Water 4 Mercy

Nermine Khouzam Rubin’s eyes beam and she literally bubbles over with enthusiasm when she talks about bringing water to African villages. Doing this in a sustainable way that builds an ecosystem for further human flourishing has become her mission in life.

I caught up with Nermine recently in New York, and sat with her for an interview. Her story is inspiring to me personally, and I hope to you as well.

In addition to her story, I was very interested in the unique steps she’s taken to make her project “economically feasible”, and how she intentionally overcame some of the traditional hurdles we face in the realm of developmental economics.

An African Learns the Very Hard Lesson of Development Economics: Unintended Consequences

“I’m an African,” Nermine tells me. “I was born in Egypt and moved to the U.S. at a relatively young age.” Her family left the region after the 6-Day Arab-Israeli war and found their way to the United States. She still speaks Arabic and French, but English has become her mother tongue as she established a professional and personal life over the years in the U.S. She lives today in Florida with her husband, Les Rubin whom I’ve mentioned in other columns[1].

In 2017, Nermine’s daughter traveled to Africa as part of a study-abroad experience in college. Having long wanted to visit orphanages and programs they supported, Nermine flew to Africa for a special mother-daughter trip to see the orphanages and meet local church leaders.

In Tanzania they had the chance to meet some of the children they had been helping through their church. “It was thrilling,” Nermine explains. “I was so excited to see the good we were doing with our donations, to meet the actual people we were helping.”

One young girl invited Nermine and her daughter to visit her village and meet her family. They jumped at the chance, and rode off in a jeep three and a half hours outside of Dodoma, Tanzania’s capital. The village they found was little more than some mud and clay huts in an otherwise desolate area.

“As we pulled up, we could see all the men sitting around, smoking, drinking and doing nothing. It was 2:30 in the afternoon. I couldn’t believe it! We entered their two-room mud hut and the girl’s father came over, overwhelmed with gratitude, then her mother and siblings invited us in, all dressed in their best clothes,” Nermine continues. “They invited us to their home, and the whole family crowded in to meet us. They were so very nice and appreciative, but a nauseating feeling began growing in my stomach.”

She explained that the money they sent did help some, of course, but otherwise taught the whole family and whole villages of families how to genuflect to their visiting cash sources. They all had learned to “kiss the hand of the white woman to get their money”, she explained. It made her sick. “I saw the unintended consequences of our efforts to help. We were enabling them not to have dignity. I wanted to help them have dignity and our money was doing the opposite.”

“At the time I was very upset at the men in these villages. I saw them doing nothing. They hung around, smoked, and drank. I thought they were lazy and loafing off the women. The women and children walked for miles to get water and had little time for anything else. The kids didn’t have time for quality education, and their prospects were to hang around smoking, walk to get water, and learn to bow for the visiting Western donors. I was horrified and vowed to change this. There had to be a better way.” Nermine was animated yet intensely stern as she explained this to me.

She had learned a lesson all too familiar to those of us interested in development economics. Many, many well-intentioned economic development projects have actually made matters worse for the locals they sincerely intended to help.

By giving money for the girl’s education, the family rationally allocated their time to pleasing donors and getting more money. Investing in that meant investing in some nice clothes and pleasantries to host the guests, spending time getting to know the donating agencies, and getting on lists for handouts. Surely some people make something out of these opportunities, but, more often than not, it also leads to dependency.

When other well-intentioned do-gooders decide to build a school or launch some large capital project, the local economy is then left unable to maintain it. It falls apart over time. Local resources are re-directed to try to maintain the school or project. But, what are those resources re-directed from? Something more immediately important for the local community? Children are pulled from helping the mother gather water, and other problems emerge because resources are re-allocated away from some uses and toward what the foreigners think the locals ought to do.

There are plenty of other examples where international groups donate food or other goods to a region and it collapses the local farmers market because people won’t buy local produce when they can get it for free elsewhere. Without an income, farmers leave their farms, and the local ecosystem is destroyed.

But what can be done? There are plenty of secular reasons we want to help those less fortunate. We’d like to see flourishing economies and flourishing people all over the world. They make great friends, allies, trading partners, and the like. They produce new technologies and ideas as their human potential is unleashed. On moral grounds, I believe, as do many others, that those of us who are better off have an obligation – in my case a Christian-moral obligation – to help those less well off. But, how can we do that without making matters worse for those we intend to help?

