Last week the US Fed had its annual Jackson Hole meeting of the intellectuals of monetary policy. The news focused on Chair Powell’s comments that the Fed will stick to its policy, continue to raise and then maintain higher interest rates until inflation is truly vanquished. That apparently popped the delusional bubble around stock market investors who hoped that the Fed would ease up. And now, all eyes are watching our weekly US data again to see what happens next.

In the meantime, in a galaxy – err island – not too far (far) away, the Bank of England said it expects UK inflation to continue to rise all year long to 13% or more into next year! Yet the Bank of England has been raising rates too!

The Curious Case of England

The Bank of England issues quarterly inflation reports. In August they wrote[1] that (a) their inflation target is still 2%, (b) inflation is now about 9.4%, (c) they voted to raise rates by 0.5% again in August, putting their policy rate now to 1.75%, and that (d) “CPI inflation is expected to rise more than forecast … from 9.4% in June to just over 13% in 2022 Q4, and to remain at very elevated levels throughout much of 2023, before falling to the 2% target two years ahead.”

The same report said, “GDP growth in the United Kingdom is slowing”, yet “[t]he labour market has remained tight, with the unemployment rate at 3.8% in the three months to May and vacancies at historically high levels.”

I don’t understand this. Seriously, some days I feel like I do not understand the economic world today at all. It’s part of why I launched this column. Sort of like therapy for an economist.

What I Don’t Understand

Let’s just focus on one or two things I don’t understand.

First, if you removed reference to the UK and spelled labor without a “u”, this describes the United States: slower growth, crazy low unemployment and positive inflation. It also happens to describe several other countries which I’ll get to below. The difference is that, in the US, we think inflation peaked or is at least in the process of peaking now. The other countries think it’s still rising. Why? What’s different?

Second, and this is an issue with every major central bank today, the English monetary authorities claim they have an inflation target of 2% but current inflation is 9.4% and rising this year alone to 13%! Yet they write this: “The [monetary policy committee’s] remit is clear that the inflation target applies at all times, reflecting the primacy of price stability in the UK monetary policy framework.” And, “[m]onetary policy is also acting to ensure that longer-term inflation expectations are anchored at the 2% target.” What are they doing to “ensure” that? Raising interest rates a half point to 1.75 when inflation is 9.4%? Are they “ensuring” their policy by keeping real interest rates (the nominal, or actual, rate minus inflation) negative at – 7.65% ?!

They, like the US Fed, Bank of Canada, European Central Bank and others are saying they are fighting inflation and doing everything possible and that interest rates are their key policy variable, yet real interest rates are negative in all the countries. This makes no sense.

And they are saying that “the key” is to anchor long-term inflation expectations at 2%. That’s why they state over and over that they all still have their inflation targets at about 2%. But inflation is around 9% and they aren’t raising rates quickly and the UK expects 13% going in to next year. So in what meaningful sense do they have a target?

The Mystery

The real mystery here is what drives and controls inflation. And, I think we don’t know anymore. This has been a long time coming and I don’t want to be an alarmist, but we don’t know.

Professor John Cochrane just had a great piece in the Wall Street Journal entitled “Nobody Knows How Interest Rates Affect Inflation[2]” (August 24, 2022). At the heart of this is the fact that nobody knows what determines inflation anymore. Hence, nobody knows how interest rates affect it either.

John is well aware of this problem because he’s been writing about it since the 1990s and has a new book on the topic, The Fiscal Theory of the Price Level, that comes out this fall. He has more information and drafts of the book on his private site[3]. It’s pretty technical and will be studied in PhD programs for years.

He’s a top academic in this field and began seeing years ago that our traditional models were all coming apart at the seams. Other top academics have been chipping away at this for years as well and it got my deep interest in the last 10 years or so.

Again, this is not to raise alarms although it’s admittedly disturbing that our best and brightest minds in this field aren’t sure anymore. And it’s more disturbing that our central bankers don’t know.

The good news is that either the new models are right and the central banks don’t have to raise interest rates as much as we thought, yet inflation will fall again. Or the old models are right and we don’t have to raise interest rates as much as we thought, yet inflation will fall again. Or, there are some recent – not new anymore but still not truly old – models that say we should raise interest rates a lot. If they are right, we can still raise rates and kill inflation. So, whoever is right, we’ll eventually get there. But how and when is the question.

