The Japanese Economic Warning

In May I had the pleasure of virtually attending the one-day event: “How To Get Back On Track: A Policy Conference” hosted by the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. There’s a website with videos, downloadable presentations, and some papers as well (see footnote for link[1]).

The luncheon speaker was a former Governor or the Bank of Japan, Haruhiko Kuroda, who spoke about “Inflation Targeting in Japan from 2013 to 2023”. This provides a great introduction into the economic warning that Japan’s experience presents.

There’s a lot here. I’ll unpack pieces.

The Japanese Warning: Part I

The Japanese “economic miracle” is what many call the post WWII period in Japan. From about 1950 to 1980 Japan went from a devastated economy to a global economic powerhouse that surpassed all other economies in the world except the USA’s.

The miracle occurred through governmental, social, and economic reform that was inspired and supported by the United States. And, while there were many market reforms, and a pro-market slant to it all, the miracle was also achieved by a lot of state-directed economic development which was seen. Many viewed the Japanese – and German, by the way – system as a challenge to the American “pure free-market” approach.

The Japanese government helped form manufacturing groups, encouraged explicit export-led growth, and used strategic industrial policy to choose sectors for development. Japan was simultaneously a testament and a challenge to democratic-capitalism. The critics of free markets seemed to have a point, as government direction and strategic industrial policy were seen as picking the key industries of the future. The thinking was that markets were too short sighted. Strategic government industrial policy was needed for a longer term view, and to gain strategic advantage in the global economic war. They definitely had an example in Japan to point to.

By the 1980s Japan had become the second largest economy in the world, but never quite surpassed the US economy. This was an amazing feat with a territory and population fractions of the size of the US. The population, for example, in 2022 was only about 125 million people compared to 333 million Americans. And, the US economy had been more market oriented and growing for about 100 years. Japan performed its miracle in about 30 years[2].

Then it stopped.

Since about 1990 the Japanese economy has largely flatlined.

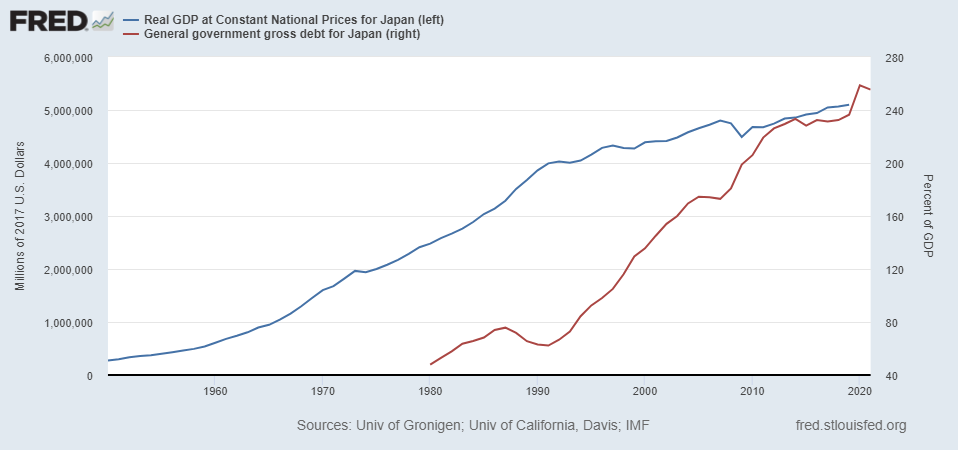

Why exactly 1990 remains a mystery, but since that time the economy grew some, but not nearly as rapidly as pre-1990. The economy was growing by about 1 trillion USD every 10 years from 1950 to 1990. From 1990 to about 2020 (the chart technically ends in 2019) – a 30 year time span – the economy grew by 1 trillion USD.

Japan’s strategic economic system seemed to have run out of steam. The discussions since then have been about how the Japanese strategy ossified the economic system, picked many non-winners, and overburdened itself.

The 1990s were full of a series of efforts to regain the growth. The famously low Japanese unemployment, touted as an achievement in the 1950-1990 period when the natural rate of unemployment in Japan seemed to be 1% to 2%, was now seen as a hindrance. People don’t switch jobs. They commit for life, and don’t cross pollinate companies with ideas. As reforms took root to make a more flexible labor market, unemployment rose up to 5% over the 1990s. But nothing moved the economic needle. The economic engine was still stalled.

Policy makers promoted more government programs to stimulate growth. What seemed to have worked to stimulate, guide, and motivate the economy before, did nothing but run up debt. They were pushing on a string.

