Photo by Grace Galligan on Unsplash

Who would have guessed we’d be here? No one. That’s who.

No one imagined that we’d have the very strange and dangerous set of affairs we face today. I don’t have the answers, but I can share some thoughts on the economic implications of some of these things, and, more importantly, share what I’m watching for.

I think I’ll attack these in reverse order. Debt is possibly the most straightforward – at least it’s the most predictable –, then inflation, and, finally, geopolitics/war is the least clear.

U.S. Government Debt

Government debt is too high and growing in the United States. That is now and will be a global financial problem.

In normal times the U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed) buys a lot of the government’s debt, Japan does the same as they stockpile U.S. debt as foreign-currency reserves, and China was doing the same as well. In the current, non-normal times, the Fed is selling debt. This is generally referred to as “quantitative tightening”. Japan and China are buying much less.

During the Great Financial Crisis of 2008, the Fed engaged in quantitative easing as a way to continue expanding the money supply after it had already pushed interest rates essentially to zero[1]. While it did buy bad mortgages from banks and so on, a lot of what it bought was U.S. Treasuries. That is, U.S. debt.

Quantitative Easing Explained

“The” short term interest rate is “the price of money” and, normally, when the Fed expands the supply of money, “the price of money” falls. But in the 2008 crisis, policymakers pushed supply out so far that “the price of money” essentially hit zero[2]. Nevertheless, they wanted to buy more assets from banks (which increases the supply of money) and lower long-term interest rates (another “price of money”) to further stimulate the economy. To do that, they bought longer-term bonds and assets from the banks and the U.S. government. That was all called “Quantitative Easing” (QE), because it was easing (i.e., expanding) the quantity of money in the economy.

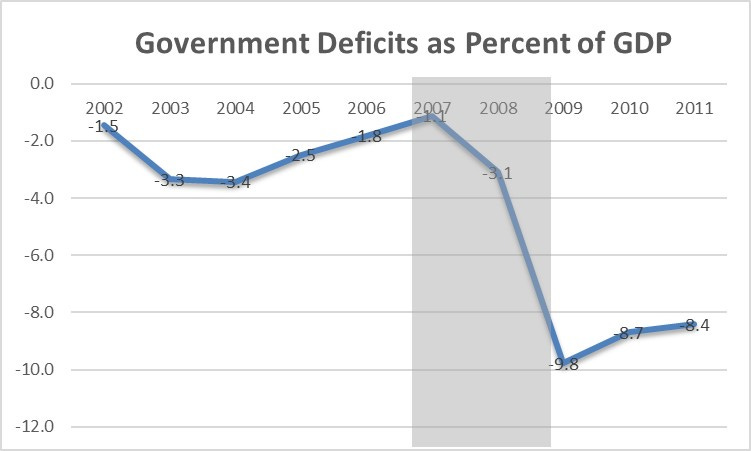

The Fed’s borrowing didn’t directly cause the U.S. government to run larger deficits, but it certainly made it easier for the government to do so for two reasons: first, with interest rates near zero, the cost of borrowing was lowered to near zero, and, second, the U.S. Treasury knew there would always be strong demand in the market for U.S. debt, because they Fed was gobbling up the stuff like a starved animal[3]. The government ran the largest non-wartime deficits in history (at the time). From 1962 – when I have CBO data – until 2008/2009, the highest ever was 5.9% in 1983. Normal deficits were around 2% of GDP and anything over 3% used to be considered dangerous and unsustainable.

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

Over the coming years, the Fed maintained its balance sheet of assets, which meant it rolled the debt over as it expired, and was therefore a constant presence in U.S. debt markets, buying government debt for the next 10 years. In 2013 the Fed publicly announced it would slowly not-replace the debt, which meant slowly shrinking its balance sheet, “tapering off” its purchases. The mere announcement of this idea was so scary to market participants that they panicked and we had what was called “the Great Taper Tantrum of 2013” in financial markets. The Fed had to intervene to prevent the interest rate spike in bond markets, and calm investors’ worried minds.