And, yes, it should infuriate you as it does me that we have to go through this experiment which is horribly painful for everyone, especially those least able to bear higher prices and recessions, namely those in lower income categories and lower income countries.

Theories of Various Vintage

In a nutshell, the “old theory” says it’s all the money supply. Print money faster than GDP growth and you are pouring money in faster than people are producing things. As a result, people feel flush with cash, run out to buy things but the economy can’t produce enough things fast enough so the prices of those things gets pushed up. That’s inflation. The way to end it is to print less money.

That is both the old theory and the way we all essentially explain it in our classrooms, textbooks and newspaper articles. Some of us, John Cochrane is an example, are trying to be honest and describe it in terms of newer theory, but it’s tough.

“Recent theory” says that the interest rate rules all. This was the dominant theory from about the mid 1990s until about 2015. This theory is embedded in all the models central banks use today. It’s a belief that there exists an interest rate that has a natural rate corresponding to natural unemployment and natural inflation in an economy. Around that, inflation fluctuates up and down essentially with a supply and demand story like I told before but with one twist: when interest rates are low, people can get more cash easily and demand more goods than the economy produces and this causes inflation.

You can see that the core story is essentially the same. The source of the cash is just different. In the old theory the Fed printed too much cash. In the recent theory, the Fed simply made the cash cheap to obtain, as credit.

“Modern theory” says that a dollar – a unit of national currency – is only as valuable as the government that issues it, kind of like a stock is only as valuable as the company in which it’s an ownership share. The parallels aren’t too off actually since dollars are just a special kind of ownership in the US government. Also, like stock prices, there’s a fundamental value and a lot of expectations and perception causing noise around those fundamentals. For stocks, value is based on the expected present value of future corporate earnings. For a government’s currency, value is based on the expected present value of future primary government budget surpluses. And interest rates in this world control inflation expectations a lot and that’s why the Fed’s ability to anchor expectations remains critical.

A simple reading is that the “old theory” says too much money causes inflation, “recent theory” that too low an interest rate causes inflation, and “modern theory” that expected future deficits and debt cause it. We can’t test the various theories, but looking at the world through the various lenses gives some insight into the world and the confusion today.

