Welcome to the New Year!

Photo by Anastasiia Rozumna on Unsplash

High interest rates and the lingering possibility of recession feel like the hangover from a hard year of inflation fighting. Inflation still dominated much of the financial news last year, but I don’t think it will dominate this year again. So, it’s worth taking a minute to sort or wrap up the topic, and see where we are. In short, inflation has dropped significantly worldwide, we did not enter a recession in 2023 like most economists (myself included) predicted, and it all turns out to be a challenge for economic models.

New Keynesians and Their Phillips Curve

The dominant view of central bankers around the world, and the dominant models used by economists, are known as New Keynesian (NK) models. These models rely on what’s known as a Phillips Curve (see my old columns “It’s baaack! The Phillips Curve Conversation” and “Who’s Afraid of the 1970s?”). That is, they rely on there being a stable and exploitable relationship between unemployment and inflation, which is represented as a Phillips Curve. In particular, a simplified version of their logic says that inflation rises when unemployment falls and therefore, to lower inflation, we require unemployment to rise.

As we continued to raise interest rates last year, we all therefore expected a recession with those of the NK persuasion watching first for rising unemployment. That would be the signal that the interest rates were working and would therefore lead to lower inflation soon. That decidedly did not happen in 2023 but inflation fell anyway. Hmmm… not a good sign for their models.

Three Major Economies

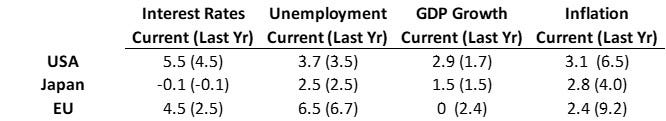

Let’s first look at the United States, the European Union, and Japan. These are the big three, dominant players that drive much of the world’s policy. It also gives a good initial sense of what’s happening around the world.

Source: Trading Economics[1]

For each category I report the latest number from December 2023 (“Current”), and put in parenthesis its value for December 2022 (“Last Yr”). Let’s check column three (GDP Growth) first.

Interestingly, the USA is currently growing the fastest, although that wouldn’t have been anyone’s guess in December 2022. Last year, the EU was growing at 2.4% compared with America’s 1.7%.

Unemployment (column two) ticked up very mildly in the USA, but actually fell in the EU, yet in both countries inflation dropped, from 6.5% to 3.1% in the USA, and from 9.2% to 2.4% in Europe. Japan shows no signs of any change in GDP growth or unemployment at all, and inflation dropped there too from 4% to 2.8%.

Interest rates rose (column one) in the USA and in Europe. Actually, they rose a lot in 2023 in the EU, from 2.5% to 4.5%, while the USA seems to have already been near its peak. Indeed, if we were to look at the middle of 2022 instead we’d see that inflation was around 9% and interest rates were not yet so high. The USA seems to have been ahead of the EU by about six months.

Of course, I often think Japan exists for the sole purpose of confusing economists. Japan shows no change in GDP and no change in unemployment. Japan did not change interest rates, which are still negative, and yet inflation fell in Japan too!

The New Keynesian Phillips Curve logic clearly doesn’t hold at all here. If it did, we’d see higher interest rates causing dramatically higher unemployment (say in the 4% to 5% or 6% range) and the higher unemployment would pull inflation down. We see almost the opposite. Higher interest rates seem to have lowered inflation but without a recession or increase in unemployment.