Debt in Japan went from about 40% of GDP in 1980 to well over 240% of GDP today. The accumulation of debt was right when the economy flatlined. The higher debt-to-GDP didn’t cause the flat GDP growth, but it certainly did not stimulate the economy.

The world mysteriously turned on a dime on the Japanese in 1990, and the miracle vanished into thin air. No one truly knows why. There are theories, but no one truly knows.

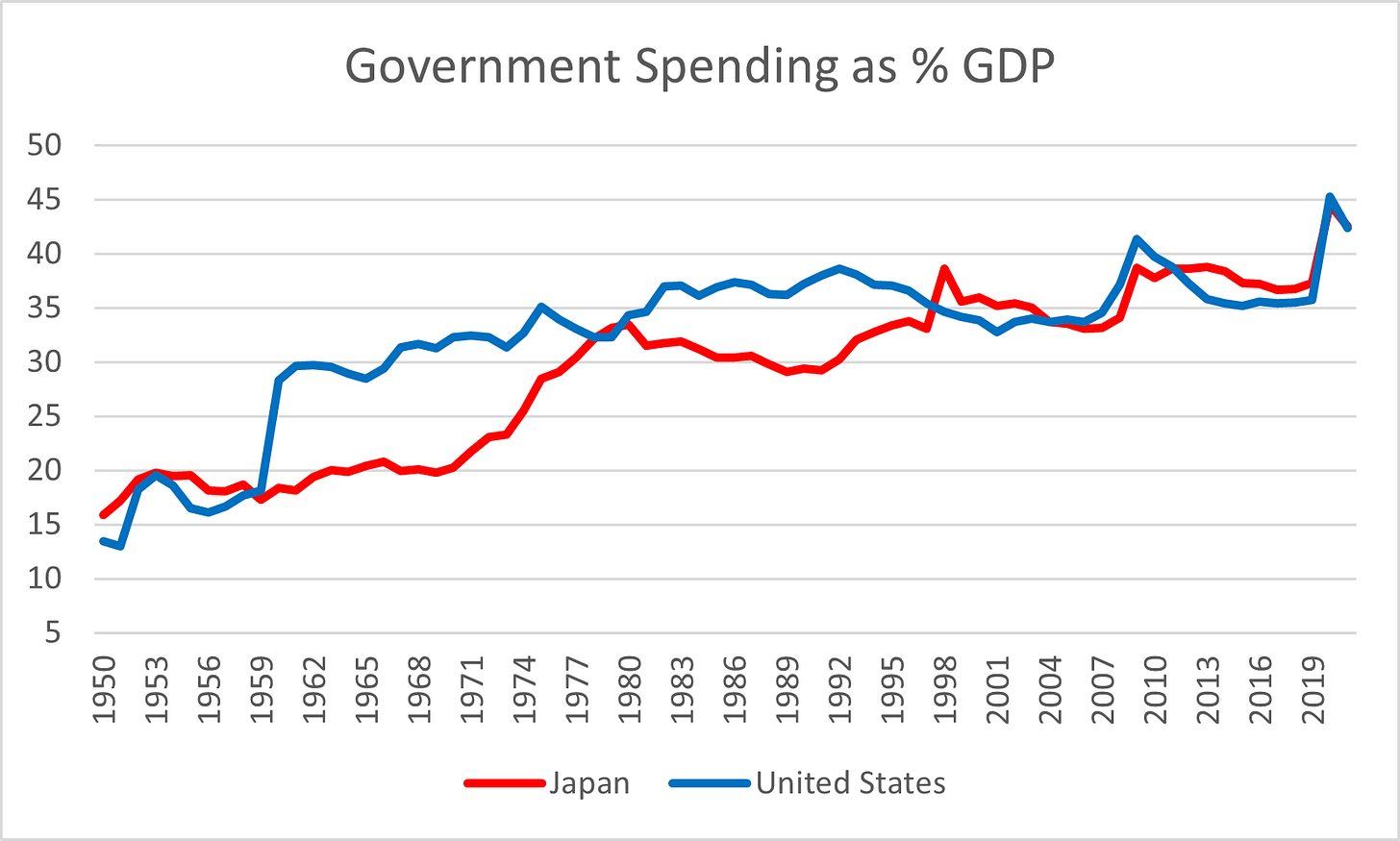

It’s worth noting that government spending as a percent of GDP was not really higher in Japan than in the US. As a matter of fact, for most years after 1960, the US government’s spending as a percent of GDP was higher than Japan’s. This is clear in the following graph based on IMF data[3].