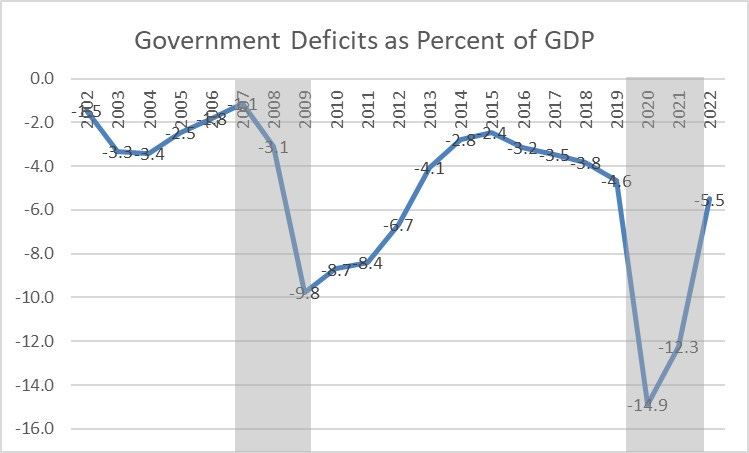

It returned to the plan by 2016, and you can see it slowed from there until Covid hit and…WHAM! … and the Fed bought more assets and the government borrowed more money than anyone ever could have imagined.

You can see the plateau around 2014 that caused the “Taper Tantrum” and the slow decline in 2016, followed by the spike around Covid in 2020. The Fed continued buying for the next two years but rising inflation convinced the Fed that it needed to raise interest rates and finally tighten the money supply.

Throughout that period, the Fed was once again the proverbial 200 pound gorilla in the government bond market, buying up as much as it could. Additionally, both China and Japan were the first and second largest international purchasers of U.S. debt as they filled up their international reserve coffers.

Global banking regulation had always required banks to hold “safe assets” and the U.S. debt is considered the “safest asset” on Earth, even called in financial circles a “risk-free asset”. Again, following the Great Financial Crisis, global banking regulation went into overdrive, dramatically ramping up the need for all banks around the world to hold more “safe assets”. That is, all banks in the world began demanding more U.S. debt.

From the Fed, Japan, China and all global banks, the U.S. government had a nearly captive audience demanding all the debt it could issue.

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

The U.S. government did not complain, and our representatives in D.C. spent like the reckless drunken sailors that they’ve shown themselves to be. And, as if wanted to prove to us that they are indeed behaving like drunken sailors, below is the U.S. Government’s own Congressional Budget Office’s projections of deficits and debt based on current official budget plans, as of June 2023.

Source: U.S. Congressional Budget Office, “The 2023 Long-Term Budget Outlook”, June 2023.

I’m sorry, but that’s just absurd on its face. Somehow it reminds me of all the startup companies I met over the years who showed me their projected financials. Today we have no money. But next year we will sell $500,000, then $10 million, then in 5 years be a $1 billion company. Really? Wow! Sign me up!

My late friend, Professor Matt Rafferty, used to use the South Park Underpants Gnomes episode for this kind of a story. Google “South Park Underpants Gnomes”. The main characters encounter garden gnomes stealing their underpants from their rooms. When asked why, one gnome explains that “stealing underpants is big business!” They follow him to a private bunker where he shows them a giant pile of stolen underpants and explains the business plan: “Phase 1: Steal Underpants.” … silence…“Phase 3: Big Profits”! The joke is that they of course have no phase 2. Our U.S. government is saying: Phase 1 is Spend Big and Run Massive Deficits. … then err… Phase 3 is great prosperity for all! Uh….okay.

This is not feasible. U.S. Debt today stands at 129% of U.S. GDP. And our own government projections see it skyrocketing from here? It won’t happen, and the drunken sailors will find out soon that they’ve run this ship of foolishness into the ground. The Fed is buying less. China and Japan are buying less. And other investors can see the bad financial writing on the wall.

The U.S. Fed has been unwinding its balance sheet for about a year. You can see in the earlier FRED graph (above) that the curve starts declining at the end. The blip up, by the way, was around March this year when they intervened after the brief banking panic this Spring. But it was a blip in an otherwise continuous decline that is expected to continue. How long? No one really knows.

It is not clear what level of assets the Fed wants to target. There’s a lot going into that decision based on our current “Ample Reserve Monetary Framework” that’s beyond the scope of this current column. But for now, the decline will continue.

