Government is too big. There’s no other way to say it.

We see signs of this in many aspects of our lives, but for a Global Econ article, I’m going to focus on the financial-economic side of things. Today, I’d like to share positive examples that may give us all some hope that things can turn around.

(This is aimed at my friends and readers who frequently comment “Great article Chris, but now I’m totally depressed”. I hope that today, this ends on a high note leaving you more positive :-)

I’ll start by setting the stage, which, to be honest, is pretty negative. But then I’m going to share hopeful examples that tell us that we can still turn things around!

The Problem in a Global Context

In the United States, the government has grown dramatically over the last 50 years, and this is now reflected in our own government’s numbers on current debt and deficits, as well as their projections going forward.

Historically, our government’s budget deficit as a percent of GDP was around 3.7%. Today, it’s about double that, at 7% of GDP, and it’s projected to remain around 6.5-7% for at least the next 10-20 years, if not longer. Every year that we are short of funds, we borrow more, and therefore the debt-to-GDP ratio is also high and expected to stay at 100% or more for the foreseeable future.

This is a problem. Don’t forget that governments don’t have any money of their own; they only get revenue by taking it from private citizens. Ever growing government spending means that they must take more and more money out of private hands, out of the economy. As less and less is remaining for the private sector to allocate, invest, save, etc., growth necessarily slows. There’s nothing good about this.

What’s driving it in the United States? Spending, plain and simple.

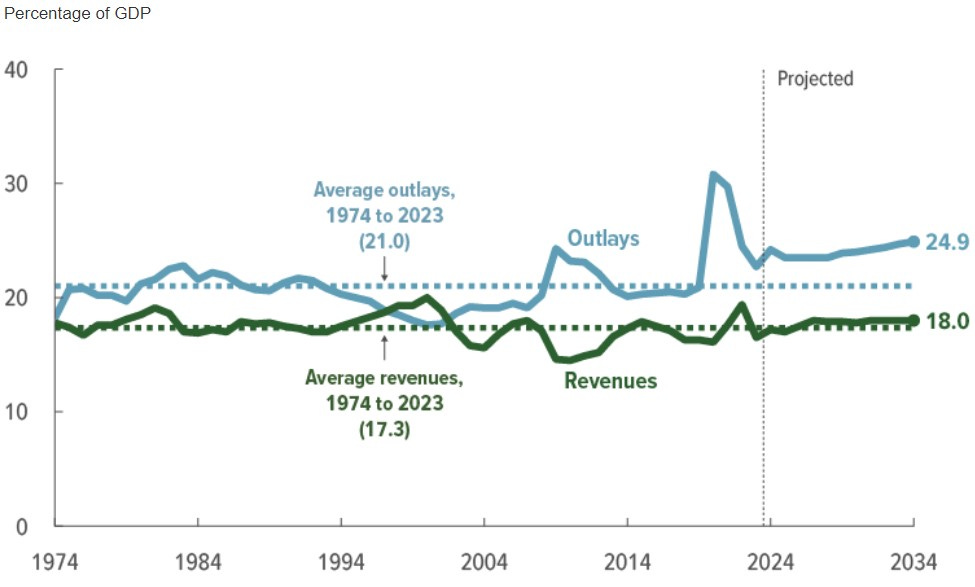

The government’s revenue has remained fairly consistent at around 17% of GDP since the 1970s. Today, it’s actually up to around 18% and is projected to stay at that level for years to come. Spending, on the other hand, has increased from an average of about 21% of GDP to around 24% and is only expected to grow in the coming years. This is a spending problem. The Congressional Budget Office graph below illustrates these trends well.

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

The United States is not alone in this. As the International Monetary Fund (IMF) writes in their April 2024 Fiscal Monitor, (my emphasis added in italics)

“While monetary policy remained restrictive in more than 85 percent of the world’s economies in 2023, only half of them tightened fiscal policy, down from about 70 percent in 2022 .... Revenue windfalls from inflation surprises dwindled … and spending remained high as a result of legacies of fiscal measures to address the pandemic crisis and the introduction of new fiscal support measures in many economies.” (p.1, Chapter 1, Fiscal Monitor)

This suggests that due to high inflation everywhere, governments tightened monetary policy and raised interest rates to slow demand and curb inflation. However, not all of them are cutting government spending or tightening their fiscal policies. On the contrary, spending is actually rising in many places, like the USA.