Anyone who thinks government spending will permanently spur GDP growth should think again. In trying to maintain spending it couldn’t afford, the Japanese accumulated debt, and there’s every indication based on history and theory that excessive debt to GDP becomes a drag on an economy’s performance over time.

This part of the warning, however, is not mainly aimed at the United States. Sure, we should all worry about our rising debt-to-GDP levels. This part of the warning, if it’s for any country, is for China.

To start, export-led growth has its limits. To drive exports in practice means driving exports beyond imports to generate a trade surplus[4]. For reasons a bit too long to explain here, a large and persistent trade surplus requires a country to save more than it invests domestically. In this scenario, savings flow out of the country, and gets invested in other countries (on net). This is another way of saying that the Japanese persistently underinvested in their own economy.

Additionally, industrial policy with government direction seems to have some limited benefits initially. Likely, I believe, because it focuses resources into known technologies, but naturally also under-allocates to alternative opportunities. This generates an initial level effect by raising output today, but slows the rate of growth in the future. In any case, what seems to happen over time is that a government industrial complex gets built up and solidifies, creating large immovable blocks in an economy. And, those structures increasingly distort both governmental and private resources over time.

Those are two clear and present dangers for China today.

The Japanese Warning: Part II

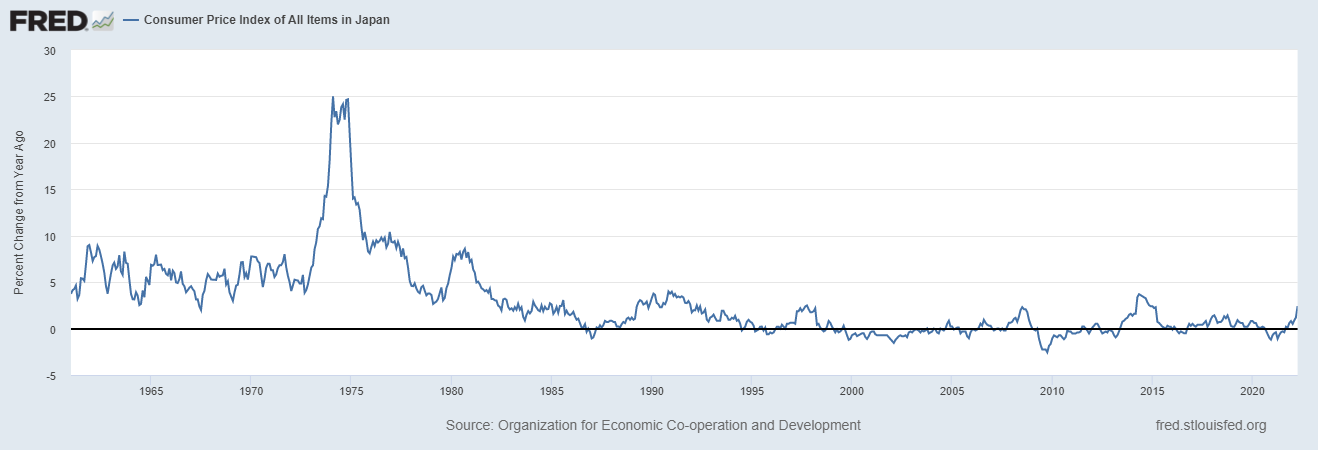

The part that worries me for America and many other countries today is the role of monetary policy in Japan post 1990. At around the same time as the slowdown in GDP growth, Japan also slipped into a period of very low inflation, and then deflation for nearly 15 straight years.

And here is where we pick back up with the Japanese Governor’s luncheon remarks….

First, I share my concerns in as brief a space as I can, and then the Governor’s remarks.

My Concerns

Japan pioneered the kind of monetary policy and monetary intervention in the economy that we Americans and policymakers in most other countries have followed slowly but surely since the Great Financial Recession of 2008/09.

In 2001, the Japanese invented what is called QE, “Quantitative Easing”. The US Fed and other central banks introduced QE in 2008.

The Japanese expanded what the Japanese central bank could buy. Traditionally most central banks would only purchase government bonds. Today the Bank of Japan buys stocks, bonds, ETFS and a range of other assets. The US Fed and European Central Bank have recently followed suit.

The Bank of Japan became so dominant in its domestic financial system that, as I understand it, there are many trading days when no private participants even trade in the bond market for Japanese government bonds. It’s just the Bank of Japan. The US Treasury market is the deepest and most liquid in the world so this is not likely for the US government’s bond market, but is a danger for others. And, as I will write more about soon, our overnight interbank market, the “federal funds market”, where the Fed sets the federal funds rate, has been largely drained of private participants in recent years and is today dominated by mostly governmental or government-backed bodies like Freddie and Fannie Mae, our quasi-governmental mortgage funds.