We’ll hear a lot more about this over the coming months. In recent weeks, financial news has been full of speculations about why long-term treasury interest rates were rising dramatically. Some of that is definitely due to weak demand for them. At the same time, over half the U.S. debt is relatively short term and our Treasury Secretary explained they will be scheduling to refinance about 11% of U.S. GDP in debt over the coming 6 months. That’s a tremendous amount of debt and refinancing today will be at the highest rates in over a decade. And the U.S. Treasury has decided to convert that short-term debt to longer-term debt of 10 and 20 year durations, just to lock those high interest rates in for many years to come.

You would think that high interest rates would dampen our collective appetite to push our politicians to spend and borrow more, but you’d be wrong. So far, rather than tap the breaks this year, we’ve aimed our ship for the rocks. On October 20th the U.S. government posted a $1.695 trillion budget deficit for 2023 which is a 23% increase from last year. With a GDP of about $25-27 trillion, that’s another 6% or so government deficit and we aren’t in a recession or anything of the sort today.

Everyone is worried about how they will finance this. Who will buy that debt? Who will be on the buying side as they refinance 11% of GDP (another $2-3 trillion in debt) over the coming 6 months?

Is the world going to end? No. But rates are rising on these debt sales, and I believe that’s a sign of both a high rate period and, more importantly, a growing recognition that this is not sustainable, and hence there’s an ever softening demand for U.S. debt.

This will be a major financial problem, and a major political topic for Americans over the coming year or two, especially as we enter a presidential election year.

Inflation

The above debt issues are not independent of the inflation challenge we face in two regards. First, high interest rates to fight inflation make the debt problem more urgent. Second, the continued massive government deficit spending continues to overstimulate aggregate demand in the United States, countering what the Fed is trying to do and hence puts strong upward pressure on U.S. inflation. It directly fights the Fed’s anti-inflation policy.

U.S. inflation is currently at 3.7% which is good after 9% a year ago but it’s still isn’t near the 2% target. Fed Chair Jerome Powell said on November 1st “The process of getting inflation sustainably down to 2 percent has a long way to go” (November 1, 2023, Press Conference) and current Fed forecasts of U.S. inflation are that we only get to 2% in 2026 (See footnote[4] ). So, we have a way still to go with high interest rates and quantitative tightening.

Only a few months ago we were all worried that that high interest rates would drive us into a recession. I was convinced of that for sure. It didn’t happen and the economy even seems to have sped up, hitting a 4.9% growth rate in Q3 driven largely by a surge in consumer spending. Unemployment also remains below 4%, widely considered the long-term unemployment rate for the United States.

That is all a head scratcher, to be honest, and the suspicion is that it’s government spending propping things up.

This past Friday’s job report showed that might be the case. Employment increased by 150,000 jobs in October which is strong, but below what everyone expected (BLS link[5] ) and unemployment ticked up from 3.8% to 3.9%.

But, what caught my attention was that of the 150,000 jobs, 51,000 (34%) were government jobs and another 19,000 (13%) were Social Assistance. Social Assistance includes things also heavily funded by government like personal and home care aides, social and human services and also child care workers which continued to receive huge government subsidies from the pandemic that are just ending now. The point is that government and social assistance accounted for 46.7% of the new jobs in October. That’s not really a foundation for a robust, vibrant and innovative economy.

The next 58,000 (39%) jobs were in Health Care. Ambulatory health care services (32,000), hospitals (18,000), and nursing and residential care facilities (8,000).

That means government, social services and health care accounted for 128,000 of the 150,000 jobs in October. That’s 85%. Those are all either government explicitly or heavily-government-determined sectors. That worries me.

Traditionally, private sector areas are manufacturing and construction. Manufacturing shrank, possibly due to the autoworker strikes. Construction did grow but the massive government infrastructure bill is still feeding that industry.

I have deep concerns that the GDP growth and low unemployment is not real. It’s government created, and hence part of the growing balloon of spending that’s going to pop and cannot be sustained. And, all this government stimulus pushes demand higher and faster than it should organically grow, likely causing more inflation, and requiring the Fed to raise rates more to fight it. That moves us into a nasty debt-inflation-interest rate spiral that will not end well. Historically those episodes end with massive austerity packages of extreme government spending cuts and tax hikes along with deep recessions to readjust the macroeconomic balance. Let’s hope things improve before we reach that point.