Nermine believes she has found an answer. It starts with water, and the recognition that long-term sustainability must be locally driven, based on local knowledge, local interests, and with local ownership.

The Birth of Water 4 Mercy

After talking with the locals for some time and visiting other villages, Nermine realized that the local men were not lazy. They were in despair. They had tried and failed. Life was hard. They performed some local duties, and then literally had nothing else to do.

The problem was water. The only source of water for many villages was hours away by foot. Without a local, clean water source, people couldn’t develop anything.

Source: https://www.water4mercy.org/projects . “Maseya Village is home to 4,275 people. During the rainy season, the people rely on digging holes in the dirt along a river stream even though the water in contaminated, however when the dry season comes, the villagers are no longer able to dig holes, but have to walk close to 7 miles to get water.”

Without clean and accessible water, for example, their local gardens produced very little. Nermine soon learned, however, that the locals did own the plots of land they worked. They had legally recognized property rights over their houses and land that go back for generations.

Nermine believes that God then gave her the flash of insight that pulled it all together. She became convinced that she would figure out how to help the locals get water for themselves, manage it themselves, and then learn to build their own community the way they see fit to meet their own needs.

“I was a woman on a mission,” her eyes now flashing with determination. “I began learning about different organizations that help with water, and which arrangements work, and which ones do not. But people thought I was crazy, of course. Money had been donated to these villages for years with no change. What made me think I had the key? She pauses, reflects, then continues… But, Chris, I knew in my heart that these people could live and work with dignity. I just knew it.”

She soon partnered with Innovation Africa (IA), https://innoafrica.org/, which uses Israeli solar and water technology to build sustainable clean water pumps. IA is the most advanced in this field and has even received awards from the United Nations for their technology which is remotely monitored and updated in real time.

But, she quickly realized that, while the key first step, water was just that: the first step. She met with innovators and researchers at world renowned Hebrew University in Israel’s CultivAid to learn about agriculture, https://www.cultivaid.org. She met with Don Bosco, https://dbtechafrica.org/, an Italian-based, Catholic training organization that focuses on technical training for disadvantaged youth around the world.

She began pulling these resources together and connecting a consortium of like-minded organizations to help. In 2018 she founded Water 4 Mercy, Inc., https://www.water4mercy.org/home-old, as sort of an umbrella organization to bring the groups together to meet her vision for how to help. It also allows her to run a 501(c)3 in the U.S. through which she can legally raise and allocate funds.

In addition to bringing water, she wanted the local communities to own and maintain the water pump, and learn from the best in the world how to irrigate, grow crops and build businesses around the opportunities that the water would provide. And, she wanted it all done so that the locals owned and directed it to serve their needs, and so that they could find solutions that she and the others might not even imagine.

To make this work today, she brings in Innovation Africa to help build the water pump and establish a local community board to manage it. With CultivAid she bring in experts to teach the locals farming techniques that are appropriate for their local soil, water sources, environment and so on.

“Back in the States, I sold everything I could. I cashed in retirement accounts. I sold property. I basically cashed in everything I could … I was determined to prove that this ‘field of dreams’ works” she interjects, then continues, “until I could gift one million dollars to establish the first Agricultural, Innovation and Technology Center (AITeC) in Tanzania. Which I did.”

Nermine is inclusive. The AITeC she established, www.AITECFarm.com, is a joint project between CultivAid in Israel, Don Bosco’s office in Dodoma, Tanzania, and Water 4 Mercy in the United States. She beams with pride as she tells me all of this and I can’t help but think that no one would dare stand in her way. Actually, it’s better than that. She does it all with such love and passion that no one would want to stand in her way. Instead, you find yourself only wondering how you can help. I’m sure she would also say that God is working through and with her to get this done.

No governments, no agencies, no global elites are going to stop this woman who decided she’d seen enough of what the traditional methods delivered. “These people deserve dignity.” And, that is that, as they say.

The Results

As an economist, I wanted to know how it works. Why isn’t this just, yet again, some “American lady” coming in with her ideas of what the locals should do?

Nermine explains that water is universal. It’s the start of all life. There’s not Western versus African or other opinion on that. It’s a fact. So, it has to start there.

The solar powered pump brings fresh clean water directly into the center of town. It’s owned, managed and maintained by the local community, then monitored live, in real time. “But how do you get around the development problem of bringing in capital that the local community can’t support long-term?”, I asked. It turns out, that’s where the Don Bosco and AITeC partners come into play.

