How High Should Interest Rates Be?

As the Federal Reserve (FED) raises interest rates, people have been asking how high interest rates will go. The answer is that they will go up a lot this year and then settle but my best guess at this point is that they’ll be 6-10% this year and 4-6% next year, if all goes according to plan.

Which Interest Rate?

Which interest rate(s) do I mean? Normally the market rates like US treasury rates and the FED’s federal funds rate would move together. Today they do not.

I will address this at further length elsewhere. For now, we’ll break the answer into market rates and policy rates.

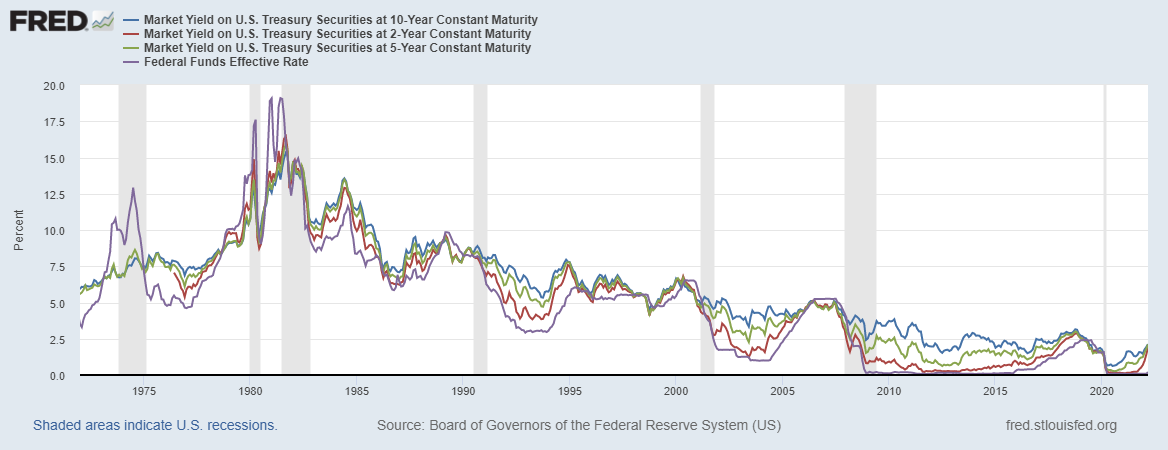

For market rates we can think of the market rates on US Treasuries. They move together over time although at any point they can differ some with longer term rates usually being higher. Here’s a link to the graphs and data below (link: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=OiZX ).

For the policy rate, we’ll definitely think of the FED’s federal funds rate widely considered their key policy rate although that’s a topic we’ll also have to address at length in another column.

Normally the FED’s federal funds rate moves with these market rates as seen here. The FED’s rate is in purple. All the others are the same as in the first graph.

It’s clear they move together with the FED’s rate usually being the lowest. But if you zoom in to the end of the graph, you can see that they have recently diverged.

As a result, we have to discuss them a bit separately. And, to get ahead a little bit, that’s why everyone feels the FED has been slow to raise rates since about summer if it was proactive and fall for sure.

Market Rates

The nominal interest rate is the real interest rate plus expected inflation. Since real interest rates are currently around zero, this says that nominal interest rates should be the same as expected inflation, maybe plus a little more (like a .5 point to account for “real interest rates”).

This can be seen historically (link to graph and data: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=Oj0w ).

Market rates (and the FED’s rate) generally move together during normal times and the inflation rate (bright green line) is usually lower than interest rates. We can see at the end that inflation is rising much faster than market rates (and FED rates) since the Covid crisis, starting in 2020.

Since it is likely that inflation will be 6-10% this year, market rates should be around 6-10% as well, maybe plus a half point to account for real rates. If inflation comes down this year, then we should be expecting inflation to be 2-6% next year.

Beyond that I don’t think we can say much today. If the FED does its job and there aren’t more total surprises like Covid, Ukraine, etc., then we’ll be near the FED’s long-run inflation target of 2.5% about 2 years from now. When and if that happens, interest rates should be 2-3% and maybe a little higher depending on real interest rates.

Policy Rates

The FED’s federal funds rate has traditionally been considered the key policy rate the FED uses to conduct monetary policy.

What economists think the FED should be doing with the policy rate differs according to which economic school of thought they ascribe. The schools are: traditional old-school monetary theory, modern monetary theory, and cutting edge monetary theory.

School One: Traditional Monetary Theory

The traditional school is sometimes call “monetarism” and basically says that inflation comes from printing too much money relative to GDP growth. This is linked to the old adage that “inflation is too many dollars chasing too few goods”. In this view, interest rates are market determined and hence they will be what I mentioned above: 6-10% this year, 2-6% next year and 2-3% thereafter if policy succeeds.

Now, traditional thinking says the FED should slow inflation by lowering the growth rate of money. When that happens, it will likely cause interest rates to spike up because it suddenly lowers liquidity in the markets. So, one might also expect interest rates to rise beyond 10% in the short run as policy makers put the brakes on money printing. You can see that happen in the last graph in the early 80’s when the FED dramatically reduced the growth rate of money in an effort to stop runaway inflation. The result was a series of spikes in the federal funds rate (purple line).

