Recession Obsession

Are we in a recession yet? How about now? Now, now…how ‘bout now?

Everyone suddenly seems obsessed with a recession like kids in the back seat of the car – are we there yet?

For starters, does it matter when we officially call it a recession? I know it matters politically, but does it matter for anything else? Not really.

Now, let me be clear. I believe 100% that the US economy will enter a recession this year. I think it’ll take that turn around summer. But when it’s technically called a recession can be anytime this year. What matters is how we feel, how hard our lives get and how quickly we can return to normal.

If you do want to know the official announcement of our recessions though, in the USA the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) officially calls our recessions. You can find their explanations and announcements here: https://www.nber.org/research/business-cycle-dating

Two Quarters of GDP Decline!

Let’s get one thing out of the way at the beginning. Two quarters of negative GDP growth is not the definition of a recession. That it is the definition is a very popular misconception and you hear it all the time on TV. But it’s not true.

The reason it’s a popular – but wrong – view is that GDP slowing usually goes with unemployment rising. So, most of the time, if GDP really falls for two whole quarters (half a year!) then unemployment is rising too and things are looking pretty bleak. But economics actually worries a lot more about people’s actual wellbeing and that’s usually captured with unemployment.

Economic Definitions of Recessions in General

There isn’t a really good definition of a recession in economics that holds at all times and in all places. Generally speaking, we think of a recession as GDP falling significantly and unemployment rising significantly.

Conceptually for a recession, GDP should fall below the “full employment level of output” and unemployment should rise above the “natural rate of unemployment”. The two concepts are clearly related.

The Natural Rate of Unemployment

We think of a natural rate of unemployment as being the amount of unemployment that a well-running economy should naturally have. Kind of a tautology, I know.

In a healthy economy there should be churn as people search for jobs, change jobs, and so on. That’s technically the natural rate of unemployment.

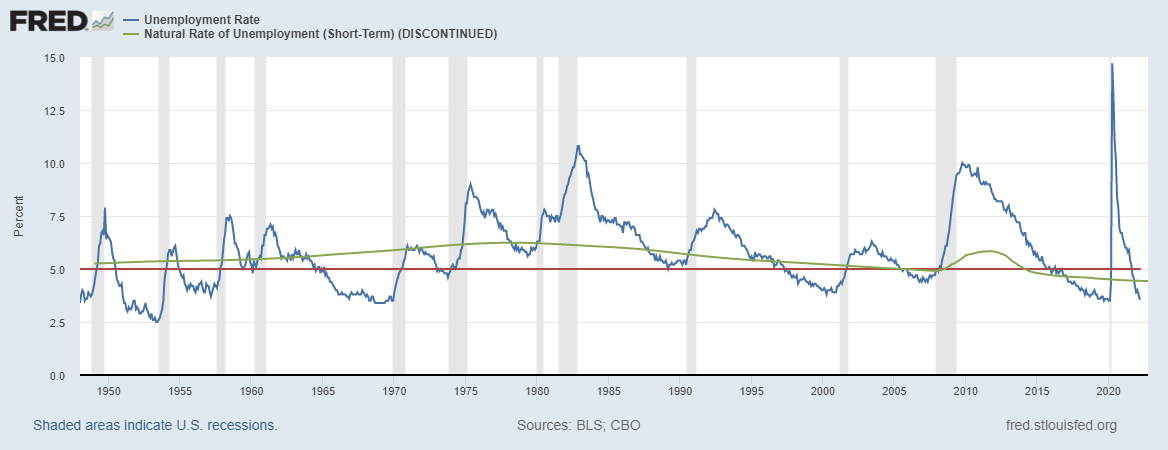

But what that number is isn’t set in stone. The natural rate differs across economies. In the USA we think it’s around 4-5% these days. In Europe it’s probably more like 7%. In Japan it was historically more like 2-3%. That also changes over time.

Many European countries have very restrictive labor laws so it’s hard to fire people. As a result, businesses are also slow to hire people because if they do and business slows, they will be in trouble. As a result of these laws and other factors, unemployment tends to be higher in Europe than in the USA.

Germany had unemployment persistently near 10% for years. Then around 2002-2003 they implemented labor market reforms, making their labor markets more flexible and their natural rate is probably much lower now. See the graph below.

The Japanese have moved the other way, unfortunately.

Historically, Japan had crazy low unemployment of 1-2% but their “economic model” ran out of steam by the 1990s and they’ve been struggling ever since. Their natural rate of unemployment looks like it rose for about 30 years but could be returning to its old low now. It’s hard to know. And that’s part of the problem.

The United States hasn’t gone through such a profound change in either direction. Nevertheless we always watch and wonder if our natural rate is higher or lower than we think it is. Those of you who are a little older may recall that after the 2008 financial recession everyone was talking about “the new normal” and explaining that unemployment will be higher permanently now. People should just learn to live with higher, potentially European-style, unemployment. That was wrong.

If you imagine 5% seems like the natural rate in the USA (red line below), it actually makes a lot of sense. The teams of analysts in the government always update their estimates of the natural rate (green line below), so you can see it actually rises and falls with unemployment . That’s an honest mistake in my opinion. Sure in the 1980s it looked like “normal unemployment” was higher, but at a deeper level it’s clear the US could and would have much lower unemployment again. So a different read on that data is that the 1970s and 80s were more abnormal than we realized at the time.

The natural rate probably does evolve over time for an economy. The problem is that it’s not exactly clear how and why and what drives it other than very clear changes like in the case of Germany.

