I’m tired of hearing “Bad news is good news”.

It seems that every market commentator and market participant is watching for one thing and one thing only: the sign that the Federal Reserve (the FED) will change course and not raise interest rates anymore. Nearly every discussion I hear today in the financial news is about when the FED will pivot. By Christmas? Next year? And so on.

Everyone understands – so they claim – that the FED must raise rates to fight inflation. But higher rates are bad for trading stocks[1] so investors want it to end. Also, everyone understands that higher interest rates will slow demand and cause a recession.

Market watchers seem convinced, however, that when the economy really takes a nosedive, the FED will stop raising rates. Everyone watches for each report with baited breath, hoping for a sign that things are worsening and “ah ha” the FED can stop raising rates now.

The one overwhelming conclusion I can draw from this is that the Federal Reserve has little to no credibility. No one it seems actually believes the FED will raise rates and hold them high until inflation is truly gone from the economic system.

The FED’s Experience

This is a problem for the FED.

It reveals a lot actually. Since, let’s say 2000, the FED has functioned in an economy with low inflation. It is not clear that low inflation was the result of good FED policy. Maybe it was, maybe it wasn’t.

Many have argued that globalization led to constant low-price pressure and kept inflation largely contained. That really started in the late 1990s with the opening of China to world trade, the opening of the former Soviet communist countries to freer societies and economies and to world markets.

Others have argued that population dynamics also saw the “baby boomer” generation still running through the employment pipeline, keeping labor markets flush with available labor and hence keeping wage pressure largely contained as well.

The FED, for its part, focused on liquidity issues, systemic banking issues and similar economic “plumbing” issues, for lack of a better word. It could do this, in part, because inflation wasn’t a problem.

Now, to give credit where it is due – because I am not actually against the FED – the FED also did not cause extra inflation in the economy. After each attempt to stimulate the economy – after 9/11 and again after the 2008 financial crisis – the FED reduced money growth quickly. Each stimulative effort was a short injection of money growth and low interest rates quickly followed by less money growth. They were jabs to the economy, not full body tackles to the ground.

But a very strange thing happened. In the still of the night and without much fanfare, the FED switched to a policy of ample reserves. That means the FED pumped the banking system full of money, then paid the banks interest on that money as long as they keep it in “reserves” which is actually the name of the banks’ “bank accounts” at the FED itself.

When something is in total, absolute abundance, its price is zero. Not surprisingly, with the banks flooded with money, interest rates – the price of holding money – stayed near zero for many, many years after the 2008 financial crisis.

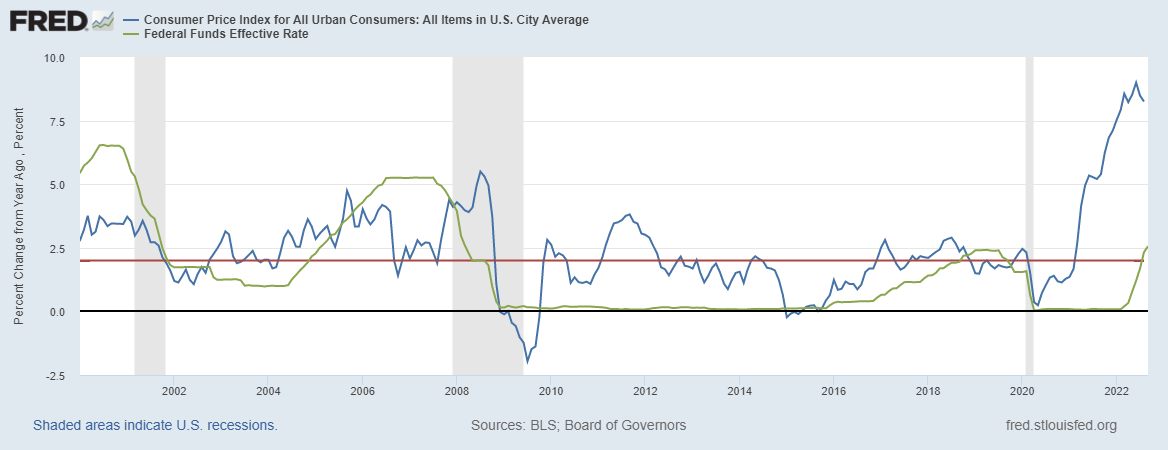

The graph here shows the FED’s inflation target (red line at 2%), actual inflation (blue line) and the FED’s interest rate (green line). Notice how much the green line changes after the recession from 2008 to 2009 (grey area).

Before 2008, the interest rate moved up and down. Any time it was less than inflation, policy was considered to be stimulative and any time it was above inflation, restrictive. For eight years after the 2008 crisis they couldn’t get rates off the floor of zero.

The FED’s Conclusion

The FED’s conclusion from the post-2008 period has been quite self-congratulatory. It is that (a) it has mastered the manipulation of inflation, and that (b) the FED is seen as so credible by markets that it can literally control future inflation simply by “forward guidance”, that is, by announcing it.

The conclusion that the FED has mastered the manipulation of inflation comes from the observation that inflation was low after 2008. But a casual observer wouldn’t necessarily draw that lesson from the above graph.

Instead, it looks a lot like pre-2008 interest rates were doing something and afterwards they weren’t. Pre-2008, higher interest rates led to less inflation and lower interest rates led to more inflation. There was a long and varied lag, but it seemed to hold.