A Broader Look Around the Globe

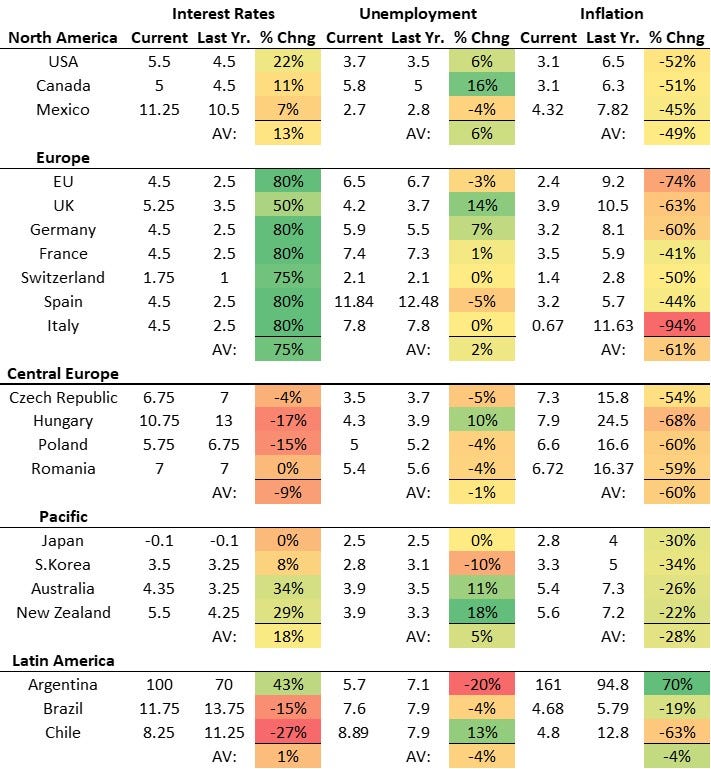

The next table looks at a range of countries. I’ve ordered things left to right with the Phillips Curve timing in mind: interest rates, then unemployment, then inflation. I only report the percentage changes in each. The complete table is at the bottom of this column for those interested.

In summary, we are in better shape than last year. Inflation is down and unemployment didn’t change much at all. While this is good news for us, it suggests that the NK Phillips Curve logic didn’t work so well.

The colors show intensity. Red is the biggest negative and dark green the biggest positive with other shades in between.

North America

The USA raised interest rates by 22% over 2023 (from 4.5% to 5.5%). Unemployment did tick up by 6% but that’s only from 3.5% to 3.7%, not enough for most people to notice. Inflation fell by 52%, down to 3.1% (from 6.5%) by December 2023.

Canada raised interest rates by only 11% over the year, unemployment rose 11% and inflation fell 51%. Compared to the U.S., Canada raised interest rates less, saw a bigger rise in unemployment, but got a smaller drop in inflation.

Mexico raised interest rates even less, by 7%, but unemployment actually declined by 4% (down to 2.7%), and inflation fell by 45%, ending the year with Mexican inflation at 4%.

Again, all these countries raised interest rates some, saw inflation fall by around 50%, and experienced mild changes in unemployment.

Europe

Most European Union members have the same currency, the Euro, and therefore have a common monetary policy. For us, that means they all experienced the exact same increase in the interest rate from 2.5% in 2022 to 4.5% by end of 2023, which is a dramatic 80% increase.

The effect on unemployment, however, is not uniform at all. Across the EU, on average, unemployment fell by 3% which means labor markets tightened and yet inflation fell by 74%! The EU ended 2022 with 9.2% inflation and ended 2023 with only 2.4% inflation.

Diving into specific country experiences, we start with Germany. Unemployment rose by 7% and inflation fell by 60% while in France unemployment rose by only 1% and inflation fell by 41%.

But, lest we start thinking of the Phillips Curve again, in Italy unemployment didn’t change at all, yet inflation fell by 94%. By the way, I double checked Italy’s inflation number, just to be sure. It was 11.63% in December 2022 and only 0.67% in December 2023. That’s a huge change and yet there’s no change in unemployment at all. And, in Spain, unemployment fell by 5%, while inflation fell by 44%.

Switzerland and the U.K. are not part of the European Monetary Union. They have their own currencies and own monetary policies as well. The Swiss raised their interest rates by 80% as well, although the raw numbers are important since it only meant raising interest rates from 1% to 1.75%. Nevertheless, it saw zero change in unemployment – like in Italy – and still a 50% fall in inflation (from 2.8% inflation to 1.4% by December 2023). The U.K. isn’t even in the European Union at all anymore, but I left it in the broad category of Europe, only raised interest rates by 50%, unemployment rose by 14% and inflation also fell by 63%.