An Old Theory Perspective: Money in Australia, Canada, the UK and US

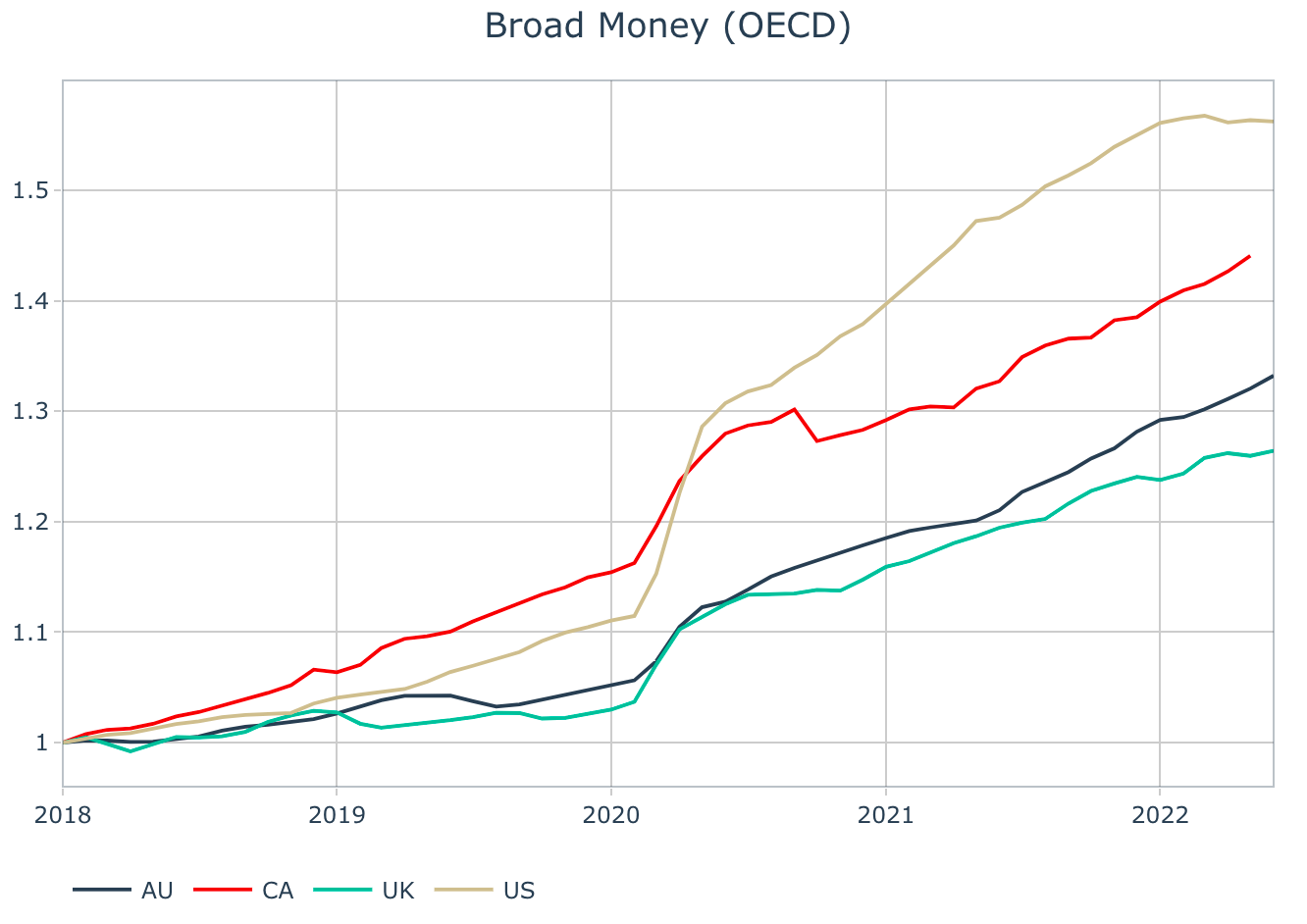

So, here’s the data on the money supply in these countries.

I use broad money which is a loose category. The graph here is an index set to 1 in 2018, so a rise from 1 to 1.1 means a 10% increase since 2018, for example.

This picture is clear. Canada (red line) was printing money at the fastest rate prior to Covid, but during the Covid crisis the US (gold line) increased the money supply the most and, more importantly, continued to increase it way beyond what the other countries did. Hands down we’d expect that – all else equal – the US would have the worst inflation and likely by a long shot. Second might be Canada. The UK (green) and Australia (dark blue) would likely be tied for last.

A Recent Theory Perspective: Interest Rates in Australia, Canada, the UK and US

Next we look at overnight interbank interest rates. These are some of the lowest rates in a country and are most directly influenced by the central bank.

All the countries put interest rates near zero during Covid but the UK looks like it had the lowest level. Again, often it’s the change that matters more than the level. In that regard, again, the US and Canada lowered rates the most because they had the highest rates prior to the crisis. We then see the UK raised rates earliest, then Canada and the US raised them more and apparently faster, then Australia raised them equally as fast but later than the others.

Overall, this graph is mixed. The UK had the lowest rates. If that’s it, then they should have higher inflation. The US and Canada clearly lowered them the most. If that’s it, then they should have higher inflation. And there’s no real prediction for Australia.