Once there’s water, everything else follows. The local women and children don’t travel for hours. The houses and land which have been owned by the locals for generations begin to flourish with the produce they can grow. And, other businesses immediately emerge.

“Chris! You can’t imagine!” Nermine smiles and beams with pride. “Now when I return to those villages, the men are working and proud. They have dignity.” She places her hand on my heart and continues, “They are proud to provide for their families and let their kids go to school, help on the farm and in the family business. They all have their own dignity. Women can be women. Men can be men. Kids can be kids.”

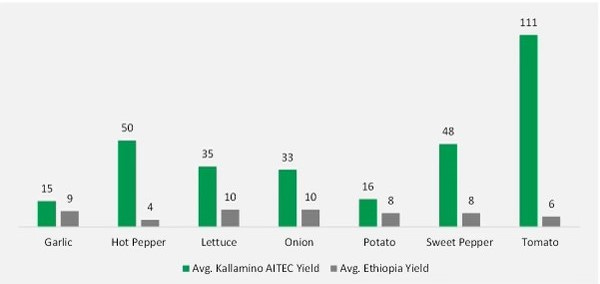

Source: Nermine. Green is the yield at her AITeC sites in Ethiopia compared to the average yields.

Crop production has risen dramatically and the people are healthier today than ever. Surpluses are traded and sold. The water allows the locals to start a range of businesses and to improve their own lives.

In addition to farming, Nermine told me about local brick businesses that emerged. With the extra water, they can make and sell bricks for their houses. That means, additionally, the houses look better and better every time she visits.

Because the crops and the businesses are locally owned, the locals get the profits. “Money is a huge motivator now, and they are all working hard to have a better life for themselves and their children,” she explained. The kids have better clothes that the families bought themselves with money they earned. No longer do they have to kiss a hand to get money. They earn it themselves in ways they see fit. This is human flourishing at its best.

Nermine explained how it all works. She raises money and helps coordinate. The water pump is the first step, and the locals form their management association to oversee it. Then comes the vocational training centers, each focused on helping build on local resources, talents, and so on. They then farm their own land for consumption and trade, and they get the proceeds. From there they form locally-owned businesses to solve problems they see, and to serve each other as they see their needs.

The whole project, from water pump to training center and crops, is generally self-sustaining within 2.5 to 3 years. That means they are self-financing and self-managed. To answer my economics question, the local economy grows enough by 3 years to maintain the capital it could not even have dreamed of acquiring before.

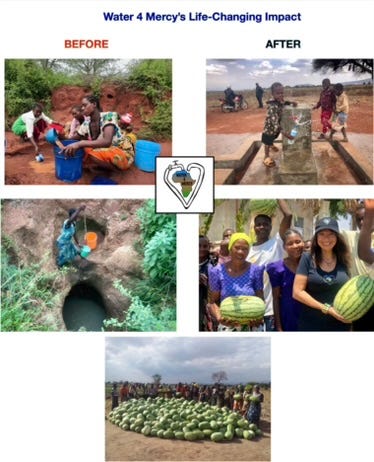

The first project in Tanzania was in the village of Mwinyi with 2,000 people. “Before we were able to provide the people of Mwinyi water, they were digging holes in the ground that were close to 50 feet deep! The water they were drinking was giving the people there water-borne diseases. We were able to provide 16 water taps throughout the village, which now has 5,000 people, more than double the original population. And the generous people of Mwinyi are even sharing their new clean water with the 2 surrounding villages.” Today, the people of Mwinyi are doing well. They proudly work, the families eat better and they are building a new life. They are building their own lives. They earn their own dignity with their own hands.

Today Nermine and team have water pumps and agricultural sites established in Tanzania, Ethiopia and Kenya with plans for Morocco and Uganda next. All of them have had the same success.

Asked what she’s doing now? Doing next? Well…no surprise: “I’m raising money and every dollar counts. I need about $100,000 for each village project. It’s about $65,000 for the initial water pump and solar technology then it’s about $35,000 for the agricultural training and inputs… we also have real time remote monitoring so we can ensure everything is working 100%.” This gets her distracted, “I always ask people who donate to Africa: Where’s your money going? [she pokes me with her finger, prodding] Do you know if it is still working? Did it really build something? [she pokes me again] Did it really help someone?” She throws up her hands, questioning. Then she shows me an app on her phone with constant updates on every single pump in every project and adds, “I know where my money is and what it’s doing. I can see it in real time!”. She never stops.

