There are two things I want to touch on that are concerning for me.

The first is the potential economic implication of what happened in England. England’s recent experience gives some cause for global economic concern. It’s a sign that many major economies are skating on thin economic ice these days and England revealed the ice might be thinner than we like.

The second is Japan. The Japanese intervened in foreign exchange markets to prop up their currency for the first time in since 1998. They intervened last month, which raised some eyebrows. But it seems they intervened again this month. This is now becoming a more dangerous sign than I think people realize. [Japan will be discussed in Part II.]

“If you should go skating on the thin ice of modern life…”[1]

Poor Liz Truss. I actually felt sorry for her.

Britain exited from the European Union – “Brexit” – to throw off the regulatory and bureaucratic chains of Brussels. The Brits had plans to simplify life, secure free-trade agreements with the US, and build a new British economy that would be better and stronger than the old. None of that happened.

The break from the EU dragged on longer than expected. The US never signed a free trade agreement. Then Covid struck. Talk about a string of bad luck.

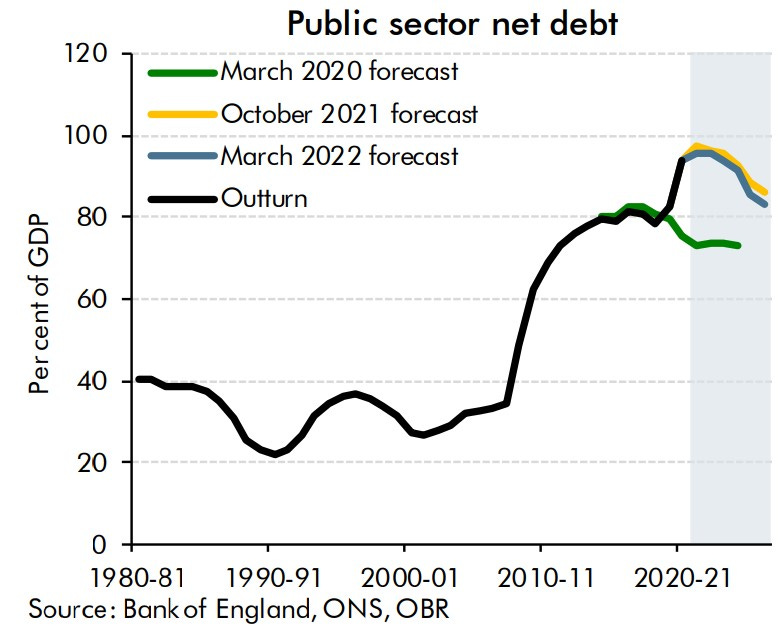

Like most countries during Covid, the British government went for broke to keep the economy from collapsing. The problem was that the government had already run debt-to-GDP up to the highest levels in 30-40 years to stave off the Great Financial Recession (GFC) of 2008.

The graph below – from the UK’s budget office[2] – shows that during and following the GFC, the UK ran government debt-to-GDP up from its relatively stable historical level of 40% to 80%.

Along came Covid and the government pushed it up to nearly 100% of GDP. That’s high and potentially problematic, but in bounds with, say, the United States.

Here’s the US graph…. It looks similar.

Our historical debt-to-GDP was around 60%, then up to 100% during the GFC and finally to 120% during Covid[3].

What conclusion(s) should we draw from that similarity?

Well, the first conclusion that everyone seems to have been drawing ex ante, that is, before the British mini-crisis, was that the British situation is not too bad. The US is worse. The EU overall is about the same as the UK. Relax England. Don’t worry. We’re all there too. You’re a developed economy, relax.

Then Liz Truss stepped in. She shook the Queen’s hand as new Prime Minister. The next day the Queen died. The next two weeks were all about the Queen. The country was mourning and no one – at least internationally – was watching what was happening politically and economically. All eyes were on the royal family.

Finally, the Truss Government began moving past the Queen’s passing and the Truss Government could finally come out and tell us all what they were planning: some minor tax cuts and increased government spending.

Markets blew up and started dumping British debt. … What?!

The tax cuts were not much but, honestly, the whole thing didn’t make sense. A pro-market government – like Truss claimed to be establishing – might argue for cutting taxes to return money to the people who can allocate it more efficiently than the government. That would then lead to growth and so on. The idea would have been: Get the government out of the way, let the private sector rule and everything will be fine.

But you don’t then combine the tax cuts with more government spending and stimulus. When you do that, no one hears “unleash the markets and efficiency”. We all hear that the government wants to cut taxes and increase spending to boost the economy. There’s nothing “free market” about that and it doesn’t make financial sense.

And then there’s inflation. More stimulus pours gas on the inflation fire. Running up higher debts at a time when the Bank of England is raising rates also means every dollar (actually, pound) spent will just be a bigger burden and cost the taxpayers more because the interest on each unit of debt is higher and higher.

Everyone started to drop British government debt, forcing their rates to spike even more. And those rate spikes, on top of the rate hikes from the Bank of England, shook the fragile foundations of pension funds in England that relied on low and stable rates. The Bank of England had to engage in bond purchases with these funds at a level it hadn’t done since the GFC. And, all in all, things went to hell in a handbasket, as they say.

Truss is gone and these policies have been cancelled. Things have stabilized. But after that unexpected roller coaster ride, we all sat a bit wide-eyed, half in disbelief, and otherwise tried to make sense of it all.

If the ex ante interpretation was that they look like the US, so they’ll be fine, then the ex post interpretation is that they look like us and therefore it can happen here too. That makes us all very nervous.

“…don’t be surprised when a crack in the ice appears under your feet.”

There is a real sense in which high inflation and these debt crises are signs of cracks forming in the thin economic ice on which we all skate today.

Economies can take a lot, but eventually they break if you really bend them too far. England showed that.

Commentators around the world were saying things like, “It was shocking to suddenly see the British economy being treated like an EM (emerging market) in world markets”. By that they meant that when EM’s hit certain points – and traditionally debt-to-GDP of 80-100% would be such a point – they become fragile as if they are balancing on a blade where any small tremble can cause them to tumble off one side or the other.

The UK debt market isn’t supposed to behave like that. It did. And that scared us. And it should.

The thin ice is that we have pushed government spending, financed largely by debt and printing money, to the limit. There isn’t any more room to push. And if you are in a country where inflation is out of control, the economy is faltering, your currency is falling, and your central bank is raising rates rapidly, then it is painful. The temptation to help with some more government money is strong. But it is the wrong medicine. It’s like drinking alcohol to get rid of a hangover. You can do it. Maybe you can even do it a few mornings in a row, but eventually it just makes things worse and a whole host of other problems start to materialize as well. That’s where we are economic-policy-wise in most countries today.

[1] Sorry. It’s England and thin ice. I couldn’t help but think of these Roger Waters lyrics.

[2] Link: https://obr.uk/docs/dlm_uploads/Exec-sum.pdf . This graph is on page 13.

[3] Technicians can debate the exact numbers and measures, so I’m ballparking everything here. These are official numbers, you can look them up and read how they are calculated. The general story, magnitudes and direction are what really matter. Here’s my FRED chart: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=VgBe