Central Europe

Now that we know what to look for, let’s start a little backward this time. Inflation in all these countries fell by about 50-60% over the year. They ranged from 16% (Poland) to 25% (Hungary) at the end of 2022 and fell by about half to a range of 6.6% (Poland) to 7.9% (Hungary).

What sort of unemployment “drove” that lower inflation? Well, it’s not so clear. Hungary, where inflation fell the most (-68%), also saw the biggest increase in unemployment (+10%). But, we see similar inflation declines in other countries, and their unemployment rates fell by 4-5%. That means labor markets tightened in all those countries, but they saw similar drops in inflation. That doesn’t make any Phillips Curve sense at all.

Unlike most countries in the world, all these countries lowered interest rates over the year! Looking at the average for the region, interest rates were cut by 9%, unemployment fell (i.e., improved) by 1% and inflation still fell by 60%.

In case you are wondering why they cut interest rates, a quick check of the GDP growth numbers explains it. GDP growth fell in the Czech Republic to -0.7% and to -0.4% in Hungary. Those interest rate cuts are likely efforts to stave off recessions[2] in those countries. Romania still has 1.1% GDP growth, hence no interest rate cut.

Poland is a bit of an outlier here. It has 0.5% GDP growth (i.e., positive growth) but still cut rates by 15%. That might be because GDP was growing at 4.1% in 2022. In that case, policy makers may have tried to pre-emptively stimulate the Polish economy as they watched growth slow all year. In any case, the drop in interest rates with inflation still over 6% in all those countries does not bode well for next year. Expect continued inflation and slowing economic growth in the region.

Pacific Countries

Japan is just an outlier. No change in interest rates. No change in unemployment. Inflation dropped by 30%. As usual, the Japanese economy just seems like a different beast altogether. There’s no point looking in Japan for signs regarding Phillips Curves, their absence, monetarism, fiscal theories of the price level or any other textbook explanation.

The rest of the region seems to follow textbook Phillips Curves to some extent. Interest rates rose by 8% (S. Korea) to 29% (N. Zealand). Unemployment generally rose (except in S. Korea) and then inflation fell by about 60%. If I calculate the averages without Japan, then, on average, interest rates rose by 24%, unemployment rose by 7% and inflation fell by 27%. So, on average, the Phillips Curve mechanism at least appears to be present.

In all honesty, the economic performance in the Pacific region, less Japan, is basically what everyone expected to see everywhere, including me. We generally expect higher interest rates to tighten economic conditions and pull inflation down. That can be reflected in higher unemployment too, no problem. The problem is that the New Keynesians insist that the Phillips Curve mechanism must work, and is they key driver of inflation. It’s literally the central equation in their models for inflation[3]. But I’m not convinced at all that it should be.

Latin America

Latin America is a sad case, really. The people of that region have struggled with bad governance and bad policies for a long time.

Argentina’s government is bankrupt and inflation is around 161% today. It rose by 70% over the last year (from 95% in December 2022). They raised interest rates by 43% (from 70% to 100%) – arguably, I suppose – to fight inflation. Unemployment fell by 20% to 5.7% which is better than it is in most European countries actually (Spain has 12% unemployment, France 7.4% and the EU average is 6.5%). But Argentina is collapsing economically and politically. In the fall, Argentinians elected Javier Milei to be the new president precisely because the central bank and government generally seem to have messed up the economy so badly.

Chile and Brazil have been facing similar struggles, just on less grand a-scale. Inflation is now down around 4.7% in both countries. Unemployment is falling, and today they are cutting interest rates already. This is likely because GDP growth is slowing, although still positive in both countries. It seems like a mistake to me. As in Central Europe, I suspect that we’ll continue to see inflation and weak economic growth over the coming year.

Conclusions

Inflation has fallen around the world. Many people call it “immaculate disinflation” precisely because, as I hope you can see, it’s not 100% clear why it fell everywhere.