Geopolitics and War

Gee, nice way to end on a light note. Ugh. Sorry. But it must be addressed. Interestingly, I can address this the most quickly.

It is not clear what war means for economies. As an economist, let me state as I did about the Ukraine war, that economists measure “well being” by individuals and households getting what we call “utility” (i.e., “well being”) from pursuing the things they value. No matter how we measure it, many people in the world today are dying due to war, and more will continue to die until these wars come to resolution. That is unambiguously bad no matter how you look at it, and any modern economic model with individuals maximizing utility (i.e., nearly all modern models) will show the same result if lives lost are accounted for, as they should be.

Now, from a financial/economic point of view, which is what most people have in mind when they ask about “the economic effects”, I can say a few things. First, some industries, like those producing military and related equipment, will benefit. That may also be true for industries supplying humanitarian aid. But, keep in mind that those resources come from other, alternative uses. That means less resources (financial, human and other) going into more productive and beneficial uses. That will slow developments in other areas where we might otherwise be inventing new technologies, goods, and services to support human flourishing and well-being.

The broader global malaise suggests a deeper problem. I see a slow pulling apart of the fabric of global cooperation. Wars, shifting alliances, sanctions, tariffs, and all of these things raise the costs of trading with each other around the world. Economists view trade as the way we cooperate with each other to achieve things.

Wars, regulations, more restrictions and the like all make it harder to cooperate. And we can already see how the Russian War on Ukraine and the Hamas War on Israel are causing global partners to turn on each other, pick sides, and separate. I predict that all of this will raise the cost of global trade and all forms of global cooperation. It will slow global GDP, decrease human flourishing and well-being, and raise the costs of nearly all goods sold making life harder for those least well-off in the world.

Additionally, the major governments of the world are all facing similar financial strains as the U.S. government is. That means, to support war efforts, they will borrow more, and this too will push up inflation and over stimulate demand in certain industries.

Oddly, the U.S. is still the safest haven. So, there is also the odd - and actually pretty good - chance that as global investors seek safe investments in these increasingly dangerous times, demand for U.S. debt will rise, undoing the pressure campaign on U.S. debt and deficits that I discussed at length above. I do not view that as a good thing because I think that the current pattern of spending and borrowing needs to end, and sooner rather than later. But politicians will misunderstand (or spin) this to be support for their programs and spending and “market support” for U.S. government financial management.

Conclusion

To close, debt is a bad and growing problem. But, I see many forces running that ship onto the rocks, which I hope slows the spending and deficits, encouraging some realignments before we face a true economic crisis.

Inflation is coming down around the world and in the U.S., but the continued fiscal stimulus pushes inflation back up, and the fiscal spending problems could cause higher inflation for other reasons as investors question governmental ability to repay. So, it’s a tug of war between central banks and their interest rate hikes slowing inflation, and governments pumping money and speeding up inflation. Currently the central banks are winning.

The wars in Europe and the Middle East are pulling the world apart and making all forms of cooperation more difficult around the world. That has the potential to push all countries to re-shore production, cooperate less with other economies, and overall decrease the scope for improvement worldwide. That could usher in a long, cold economic winter with higher costs.

Thank you, as always, for reading.

[1] To understand why this is a necessary process. For the Fed to add money to the economy, it must purchase something. Traditionally it would buy U.S. Treasuries. By purchasing, say, a $100 bond from a bank, it removes the bond from the bank and gives the bank $100 cash (technically reserves, but we can think “cash”). The bank can then lend that out or whatever. And… that’s how the money supply grows in an economy.

[2] In policy, financial and academic economic circles, this phenomenon is referred to as “hitting the zero lower bound” because the assumption was that you can’t push the price of money (interest rates) below zero. Then Europe and Japan proceeded to have negative interest rates. So the it’s not clear that zero is a real lower bound. The Bank of Japan’s official policy interest rate is still -0.1% today on November 6, 2023.

[3] We can’t completely claim causality, however, because the U.S. government was also trying to stimulate the economy during a time of economic crisis. It would have spent more, taxed less and run deficits anyway. The Fed’s actions just made that less costly to do.

[4] https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/fomcprojtabl20230920.htm

Thank you very much for these deep insights. As always a great pleasure to read. Unfortunately i share your opinion of being in a ship sailing towards rocks. Hopefully the captains will realize that as well in time, before its too late....