Full Employment Output

Once you think of the natural rate of unemployment as being the basic churn of employment in a healthy economy, then the full employment level of output makes sense. It’s the output (GDP) that the healthy, well-functioning version of our economy should be producing.

The other name for this level of output is “potential GDP”. It turns out to be even harder to pin down in reality. But conceptually it’s clear: potential GDP is what the economy is capable of producing when running well and when that happens, unemployment will also be at its natural rate.

Recessions Again: Covid and Unemployment

Back to the topic at hand. When GDP is below potential for a meaningful period of time, then unemployment should also be above the natural rate and these together are a recession.

It’s so confusing today because the unemployment numbers are screwy. The unemployment rate in an economy is calculated as the number of people unemployed (i.e., actively looking for work) divided by the number of people in the labor force:

unemployment rate = (unemployed people)/(people in the labor force).

The strange thing that happened during Covid was that many people left the labor force. Let’s make up some easy numbers to show why this matters.

Suppose that the US has a population of 330 (million) people[1]. Out of that 330, if 63% are “in the labor force” then that means there are 208 people available to work. The other 122 people are “not in the labor force”. Those people are children, retired people, students, and other people choosing not to work for various reasons.

Pre-Covid, out of the 208 people available to work, about 200 were employed and 8 were unemployed[2]. The unemployment rate was about 8/208 = 0.038 or 3.8% (actually it was 3.6% but I’m rounding to keep the numbers easy).

So now Covid hits and about 4% of the people working decide not to work. 4% of 208 is about 8 people. So if 8 people leave the labor force, that will automatically cause unemployment to rise - if the same number are still looking for work - because now we’d have 8/200 = 0.04 or 4% unemployment.

In reality, a ton of other people were also laid off. How much was real and how much was due to companies agreeing with employees that they’d be let go, then re-hired post-pandemic and so on is a total mystery. In the end, unemployment in the USA jumped from 3.6% to 14.7% seemingly over night.

The Challenge Today: Vanishing People and “Tight Labor Markets”

The challenge today is that the unemployment rate fell back down to 3.6%, but the labor force participation rate is still only about 62.2% (today) instead of 63.4% (pre-Covid). That means there are still about 4 million people[3] not in the labor force that were in the labor force pre-Covid.

If all 4 million people re-entered the labor force and looked for work (i.e., were initially unemployed) then unemployment would be 5.4%. If, however, they return to work with jobs (returning to their old jobs, for example) this would drive the unemployment rate down and may be the cause of some of the low unemployment we observe today. The “true” unemployment rate today is probably between the 3.6% we see and the 5.4%, but we don’t know exactly[4].

That means we don’t know if it’s true that labor markets are super tight today or not. Normally we’d know if labor markets are tight by looking at wages. If demand for workers is relatively high, then wages will rise. That’s a tight labor market.

Today wages have gone up some, but by less than inflation. Wages are rising about 5% a year but inflation is around 8% a year so real wages are actually falling at 3% a year. No wonder businesses are hiring more and more people! They get them for cheap because they charge 8% more for the goods they sell but they only pay their employees 5% more than before. Of course other costs are rising too so businesses might still lose money. But one thing is for sure: labor is relatively cheap. In terms of our assessing the health of the US economy, however, relatively cheap labor is a sign of a slack labor market, not a tight one.

Are We in a Recession?

So, I think all this will unravel quickly. With wages rising slower than inflation, people can buy less and less. This lowers demand for goods and services over time but that also means businesses will lay people off as demand dries up.

And I think the realization of all this is happening now and through the summer. The fact that GDP was negative in the first quarter suggests there are more problems than the numbers indicate. We still haven’t woken up from a dream, so to say.

A second quarter of negative GDP will be a bad sign for sure. But official unemployment numbers are still strong albeit they are misleading for the reasons discussed above.

So, when the NBER will officially call this a recession is anyone’s guess. They look at a number of factors and none of it is totally clear. And it doesn’t actually matter for our every day lives.

What matters is personal well-being. That’s it. GDP is just a number. GDP can be high and you can be miserable. So it doesn’t really matter. These numbers are just numbers we look at as indicators of what might actually be happening in the economy. The numbers are a mess right now. So it’s really hard to see clearly.

That being said, two things are clear to me:

Inflation will remain high and interest rates will rise this year. That will be painful. And,

it will be most painful and brutal for those least able to afford the burden. When you live paycheck to paycheck inflation hurts a lot and if your real wages are falling, then you daily feel how much worse off you are. That is really, really hard.

We will enter a recession this year. The economy is slowing already and unemployment will rise.

I think the sh*t will hit the fan this summer when higher interest rates, slower global economic growth, and higher prices truly settle in so we feel the pain and everyone wakes up from the collective dream. Whether we are technically there today, tomorrow or 3 months from now is only of academic (and possibly political) interest but irrelevant to the average person.

[1] Technically I use approximately the USA’s actual numbers. Population is 329.5 million and with labor force participation at 63% the labor force would be 207.6 million.

[2] Technically, the pre-Covid unemployment rate was 3.6% so 207.6 * .036 = 7.47 million people who were unemployed and hence 207.6 – 7.47 = 200.13 million were employed.

[3] 62.2% times pop of 329.5 is 204.9 million while 63.4% of 329.5 is 208.9. The difference is 4 million people.

[4] At 3.6% unemployment rate is 7.38 unemployed divided by 204.9 in labor force. If all 4 million return then the 7.38 goes to 11.38 and the 204.9 goes to 208.9 (11.38/208.9 = .054 or 5.4%).