We can’t say it was the war in Ukraine that drove up prices and now they’ve fallen. The war rages on there, and has actually worsened in many ways. Since October we’ve also seen war in the Middle East.

Interest rates rose in nearly all countries. In all fairness, interest rates started rising in 2021, so they didn’t rise by as much in 2023 in many countries (e.g., the U.S.), because they were already near the end of their rate hiking cycle. I do think there are long and varied lags in the effects of monetary policy on inflation. Some of that is seen in these numbers where inflation has been falling all year because of the interest rate increases in the previous year. So, I don’t want to poke too much fun at our economic models and financial commentators. But still, the data doesn’t seem to support some unemployment-inflation trade-off that’s the key driver of inflation.

All that being said, once again, Welcome to 2024! It looks like we’ll see less inflation this year than last. That’s a good thing. We should expect some interest rate cuts over the coming year, which would be nice as well. How soon, how big, and how many cuts will be determined by GDP, unemployment, and inflation. If inflation gets near or below the target of 2%, and GDP growth turns negative at all, we’ll see bigger rate cuts and see them sooner. If not, then we won’t. Pretty simple.

Thank you for reading!

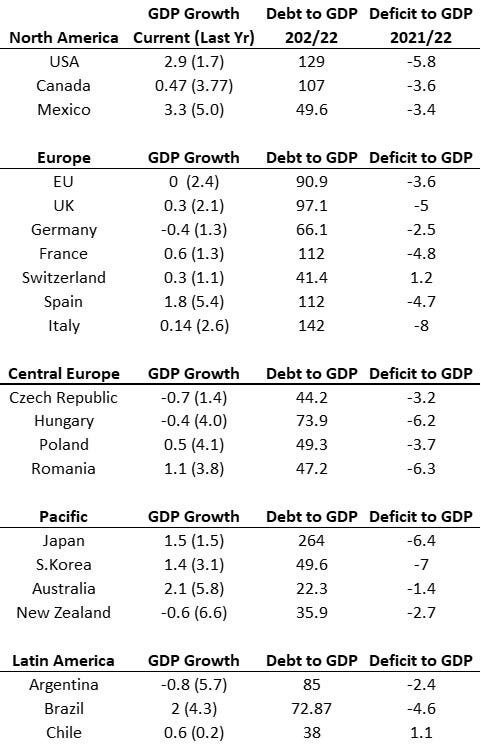

DATA APPENDIX

Table 1 is the complete table with interest rates, unemployment and inflation but I include all the numbers. Table 2 is GDP Growth, Government Debt to GDP and Government Budget Deficits to GDP. I didn’t discuss them because it’s hard to get fresh data across multiple countries. You’ll notice that all of those numbers are from 2021 or 2022. So they don’t pick up what happened in 2023. I’ll have to do a separate report about this topic but I thought some of you might be interested. Also, I truly believe government financial problems will loom large for us in the coming years. It’s a topic to watch.

TABLE 1

TABLE 2

[1] All my data for this column was obtained by hand from Trading Economics at the end of December 2023.

[2] In case it dawns on you at this point: Yes, that the interest rate changes we’ve been looking at didn’t cause much change in unemployment anywhere in the world should leave you questioning the effectiveness of lowering interest rates to stimulate an economy. While I’m focusing on the unemployment-inflation trade-off, it’s also true that interest rates seem to have had a smaller effect on the real economy generally.

[3] By this, I mean that the Phillips Curve equation is the core mechanism in the economy in their models. That they happen to combine it with interest rate rules to target inflation is neither here nor there. They could explore a range of monetary policies if they want like fixed exchange rates, money growth rules, and the like. In all those cases, they’d still have the Phillips Curve at the heart of the inflation-generating process. It emerges naturally when you assume Calvo pricing in these models, so if we want to point past the Phillips Curve, we could point to Calvo pricing. But the Phillips Curve is the one getting all the public attention and hence my focus here.

Thanks!

100% Peter. I already drafted my next piece (hope to release next week) on why we all feel so bad even though inflation and other econ numbers improved. All exactly to your point.