The Bank of Japan created YCC, yield curve control, which means they no longer target just short term interest rates, but also long term interest rates. This is partially done by QE which includes central banks purchasing long-term assets, and hence influence long term rates. No other country (yet) explicitly tries to control the whole yield curve at once, but QE policies buy long-term assets too, and we talk about influencing long-term rates.

My concern is that Japan was not able to get inflation positive for 15 years until a crisis. The US Fed and most other “inflation targeting” central banks have modified their financial systems too, modelled after Japan’s innovations. Before COVID, the talk in global monetary policy circles was also about why these countries had inflation persistently below their targets. They weren’t facing deflation (yet), but they struggled to get inflation up to target.

Is that a symptom of the system? I don’t know.

It does tell us, however, that the central banks are not able to control inflation using their modern monetary regimes. That means we don’t fully understand what causes inflation in the modern world. I believe we are watching this problem play out in real time today as central banks battle inflation. It’s not clear to me at all that they understand the actual mechanisms driving inflation any more.

More on that later. For now… Japan…

A Japanese Canary in the Monetary Coal Mine? Governor Kuroda’s Luncheon Talk

Video of Governor Kuroda’s luncheon talk for anyone interested (see footnote[5])

Haruhiko Kuroda was Governor of the Bank of Japan from March 2013 until April 2023. As he explained in his opening remarks, in January 2013, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) announced that it was implementing an inflation targeting regime, setting a 2% target for inflation. The goal was finally to escape the past 15 years of Japanese deflation[6].

In a joint statement with the Japanese government, the BOJ explained that it aimed to hit the 2% target “at the earliest possible time” with a view to achieving it within 2 years.

He explained that this was necessary because Japan had suffered deflation since 1998. The average inflation rate for the 1998 to 2012 period was -0.3%, economic growth was low and unemployment was high at 5%. Additionally, he later noted, hourly wages also fell by 0.4% for that same period. Pretty dismal economic performance indeed.

What proceeded for the rest of his talk was what central bankers all tend to do. I’m sure he’s a wonderful person, and I’m sure he and all central bankers believe this, but essentially their stories always go like this: we aimed for inflation to be X. It was Y, but it would have been X based on our actions. The problem was that … happened, was outside our control, and prevented us from achieving X[7]. Governor Kuroda’s Luncheon Talk was sadly no different.

As he explained, in January 2013, the BOJ agreed to achieve the new 2% target through the QE policy they invented in 2001 and then expanded in the 2003-2006 period.

In 2008 they expanded it further, permitting the BOJ to buy assets other than just Japanese government bonds. They began buying stocks as well. Nevertheless, deflation and high unemployment persisted. This expansion of QE lasted from 2008 to 2013.

In 2013, further expanded QE to meet the new target. Surely this time, QE will work! They called the new, expanded QE, QQE for “quantitative and qualitative expansion”. Inflation didn’t move in 2013.

In 2014 it spiked in Spring to 3-4% briefly, but then fell back near zero. The Governor explained the spike was due to import price hikes that spring. Nevertheless, this and their announced target seemed to have raised long-term inflation expectations higher in Japan, something they had been hoping to achieve.

By end of 2014, inflation was again only 0.4%. They expanded QQE further, buying even longer-term assets, and also expanded the monetary base in Japan. But inflation didn’t budge. Kuroda explained the BOJ felt this was due to high oil prices reducing demand and hence keeping inflation low.

In 2015, average inflation was 0% but unemployment had fallen to 3.4% and GDP growth was around 1.6%. So, in the BOJ’s eyes, these were some successes despite external factors preventing inflation from reaching target.

In January 2016, the BOJ introduced a new tool to get inflation up to 2%: the negative interest rate! The BOJ intentionally drove one of the key policy rates in Japan to -0.1% and held it there in order to stimulate the economy and inflation. It didn’t work.

In July 2016, they expanded QQE to allow the purchase of ETFs (exchange traded funds), and launched a study of the QQE and negative interest rate policy mix.

In September 2016, they finished the study, and agreed to add two new ingredients: YCC (yield curve control) and forward guidance. And, they agreed to keep this whole new regime in place until inflation hit 2%.

YCC, as explained before, meant that the BOJ targeted both short and long-term interest rates (both the beginning and the end of the yield curve). Policy makers would now essentially control all interest rates in Japan at all time horizons.