Let’s say then that interest rates should pop up to 10-15% in the coming months according to this view, then follow the “Market Rates” path I described above. Maybe everything I argued above follows 6 months later than I described it, but if successful, inflation could fall faster. So we’d see a higher spike initially but a faster drop than I claimed above.

Traditional theory dominated until the 1990s. It’s still very popular. It is the way monetary theory is presented in all undergraduate economics textbooks even to this day. And as such, holds a lot of sway and has strong intuitive appeal for all economists, including me.

School Two: Modern Monetary Theory

In 1993, Professor John Taylor published an article showing that monetary policy can be described historically in terms of interest rates instead of the quantity of money. And then argued that one could describe FED policy as essentially following an interest rate rule that raises interest rates when inflation rises above the FED’s target inflation and falls when inflation is below the target. Likewise, interest rates rise when GDP is above what is considered GDP’s potential (or “full employment” level) and fall when GDP is below its potential. Such a rule is called a “Taylor Rule” after it’s now famous inventor.

The new monetary models that emerged in the 1990s, now called “New Keynesian” models, all relied heavily on Taylor-type interest rate rules and it became the key tool to use at central banks around the world. Essentially at a policy meeting, decision makers commonly use it as a benchmark against which to evaluate their actual policy choices.

The US Atlanta FED even has a Taylor Rule tool online where you can generate what the Taylor Rule says interest rates should be today based on the FED’s own data and parameterizations. Doing that today (April 15, 2022) shows that, according to the Taylor Rule, the FED’s federal funds rate for Q1 should be somewhere in the 7 – 7.5% range even though the federal funds rate for Q1 was only .12.

To check the Taylor Rule yourself, go here (click the “chart” button, then scroll down to see the graph or download the data): https://www.atlantafed.org/cqer/research/taylor-rule .

The blue line shows the Taylor rule calculated the way Taylor did in 1993. The purple line shows the actual federal funds rate. Whatever your opinion, we’ve been way off the Taylor Rule since the start of Covid. Many people believe that the federal funds rate (purple) being below the Taylor Rule (blue) in the 2001 to 2007 period reveals the “easy money” period that led to the financial crash in 2007/2008.

So based on the Taylor rule, interest rates should be around 7-8% today, maybe up to 10% based on the latest CPI report with 8.5% inflation. Again, the FED is behind in doing its job and this is why many economists are predicting dramatic rate hikes this year.

School Three: Cutting Edge Thinking

This isn’t a single school yet. But there are a lot of problems with the “New Keynesian” models of the late 1990s to current times. There are a number of alternative versions of these models now. Some use Taylor-type rules, some don’t. Fundamentally, in my opinion, we do not really know what determines inflation today. That’s a disturbing thing to say as a macroeconomist and part of the reason I started writing this Substack column. I am exploring this topic, expect to continue to do so and will take readers along with me on the ride.

A leading thinker in the cutting edge of research is Professor John Cochrane of Stamford University. He’s developed a sound theoretical framework around a “Fiscal Theory of the Price Level” (FTPL) and hence “inflation” which is just the rise in the price level over time. This theory says that the value of money lies entirely on everyone’s belief in the fiscal soundness of the government which he captures as the expected present value of future government surpluses/deficits.

He's recently shown why the FED could have in mind a model where simply announcing lower inflation, and having everyone believe you, would lead to lower inflation without having to dramatically raise interest rates and cause a massive recession. His work is a little technical, but you can find it here and he’s a person I regularly follow (and I generally subscribe to his Fiscal Theory of the Price Level). https://johnhcochrane.blogspot.com/2022/04/is-fed-new-keynesian.html

So, if you believe that the FED is credible in announcing future lower inflation and that it will hit it’s 2.5% inflation target again in the coming years and if you believe that the fundamental long-term financial stability of the US government is actually fairly stable, then this view says that current inflation was a policy mistake, but will be easily rectified with some mild interest rate increases. Essentially the FED should set interest rates a little higher than their long-term level (around 3%) and the economy will adjust to that over the coming 12-24 months. (This is not necessarily Professor Cochrane’s claim, mind you, he just shows that this thinking is consistent with a version of current FED models and can be explained in terms of his FTPL framework.)

My View

I am sympathetic to Prof. Cochrane’s FTPL theory. This framework also allows for old school traditional thinking and has some room for Taylor Rules too, so it’s quite open. It’s more a new way of thinking about the world given modern financial institutions than it is a counter point of view although it does make some different and interesting theoretical predictions.

I also still have a hard time overturning traditional thinking and you’ll see more posts from me about the quantity of money. I think we are missing a lot today by ignoring it.

I will be exploring and explaining these various theories in upcoming articles. For now, based on all the above, and some basic gut intuition, I restate the claim I started with: my best guess at this point is that market and policy interest rates will be 6-10% this year and 4-6% next year, if all goes according to plan. I’ll add that I leave a small probability that things get much worse and they exceed 10% but it will be due to outside factors like the Ukraine war and supply disruptions. I hope that doesn’t happen.

No matter how you cut it, market interest rates will be much higher this year and that will slow economic growth. We will have a recession. And it will make life for every politician a living hell because the cost of US debt will rise rapidly as interest rates increase around the world.

* Special thanks for a former student who encouraged me to clarify which interest rates I’m looking at and to add some links so people can find that data themselves. It made this longer, but I think better. Thank you!