The Positive Case of Switzerland

We all know that every country is facing the same economic challenge today. It’s a global problem. We all have high inflation, high debt and looming recessions. Right? Well, no. Not so fast…

This column takes a look at in Switzerland where inflation and debt are low.

Photo by Florian van Duyn on Unsplash

Switzerland is interesting because it’s in the heart of Europe but it isn’t a member of the European Union. That means the Swiss face most of the same economic conditions as other Europeans but don’t deal with the bureaucrats and politicians in Brussels or use the Euro. The Swiss have their own currency, the Swiss Franc, and therefore determine their own monetary policy. We want to look at policy differences the Swiss and other countries to see whether these mattered for Switzerland’s current good economic numbers.

The Swiss in Demographic Context

Let’s start with some basics about Switzerland.

First, it’s in the center of Europe geographically, historically, and culturally. It’s a European country in nearly every regard. It just didn’t choose to join the European Union (region of countries with various shared benefits) nor the Eurozone (countries using the Euro) and has always maintained some independence from Europe politically.

Within “Europe”, it’s most similar to Norway in terms of GDP per capita and closest to Austria in population. Switzerland, Norway and Austria are all among the wealthiest countries in Europe as measured by GDP per capita.

To put Switzerland in broader context, I include the EU, UK and USA[1]. This just gives us a sense of the relative size of the country and it’s economy.

The Swiss in Economic Context

Given that Switzerland is in the center of Europe with a common European economic experience, we’d expect Swiss inflation, debt, and so on to be similar as well. They are not.

At 3%, inflation in Switzerland is much lower than any in any of its peer countries. Although 3% is low, it is still higher than the Swiss central bank’s target for inflation which is 2%. Consequently, the Swiss central bank has been raising interest rates recently to fight inflation. In this regard it’s at least one similar challenge but the magnitude is totally different. Getting inflation from 3% down to 2% is different from taking it from 7-11% down to 2% which is the challenge facing most other central banks today.

Norway turns out to be an interesting country for comparison because, like Switzerland, Norway also has its own currency, the Norwegian krone.

Norway and Switzerland can both conduct their own monetary policy independently of the European Central Bank (ECB) which controls the Euro for all the Eurozone countries (including Austria). The question here is whether that has allowed them to keep inflation under better control.

Norwegian inflation is high. Swiss inflation is not. Norway in this regard looks more similar to the rest of Europe than to the Swiss albeit with slightly better results than the Euro Area members.

Monetary independence alone did not seem to help Norway keep inflation in check.

What did the Swiss do differently?

Government Spending

A country’s currency is only as strong as the government that issues it. But how a country’s government finances per se are perceived is very hard to measure. That’s one reason why Norway and Switzerland can have the same debt to GDP ratios, but it doesn’t necessarily mean they both have the same inflation rate. Looking at debt to GDP ratios to understand inflation turns out not to be too helpful.

Alternatively, we can look at what the countries did with government spending in recent years. This is not a question of long-term fiscal responsibility but rather of how much stimulus they pumped into their economies and whether it mattered for inflation.

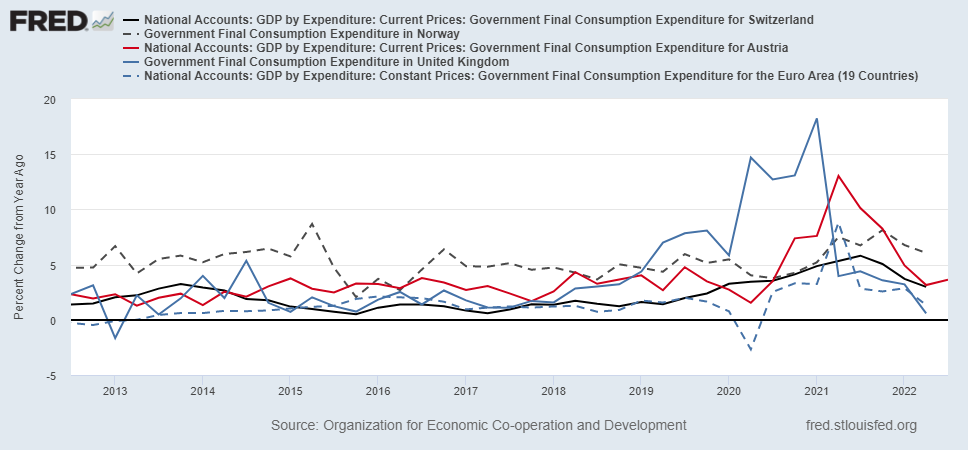

The following graph shows one measure of government spending for Austria (red line), Norway (dashed line) and Switzerland (solid line). Of the three, the Swiss increased spending the least during the Covid period of 2020-2022.

Peak Austrian spending increased by about 13% year-on-year while it only hit about 8% in Norway and 6% in Switzerland[2]. If government spending over stimulates the economy and generates inflation, then we’d expect inflation to be highest in Austria, next in Norway and then lowest in Switzerland. And that’s what we have: Austrian inflation is 11%, Norwegian is 7.5%, and Swiss is 3%.

We can’t compare against the Euro Area overall since the Euro Area doesn’t have a single fiscal government and hence has no meaningful government expenditure at the Euro Area level. Nevertheless, there is an average measure of all the Euro Area countries’ government spending. Adding UK spending too and we get the following graph.

The highest increase in spending was in the UK (solid blue line), peaking around 18% while the average Euro Area increase was lower, peaking at 8.8%.

If government spending is a significant driver of inflation, then again we should see UK inflation highest (it’s 11.1%), Austria second (it’s 11%), Euro Area third (it’s 10.6%), then Norway (it’s 7.5%) and finally Switzerland (it’s 3%).

