Global Economics Q&A: Which Interest Rates?

After reading “How High Should Interest Rates Be?” several people asked me: Which rate are you talking about? Do you really mean the federal funds rate or do you mean commercial rates?

This is always a problem for economists. We talk about “the interest rate” but of course there are many interest rates in an economy. So let me be more clear.

When I wrote that “As the Federal Reserve (FED) raises interest rates, people have been asking how high interest rates will go. The answer is that they will go up a lot this year and then settle but my best guess at this point is that they’ll be 6-10% this year and 4-6% next year, if all goes according to plan.” YES, I mean the federal funds rate. YES, I mean commercial rates.

The FED’s Federal Funds Rate

I do expect that the FED will have to raise the federal funds rate substantially. They might or might not do it right away, but eventually they will have to. The nominal interest rate is the real rate plus (expected) inflation. If we think inflation is even 5% on average this year – and it’s looking more like 8-10% this year – then nominal interest rates must be that amount plus something. So that gets us to 6% for the federal funds rate for sure.

Furthermore, the operating assumption for policy over the last, say, 20 years and especially since the 2007/2008 crisis has been that the FED must raise interest rates faster than inflation in order to stave off inflation. This is called “the Taylor principle” because it’s tied to the Taylor rule which is the interest rate rule many policy makers follow for guidance on the federal funds rate itself.

The Taylor principle says that if inflation rises 1%, then the federal funds rate need to rise more than 1%. That forces the real interest rate up encouraging everyone to save more and consume less today. That in turn slows demand today which cools the economy down, ultimately slowing inflation. So, if the FED follows this at all, then the federal funds rate should already be 6-8% today depending on which measure of inflation the FED looks at.

Commercial Rates

The easiest way to think about different interest rates is to think about risk. Despite all our complaints about the US government’s finances, global market participants still consider the US government to be the most sound financial institution in the world. The US FED is also essentially considered a riskless institution. So whatever interest rate the US government and its various agencies – like the FED – charge, it’ll generally be lower than other market rates because it’ll be considered nearly riskless.

The reason those are considered so sound is that, unlike any other institution, government institutions are fundamentally backed by the American people and the American economy. And, as long as people in markets believe the US economy is fundamentally sound, can improve, can overcome any current hurdles, etc., then they believe the US government can always pay its bills too. In the end, the government’s debt is its people’s debt because the only way a government can ultimately get money to pay debts is by getting it from its own citizens in the form of taxes[1].

Something riskier like personal loans will have higher interest rates than FED rates. But still, banks vet their clients. You have to fill out a loan application, show you have funds to repay, etc. So these are riskier than the government but not as risky as, say, credit card loans. With credit cards, banks are providing essentially immediate credit at any time, so those rates will be higher still.

Finally, as a general rule, there’s a trade off between short term loans and long term loans. In some ways long term loans are more reliable because we borrow for bigger ticket items like homes and cars and go through more vetting which lowers the risk some. But over a long time horizon a lot more can happen so there’s a little more risk from that perspective. In general, rates are high for super short term loans (like credit cards) because there’s a cost to getting that money fast and because there’s less time to review a person’s finances each time they charge on their credit card. Rates then drop a lot for loans that might be 6-12 months or even 2 years in length. From there rates are higher the longer the horizon.

A 15-year mortgage loan and a 48 month commercial loan for a car are both about 4-5% today, for example. A 24 month personal finance loan, which is a little riskier, is about 10% today. And credit card interest rates are around 14-15% today.

So, Which Interest Rate?

I think FED rates will have to get up to the 5% range for sure this year. And if the FED really follows the Taylor rule it prints on its own website as a benchmark, then it’ll have to raise that rate more than 5%.

The real question is whether the Taylor principle is right. If it is, the FED must raise raises higher and faster than inflation to reduce inflation. If the FED is initially timid – as it has been thus far – then inflation will continue to rise and stay high and the FED will have to raise rates even more later this year to get inflation under control. That would mean rates don’t rise as fast now, but by, say, summer, the FED will have to raise rates dramatically.

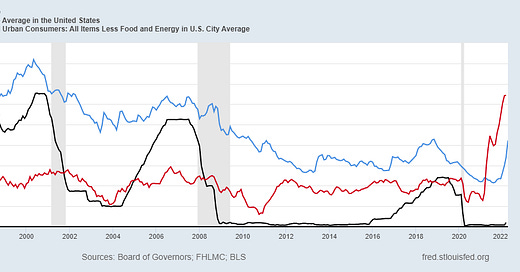

The other commercial rates will go higher too. Over the last 30 years, for example, 15-year mortgage rates have been 2-3 times inflation. So with inflation at 8%, mortgage rates should be 16-24%. They are not. They are 4-5% which tells us that either the markets don’t really believe the 8% will last or they just haven’t caught up yet and will skyrocket. Or something in between. Currently I think it’s something in between. But the longer the FED fails to get inflation under control, the more these markets will adjust to higher expected inflation and we’ll see them rise dramatically.

Here's a graph of these rates and inflation over the last 30 years. It’s from the FRED database again. A link to it is below in case anyone wants the graph or the data behind it.

FRED graph: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/fredgraph.png?g=OGcD

It’s the black line, the federal funds rate, that is the anomaly. It’s too low. And that will change soon this year.

[1] In the short run of course the government can borrow from someone else or even print money. But ultimately the government’s ability to pay its debts is dependent on its ability to get money from its citizens.