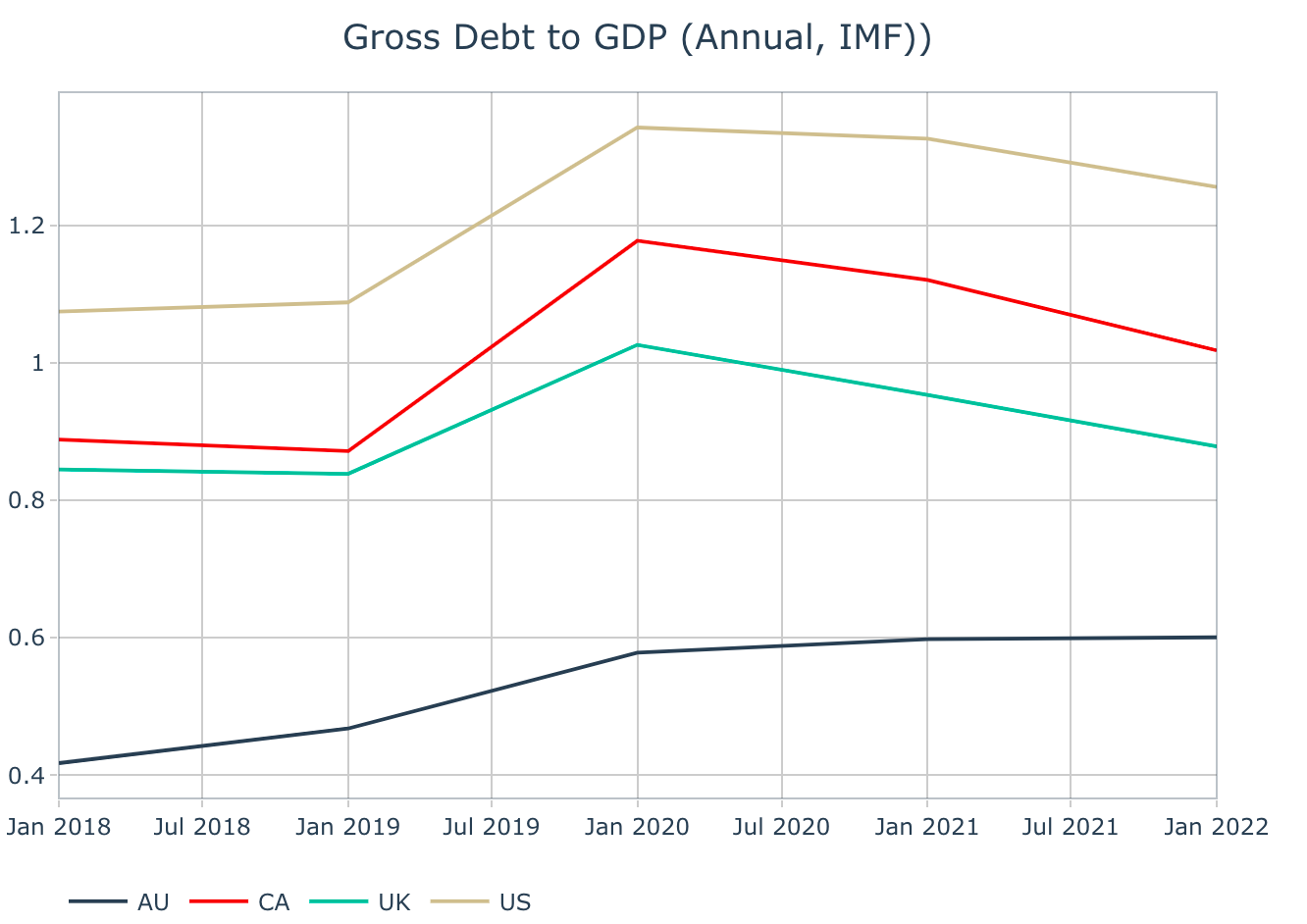

A Modern Perspective: Debts and Deficits in Australia, Canada, the UK and US

Next let’s look at debts- and deficits-to-GDP. A simple “modern theory” thought is that a country with higher debt to GDP and that ran higher deficits in recent years should have more inflation today (assuming markets expect future deficits to be worse too).

Clearly since 2018, the US had both the highest debt to GDP of all the countries. And just looking at the graph, that increased the most in Canada with the US second or tied with the UK for second in terms of the rate of increase during Covid.

So, based on this, all else equal, for the same experience, we’d guess inflation will be highest in the US if the level matters most or Canada if the increase matters most. Then third, maybe, the UK and lastly Australia for sure.

But the “modern theory” isn’t just about debts, it’s about government deficits. And we don’t have expected future primary deficits, which is technically what they theory says matters. But, all else equal, we’d think that worse deficits today might signal the same for tomorrow and be an indicator. So, worse deficits (as a percent of GDP) ought to be potentially more inflationary.