The fact that it lines up suggests that spending plays a role. The fact that it lines up perfectly, however, is likely just due to chance and hence isn’t as meaningful. Please don’t read too much into that. We wouldn’t get such a perfect prediction if we included more countries. For example, the US spending increase peaked at 49% but US inflation (7.7%) isn’t the highest in the group. But the general trend does matter and suggest higher government spending has been a factor driving inflation today.

What then is one thing Switzerland did differently? It didn’t increase government spending. That looks like it mattered.

The other factor we would expect to be a serious driver is the growth rate of the money supply. We turn to that next.

Monetary Policy

Traditional economic theory argues that inflation is “too much money chasing too few goods”. So, for the same amount of goods, if the government printed too much money, that should drive prices up. All else equal then, countries printing money at a faster rate should see higher inflation than countries printing money at a lower rate.

Austria is a Euro Area member and doesn’t have its own currency. So I removed it. But we can look at Norway, Switzerland, the UK and the Euro Area overall.

Again, the details are less important than the big trend which is that Switzerland (solid black line) printed money at a rate much lower than any of the other countries.

The ranking in terms of money growth is as follows: Norway (14.4%) > UK (12.5%) > Euro (11.9%) > Swiss (7%). And inflation is UK (11.1%) > Euro Area (10.6%) > Norway (7.5%) > Swiss (3%). The trend suggests that countries that printed a lot of money over the last two years tend to have higher inflation today.

This means that the two classical predictors of inflation, government spending and printing money, were both better managed in Switzerland than in the other countries and it looks like that has meant lower inflation today.

That is meant as a positive economic lesson for voters and policy makers around the world. To quote a popular American sign in neighborhoods: “Drive Slowly. Drive Like Your Kids Live Here.” The implication being: drive slowly and cautiously so no one gets hurt. We should buy these signs for politicians and central bankers to hang in their offices.

The Energy Crisis

There are two other common targets of blame for today’s inflation woes: supply chains and energy.

There is nothing that I know of that is unique about Switzerland and global supply chains. Therefore any supply chain shock in the world, especially in Europe, should be common to Switzerland as well. We don’t have special, country-level indicators that are reliable and nothing seems to show up in the data elsewhere. So, I’ll ignore supply chains. Including them, in any case, would only strengthen my case that the Swiss better managed their affairs since the shock is common across Europe but Switzerland performed better.

Energy should also be similar in Switzerland and the rest of Europe but potentially worse in Switzerland since it’s a landlocked country. The graph below compares energy prices.

The mix of countries is a little different because comparable data isn’t available for all the countries we were looking at and I wanted to include France. That being said, the main trend is again quite clear: one country is radically different. This time, however, that country is Norway.

That Norway is the outlier with an unusually high peak increase in energy prices (an over 80% annual increase!) is surprising on two counts. First, Norway is a major global oil producer and this just reminds us that “energy” is not just oil. And, in many cases, it’s the non-oil energy prices like natural gas prices that are problematic today. Second, IF energy prices were a major driver of inflation, Norway should stand out for having much higher inflation but instead has 7.5% inflation which is bad, but better than all the other countries, other than the Swiss.

Our focus is on Switzerland, however, and the important point is that it doesn’t look that different from the rest of the European countries. It is admittedly the lowest line (solid black) but with Norway reminding us that this isn’t likely the key driving factor of inflation, it’s hard to argue that we should read much more into it.

The Swiss energy industrial base does have some advantages that are worth mentioning. Due to the country’s relatively few domestic natural energy resources (oil, natural gas, etc.), it is heavily reliant on hydroelectricity (59.6%) and nuclear power (31.7%) for electricity production[3]. That is different from most European countries other than France which also uses nuclear.

It turns out that this mixture of energy production is also more environmentally friendly. Switzerland has per capita energy-related CO2 emissions that are “28% lower than the European Union average and roughly equal to those of France.”[4]

France also uses nuclear power as a major clean energy source. And, indeed, France’s energy price pattern (dashed black line) is similar to Switzerland’s and both are clearly below that of the Euro Area average (red line).

Inflation in France, at 6.2%, is also lower than the Euro Area average, but still double that of Switzerland. The conclusion might be that wise energy policy helped offset the energy price shock of the Russian war in the Ukraine. To the degree it feeds into overall inflation, this helps explains Switzerland’s low-inflation success and France’s similar but limited success within the Eurozone.

If France also had its own currency, kept the rate of money growth low, it too might only have 3% inflation. But then again, we can never know.

Switzerland’s Policies Should Give Us Hope

This column looked at Switzerland as a success story. I tried to focus on the sorts of policy differences in Switzerland that seem to have mattered in keeping inflation at bay. And they are all things other countries like the US, UK, and the rest of the Euro Area (as well as the rest of the world) can do too: moderated government spending and much less money printing. Seems simple.

The Swiss survived Covid but with less economic turbulence and today they have lower inflation. The government spending and money blowouts we saw in other countries – including my own – look more and more like the culprits of today’s economic woes.

Let’s make signs and send them to our politicians and central bankers for their offices: “Conduct Policy Like Your Kids Live Here: Slow Down, Proceed with Caution”. The Swiss example shows its possible.

[1] Please note that the population estimates are different years, but GDP and GDP per capita are generally 2022 estimates. That is to say, you can’t divide this GDP number by the population and get the exact GDP per capita in the table. This is just to give you a general sense of where Switzerland is comparatively speaking. The precision of the numbers is a bit less complicated.

[2] In the US, by way of comparison, the peak was 47%. Then a year later we did 46%.

[3] Those numbers come from Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Energy_in_Switzerland

[4] Quote and is from Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Energy_in_Switzerland