The IMF again (my emphasis in italics), explains the new spending problem:

“Increased social spending was the main driver of higher spending in emerging market and developing economies. In advanced economies, higher spending reflected a slow unwinding of pandemic crisis subsidies and transfers (Figure 1.2, panel 2), alongside new industrial policy measures, subsidies, and tax incentives (Japan, United States). Higher nominal interest rates pushed up net interest outlays in most economies”(p.1, Chapter 1, Fiscal Monitor)

These are policy choices. An alternative choice would be not to increase spending on these things.

Lest you think it’s not possible, consider Europe where Euro-area countries signed the Maastricht Treaty which requires each country to keep debt at 60% or less of GDP and deficits at 3% or less of GDP. While they loosened these rules during the pandemic, they are now tightening budgets across Europe in an effort to return to their normal, lower levels.

Europe is not known as a bastion of small-government-radical-free markets. In fact, European countries are often cited by American left-progressive-socialists, like Bernie Sanders and others, as examples of the "socialist market economies" that the U.S. should follow! But the Europeans realize that government bloat distorts their economies, hinders sustained economic growth, and becomes a financial weight around their proverbial necks.

But enough about the problems—this can all be turned around.

The Greatest Ponzi Scheme: Problems and Solutions

Today’s column is meant to be honest about our problems while also reminding us that there are solutions and historical examples where bad fiscal situations have been turned around.

There is still hope, but we need governments to act and act soon.

All the information below is taken from Les Rubin and Daniel Mitchel’s book, The Greatest Ponzi Scheme on Earth, which discusses U.S. financial problems, how we got here, and solutions to fix them. I appreciate that they don't just complain—they offer examples and solutions to specific problems. If you're interested in additional ideas for fixing Social Security, other entitlements, and more, you can find their book and other resources here.

(Note: In full disclosure, I am an advisor to Mainstreet Economics and fully support their mission to bring basic economic education to all Americans in a non-partisan way and encourage them to “Learn Economics and Vote Smart”. I make no money from Mainstreet Econ’s site, work or any book sales, however.)

Some Success Stories

In the stories below, I focus only on the policy changes that helped clean up fiscal messes. In Rubin and Mitchel’s book, they discuss other policies in these countries and several other examples as well.

Switzerland

“One of the world’s most prosperous nations, Switzerland enjoys a relatively small burden of government spending when compared to other European countries.” (p. 103, The Greatest Ponzi Scheme on Earth)

“…voters approved a referendum in 2001 that imposes a spending cap on the central government. Technically known as the “debt brake,” this measure was approved by an astounding 84.7 percent of voters. The debt brake limits spending growth to average revenue increases over a multiyear period, as calculated by the Swiss Federal Department of Finance. Some people think of the debt brake as being akin to a multiyear balanced budget requirement. There can be a deficit in one year (perhaps because of an economic downturn), but that deficit will be offset by mandated surpluses in other years.

Has Switzerland’s spending cap been successful? The answer is clearly yes. Ever since the debt brake was adopted, government spending has increased by an average of just 2.2 percent per year.” (p. 104-105, The Greatest Ponzi Scheme on Earth)

I personally like the debt brake solution. It seems inherently functional. It’s not a radical proposal; it allows for some deficits during a recession but then requires that they be paid off and offset with subsequent surpluses. It seems very doable.

Switzerland turned things around. The U.S. and other countries can too!

New Zealand

“New Zealand’s economy was stumbling in the 1980s. There was a range of bad policies, such as high tax rates, a heavy burden of government spending, protectionism, regulation, and subsidies.

Interestingly, it was a supposedly left-wing government that began moving the country in the right direction. After the Labour Party took power in the mid-1980s, it began to liberalize trade, lower tax rates, privatize, and deregulate.

But the big improvement in fiscal policy did not happen until the early 1990s. Building on the success of the Labour Party’s reforms, the National Party decided it was time to control spending. Lawmakers were remarkably successful. As seen in the chart, there was a five-year spending freeze between 1992 and 1997.