Source: https://www.water4mercy.org/projects

What Makes It Work

As I see it, there are three keys that make the whole project work and make it of interest to economists: stability, private ownership, and the use of decentralized knowledge.

The first two – stability and private ownership – are kind of related. The real insight is that people will only invest their time and energy into something if they expect to get the returns. Imagine a grocery store with a crowd of thugs waiting outside to rob every shopper exiting. Why go in and buy anything at all? It’ll just be stolen.

The same logic applies to investing in a water pump if corrupt local officials just come and take the water. Similarly, there’s little incentive to invest in a business, especially a physical one that can be physically plundered, when someone regularly robs the business owner. The robber can be a “proper” robber, or a mafia, or a gang, or a government or just some (un)officials from the government. The point is that, without some measure of stability and security, people don’t invest in those things.

Private property rights play a similar role. If you don’t own the land you farm, you can’t be sure that you and your family will reap the benefits over time from the farming. In this case, the people who take the fruits of your labor don’t have to be corrupt. You didn’t own them anyway.

It was important then that Nermine saw the local people had a long history of owning their land, homes and farmlands. This meant that property rights were clear and well established. That can be built upon with confidence that farm yields and business returns will go to the owners. That in turn provides an incentive to work hard, invest, and grow.

Those interested in this topic should read Hernando de Soto’s (2000) The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else. De Soto writes about problems in Peru and other countries. He makes clear the link between local governments - regulations -, property rights, and investment in business. In many parts of the world, when your business grows “too big” or “visibly big”, local government officials (corrupt and not) come in to get their cut. As a result, people underinvest in capital and also allocate a lot of time and resources to hiding capital when they do invest in it. It’s a very readable book and non-technical. I highly recommend it.

Decentralized knowledge is, in my mind, the last key. There are many ways to phrase this. Essentially, one big problem for developing economies is when well-intentioned foreign people come in and try to tell the locals what they should be doing. Because Nermine is a private person who saw the problems firsthand, and wanted something fundamental like providing a means for people to earn their own way and their own dignity, she helped provide a foundation upon which the local people can and do develop in the ways they best see fit. They grow the crops they want. They grow what they know grows well in their land. They form businesses to meet needs they know about. That’s all local decentralized knowledge, and it can’t truly be obtained from surveys, data, and governmental or NGO committees trying to decide what’s best. It can only truly come from the local people themselves. And, Nermine listened.

All these things mean that the water pours into fertile economic ground as well. The stability and property rights mean that local businesses flourish along with the local people. And, the economic growth provides the means to sustain the capital, equipment, water wells, and private businesses.

Of course, last but certainly not least, it takes a leader and a stubborn, talented, wonderful person like Nermine, to pull it all together, raise the funds, and see it through to completion.

Conclusion

Economics is amazing to me. It’s fascinating. There are only a few things that need to be in place and then life and prosperity flow forth, like water (sorry…I couldn’t resist). Some stability, reasonable rule of law and property rights, and humans flourish in a sustainable way.

How does it work? Why? Why in some places and not in others? Are there common laws for this? Can we help? Can we hurt? These are the questions that hook economists.

It's easy to write and complain about monetary policy, inflation, debt, and so on. But I want this column to also bring good news and hope too. And, I’m an economist. I’m proud to share the insights and beauty that economics does have to offer.

I’ll continue to discuss topics of the day, criticize and bemoan the bad state of economic affairs around the world. But let’s never forget that there are also good things happening in the world. There are silver linings around dark clouds. There are always reasons to smile.

Nermine is one private person. She saw a need. She pulled Catholic, Italian, Israeli, and American groups together to help local Africans pursue their own dreams and ambitions. She finally helped them earn their own dignity and be proud of their homes, heritage and families.

Reach out to her organization if you want to learn more, https://www.water4mercy.org/home-old.

As always, thank you for reading.

[1] Some of you might recognize Les’s name. I actually met Nermine through Les. He founded www.mainstreeteconomics.org to teach the average American about basic economics and to raise alarms about America’s economic challenges. His hope is for people to “Learn Economics and Vote Smart”, which I wholeheartedly support. I periodically reference Les’s articles and works, hence the potential familiarity of his name for some readers. Today, however, is about Nermine and her project.