The graph starts with high interest rates (green line) that eventually drive inflation down (blue line) although it took a few quarters to have the intended effect. Then from 2002 until 2005 or so, interest rates were low, stimulating inflation which slowly began to rise – again with a bit of a lag – so that in 2004 the FED had to start raising rates to fight the rising inflation.

Many observers feel the FED raised interest rates too far in that 2004-2007 period and we see they got high indeed, then inflation dropped like a rock. That was the period leading to the housing bust and sudden financial crisis. But the lesson for the moment is that interest rates moved and inflation eventually followed suit.

Again, without going into too much detail, the FED then changed our monetary system in 2008. Instead of using open market operations – increasing/decreasing the money supply by buying/selling bonds to move the interest rate – the FED started paying banks interest on the reserves they hold and then flooded them with reserves.

This graph should disturb you. It starts in 1960. Banks have always held reserves. Traditionally when someone made a deposit at a bank, the bank kept part of that deposit “in reserve” which meant either in vault cash or in the bank’s “bank account” at the FED.

In the traditional environment, had the FED suddenly added over $1 trillion in reserves to the banking system, banks would have lent that money out and the resulting massive stimulus of spending would have driven inflation through the roof.

This massive increase didn’t lead to hyperinflation, however. That’s because the FED did one other thing. They started paying interest on the reserves that banks hold. So today, the FED pumps the system full of reserves (as you can see in the graph) and then pays banks to hold the reserves. As a result, the reserves don’t flood the system as loans and lead to a massive increase in the money supply. The “ample reserve system” always has plenty of liquidity (i.e., “ample reserves”) if needed but it doesn’t cause inflation.

The FED’s primary tool today for controlling interest rates is by controlling the interest rate paid on reserves themselves. This policy changed the way the system functions and decoupled interest rates from the money supply.

Back to the Main Story…

With interest rates disconnected from the money supply, it’s not clear exactly how the FED controls inflation. Period. And, for sure, they don’t control inflation the same way they used to.

So what fundamentally determines inflation?

Well, the FED’s current thinking assumes that the FED’s forward guidance nails down long-term inflation because they are so credible that, whatever they say, that’s what markets believe.

Given that long-term inflation is pinned down by FED credibility, then in the short run the FED’s challenge is (a) to keep the system liquid and (b) prevent inflation from getting out of control. It does that by manipulating supply and demand conditions via interest rates.

The first part’s fine. They flooded the banking and financial system with reserves. No one doubts this. We can see it in the graph.

The second part is questionable. If short-run inflation doesn’t come from money growth, but is determined by interest rate policy – as the FED claims – then how did the FED keep interest rates at zero for about eight years - from 2009 to 2016/17 - without massive inflation? And when they started raising rates in 2016, why didn’t inflation fall over the coming four years? Four years is a long lag.

FED officials will tell you that inflation was stable the whole time because it was staying around it’s long-run inflation rate and that’s pinned down by the FED’s amazing credibility. Just look: We said it should be around 2% (our target) and conveyed that officially through our forward guidance and … voilà … it was indeed around 2% and even below!

Auernheimer’s Tigers

This reminds me of a story my dissertation advisor, Leonardo Auernheimer, used to tell. Two people are riding on the morning commuter train to work in, say, New York. One gentleman is sipping coffee and reading the morning news. He notices the other gentleman doing the same, but periodically he tears up a small piece of the newspaper and tosses it out the window. After a while, the one asks “why are you doing that?” The other replies, while tossing another small piece out the window, “to keep the tigers away”. The first replies, a bit startled, “but there aren’t any tigers here”. And the other smiles, “see, it works!”.

From 2000 until 2020 the FED just announced inflation would stay around 2% and it did. How much of that can we attribute to FED credibility?

Conclusion

The FED today claims that it will stick to its guns, raise interest rates and fight inflation until it falls back to the 2% target. This is their forward guidance.

Every time I hear market commentators today say they are watching the next employment report, consumer confidence report, inflation report or what-have-you-report because they are watching for the bad news that causes the FED to stop, I realize the FED is not credible. Everyone’s betting on when the FED will cave and capitulate.

I’m not sure how much credibility the FED has. Therefore I’m not sure their forward guidance is as valuable as they think it is. And therefore I have no confidence that the FED actually understands what pins down long-run inflation. I’m not sure we economists understand it today. It’s not money anymore. It doesn’t look like its interest rates anymore. And, I really don’t think it’s FED credibility.

[1] A higher interest rate raises the opportunity cost of investing in stocks, makes the companies less profitable (by raising their borrowing/financing costs) and hence lowers the stock prices.

Thanks Nikhil.

This week's Friday release will be all about the “FED causing inflation/recession” theory. So, check it out and let me know if you have questions. It also gets to where the belief that the Fed has so much control comes from. In short, the Fed can influence economy wide demand by raising/lowering interest rates. (How precisely is a different question). That will also move prices (inflation) and unemployment. In trying to fight inflation - which I think ultimately the Fed can do just less clearly and precisely as they think (something they seem to be admitting lately) - the Fed tightens conditions and causes a recession too. But it is NOT clear that "in order for inflation to return to normal" we "must have" a recession. But it would likely take longer to get there. Hope that helps and thanks for reading

I am only an economics undergrad right now, so don't judge, but could some of this have to do with China's economic influence?