During this period, the economy grew, but spending did not. The burden of spending (measured as a share of GDP) fell dramatically. But look also at what happened to deficits and debt. Because lawmakers dealt with the underlying problem of excessive spending, they automatically solved the symptom of red ink. New Zealand went from a big budget deficit to a budget surplus. The national debt, measured as a share of the economy, fell by more than half.” (pp. 111-112, The Greatest Ponzi Scheme on Earth)

New Zealand shows us, once again, that fiscal restraint is not a left or right issue—it’s a common-sense, we-need-our-government-and-economy-to-function issue. A five-year spending freeze sounds like a compromise that even a very divided America could agree on. I’d prefer something more permanent, like the Swiss debt brake, but I would definitely settle for this if we could get it.

New Zealand turned things around. The U.S. and other countries can too!

Ireland

“Forty years ago, Ireland was a very poor country by European standards. Now it is called the “Celtic Tiger” and is widely recognized as an economic success.

… In the 1980s, back when Ireland was a poor nation, there was a very heavy burden of government spending. This fiscal burden was suffocating the economy and causing a buildup of debt. Irish lawmakers finally realized that something needed to change. They decided to restrain the growth of government. Indeed, they wound up freezing government spending between 1985 and 1989.

…This gave the private sector some much-needed breathing room. Growth improved, and the burden of government spending fell as a share of GDP. And because there was progress tackling the problem of too much spending, the symptoms of deficits and debt became more manageable.” (pp. 112-114, The Greatest Ponzi Scheme on Earth)

The Irish story is similar to the New Zealand one. Again, it’s not a perfect solution, but it shows that when things get bad enough, people demand that their politicians restrain spending—and it can be done. A four-year freeze is better than no freeze.

Ireland turned things around. The U.S. and other countries can too!

Canada

“Years of excessive spending under both Liberal and Conservative governments significantly increased Canada’s fiscal burden. Chastened by fears of a fiscal crisis, politicians finally began to impose some fiscal discipline in 1992. Over the next five years, government spending, on average, grew less than 1 percent annually.

This period of spending restraint paid big dividends. Because government grew slower than the economy, the overall burden of spending in Canada dropped by 9 percentage points of GDP— from 52.5 percent of economic output to 43.5 percent of output. This fiscal discipline also eliminated a large budget deficit. Red ink was equal to 9 percent of GDP in 1992. By 1997, Canada had a balanced budget.” (pp. 114-115, The Greatest Ponzi Scheme on Earth)

I’d prefer the Swiss debt brake. If you can’t get that, I’d take the 5-year freeze. If not, then the 4-year freeze. And if none of that is possible, I’d still accept five years of 1% or less government spending growth.

Canada turned things around. The U.S. and other countries can too!

Ending on a High Note

I focused here exclusively on the government’s fiscal burden, which is rapidly getting out of control in the United States and other countries. At the bottom of this column, I included a data table from the IMF Fiscal Monitor. I highlighted the U.S. vs. EU numbers, but you can see data from other regions as well. Some are set to improve, while others are expected to worsen.

The point of today’s column is simple: Yes, things can and do get out of control. But it’s also possible to turn things around, control spending, pay down debt, and get back in balance.

Many countries have done it. The Europeans are moving in that direction. Switzerland has done it. New Zealand did it. Ireland did it. Canada did it. It looks like Argentina is doing it today.

Some countries combined fiscal reforms with other pro-growth policies, while others did not. Some countries maintained their good fiscal policies—like Switzerland—while others did not. But the point is that IT IS POSSIBLE.

In all these cases, the follow-up is clear: over a short period, deficits turned into surpluses, Canada ran a balanced budget, debt-to-GDP ratios dropped significantly, and so on. It’s true that Canada, New Zealand, and Ireland backslid after these successes, but not all the way back to where they started. These examples show that politicians of all stripes eventually reach a point where they realize something must be done, and they do it. It is totally possible.

We can turn things around in the United States. You can turn things around in your country. There are plenty of examples and plenty of recommendations.

Google, read, think. Email me if you want guidance on resources for options and solutions. But don’t lose faith. We can collectively still change course and set things back on a better path. Better to do it now before we hit another crisis.

In the words of Les Rubin, “LEARN ECONOMICS, THEN VOTE SMART”. I think that’s step one.

Thank you for reading.

Sweden is another success story. In 1996, it was decided that the budgeting process should be made stricter, one of the new rules being that there must be a one third of a percent of GDP surplus on average over a business cycle. Since then, government debt has gone from over 70% to less than 20% of GDP.