The government primary balances generally move together but the US does stand a bit out from the pack. Here we see the US was the most below zero (worst deficit) prior to Covid, dropped the lowest (you see the golden trough poking out below the bottom) and then improved, but dropped again in a big way in 2021 and again at the end of the graph. The last drop shouldn’t affect inflation today. There’s a lag. So, we’ll ignore it for our current purposes, but it doesn’t bode well for future inflation.

Clearly this perspective suggests that the US should have the worst inflation of the group. The message isn’t clear for the rest of them in terms of who might have relatively more inflation than the other, but it is clear that we’d expect all of them to experience some inflation for sure.

Inflation

First, a quick summary: Based on money, the US should clearly have the highest inflation and it should be more persistent since we printed money faster and longer than the others. Based on interest rates, it’s very mixed but possibly England “wins” if the lowest interest rates drives inflation and otherwise the US or Canada would be the “winner” since they cut interest rates the most. Finally, based on debts and deficits, the US looks again to “lead” the pack with the worst debt-to-GDP and the worst deficit-to-GDP in both level and rates of growth. On average, across all the variables, we’d expect the US to have the worst inflation of the pack.

Great, the US has the worst inflation. So now which theory is driving it?

This is the problem economists face today. We have three theories or stories of what drives inflation and the US committed all three crimes, so to say. The very end of the data captures that the UK hit 9% and now exceeds the US.

The next months should tell us more, but they might have more to do with who has been raising rates more and faster. Again, the US and Canada seem to be in the lead.

But what if UK inflation really hits 13%? What does that tell us about (a) what drove inflation and (b) what fights inflation? To be sure I’ll be looking soon at the Euro area versus the UK since they are facing similar energy shocks from the war in Ukraine which might be one explanation for continued increasing UK inflation.

One mystery here is why Australia looks like the others at all though. They did the least in every category.

Cochrane is right. We don’t know how interest rates affect inflation.

One crazy thing is clear though: The central banks, who all claim to follow the “recent theory”, aren’t acting like they really follow it. If they were really following it, they would be raising interest rates much higher and much faster. So, they don’t fully know either.

There are many, many reasons for this. It’s not just academics with their heads up their ivory towers. The entire structure of money and banking has changed and with it the connection between interest rates and money and inflation.

I’ll keep digging into these topics. And special thanks again to my research partner Jack French who is digging with me. He provided all the graphs in this article. Together we’ll be looking very closely at all this data and much more data for many more countries all the way back to 1970 for an academic paper we’re writing. You’ll be sure to see more pieces of the puzzle as we find them.

I hope this gives you a sense of what economists are looking at and why we are all still scratching our heads these days.

Thank you for reading.

[1] Bank of England’s August Monetary Policy Report. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy-report/2022/august-2022#report-august

[2] https://www.wsj.com/articles/nobody-knows-how-interest-rates-affect-inflation-unstable-stable-seal-pendulum-1970s-spirals-expectations-federal-reserve-11661368265?st=s6cbt5eehe2awpk&reflink=desktopwebshare_permalink . He dives deeper into the topic, adding pictures on his private blog: https://johnhcochrane.blogspot.com/2022/08/wsj-inflation-stability-oped-with.html

[3] https://www.johnhcochrane.com/research-all/the-fiscal-theory-of-the-price-level-1

Thanks for the comment. Yes, part of the argument in favor of developing the Fiscal Theory of the Price Level is the view that monetarists view credit created by the commercial banking system as inflationary and yet the modern empirical evidence from the 2008 crisis suggests this isn’t the case…. I listened to Mehrling’s interviews on Bloomberg Odd Lots and read material from his faculty site. I like his thinking and plan to dive into it a bit more. He’s much more on the technical, banking practitioner side. … the non-pity for us macroeconomists is that there’s always more to learn and that keeps things interesting! Thanks for reading!!!

Pity the macroeconomist...The main problem(s) with the Cochrane view of inflation is that his theory totally ignores credit creation by the commercial banking system, including the Eurodollar system, which is a huge driver of 'money' creation. A related issue is that for the US, one needs to focus on the impact of the global dollar system, rather than just on US-centric variables (like US broad money). At the end of the day, the Fed is effectively the world's central bank (and lender of last resort) - see Perry Mehrling's work.