Kuroda explained that this was a success. Inflation averaged around 0.5 – 1% over the 2016 to 2019 period. And, the BOJ, believed it would have continued but the government raised taxes on consumption in October 2019 which hurt demand. As a result, inflation never exceeded 1% or neared the 2% target due – alas, once again – to outside influences. But, GDP growth was “sometimes positive” during this time and unemployment by 2019 was near 2.4%.

In 2020, COVID hit. Output and inflation collapsed in Japan as it did in all countries.

In 2021, output sprang back, and unemployment returned to 2.5%. He didn’t mention inflation, but I just checked and it was -0.23% in 2021.

In 2022, finally things were back on track but, as Kuroda explained, “the war in Ukraine erupted in February 2022 which raised energy and food prices enormously, resulting in extremely high inflation – the highest in the last 40 years. Again, Japan was no exception”. Inflation in 2022 hit 2.3%.

Three quotes from his conclusion (11:50 minutes into the video, if you search):

“As I said at the outset, although inflation is currently 3-4%, it will slow down to less than 2% by the middle of fiscal 2023. However, the important fact is a 15 year’s long deflation has been overcome with substantial employment increase and wage increase.”

“Based on the significant improvement in the economy, we can now envisage the 2% inflation target will be achieved in the near future”.

“I’m sure that without the 2% inflation target and strong commitment by the Bank of Japan, we could not have overcome Japan’s persistent deflation.”

I know he and the BOJ and most central bankers believe their frameworks and ideas are right and work if only for these pesky external shocks, and sometimes the wrong beliefs held by market participants. But, I’m sorry, to me it sounds like the BOJ does not control inflation. I don’t know how else to understand this.

And, it seems, I’m not alone in my questioning of the regime they’ve implemented. Professor Sebastian Edwards, an outstanding international macroeconomist at UCLA, asked during Q&A something along the lines of “when I teach about Japan’s YCC in my money and banking courses, my students ask how the bank can do this without worrying about distorting the market and interest rates by controlling both short and long market rates”. But the Governor never answered. Or, at least I didn’t understand his answer.

Conclusion

I worry that we – monetary economists in academia, and especially those at central banks – have mucked up the financial system in recent years with a thousand interventions until it doesn’t operate the way we think it should.

If the government and/or government-backed agencies are the only participants in many markets, and all actors are under government regulation and control, and, further, the interest rates in those markets are controlled by a government agency (the central bank), then the interest rates aren’t market prices anymore. They lose all the information value we expect from them. They lose all the allocative functions they perform in normal markets.

Professor Edwards’ students could see it. My students could see it when we covered the same topics this Spring semester in my money and banking course at Quinnipiac University.

But, I don’t know what it all means yet. That’s part of what I’m exploring. I think, understanding what happened in Japan holds insights for what might be happening elsewhere.

Consider this a first primer on Japan. I’m sure I’ll write more on it soon.

[1] Hoover conference link: https://www.hoover.org/events/how-get-back-track-policy-conference

[2] I’m intentionally overstating the case, trying to capture the mood and view of the times. Anyone who remembers the 1980s will recall these arguments and views were prominent. They are fallacious in many ways. It was a miracle, but the 30 years vs. 100 years, for example, reflects that knowledge and human capital are more important to long term growth and well being. And, knowledge isn’t destroyed by bombs the way physical capital is.

[3] IMF: https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/exp@FPP/USA/JPN/%20ESP?year=2021&yaxis=lin

[4] This reflects a misunderstanding at some level. One benefit of the exports is that, of course, domestic businesses sell more, employ more people, and this is good. The other benefit is that the domestic businesses are forced to compete in global markets, forcing them to focus on improvement and efficiency instead of living in a protected domestic market where inefficiencies are rewarded with more government subsidies. But, if government subsidies are used to drive the companies so they can compete globally, this second benefit becomes a cost paid by the domestic taxpayers. And, finally, neither benefit requires that exports be greater than imports. That is, they do not require a trade surplus at any level.

[5] YouTube link:

[6] To get an intuitive feeling for why everyone hates deflation, imagine deflation of, say 5% a year. All prices fall at 5% every year. Now, imagine your boss explaining to you that you did an amazing job this year. You’ve earned a 3% bonus! So next year they will only cut your salary by 2%! That’s a hard pill to swallow, even if technically true. People hate deflation.

[7] Fundamentally, most economists agree that the one thing a central bank can do is determine average inflation over long enough time horizons. Sure, something external may prevent it this month or quarter or even this year. But, when you fail to hit a target for 15 or 30 years, you can’t always blame outside factors.