Political resistance will grow. We will all get sick of the annual debt ceiling theatrics. There will be more and more groups proposing debt limits, balanced budget amendments and the like.

It’s not a left or right issue even. With a shrinking pie, neither side will have the funds they want to achieve the ends they want.

And, if the debt to GDP continues in this direction, other countries will begin to move off the USD. They will move off US Treasuries as the world’s “risk free” asset, the foundation of global finance. When that happens, the cost of these policies will rise rapidly.

The Fed has raised interest rates and will hold them high for the coming year, at least. Even if they hold them at 5% this year, 4% next year and so on, that alone will add a lot to the growth of the interest payments on debt and squeeze the budget further. I suspect debt, interest rates, inflation and taxes will all be major topics in next year’s US Presidential election.

The wealthy can bear the higher interest rates and move their money to avoid taxes. The wealthy elite also get most of the government payouts from corporate subsidies to research grants at top universities where professors start at $300,000 a year.

The poor bear the biggest costs of all of this. They suffer from inflation and stagnant wages the most. Those without jobs are on fixed incomes and get decimated by inflation. Those with jobs pay taxes sooner and for more of their lives because they forego college in order to work and put food on the table. Higher interest rates means they can’t buy the houses and can’t afford the cars they want. And they are the first to lose their jobs as the economy slows. So, on a personal level, I believe there’s also a moral imperative to getting this fixed.

I never thought US debt-to-GDP would get this high. I never though we would accept 3-5% deficits with such non-chalance. But at some point reality must set in. Let’s hope it does sooner rather than later, and doesn’t require a crisis to get us there.

[1] Technically there’s a fourth option: reduce other spending by $10. We’ll ignore that because what we really have in mind is the net change in government spending.

[2] Or print money, but we’re focusing on borrowing in this discussion.

[3] Here’s the link for anyone interested: https://www.cbo.gov/publication/57971