What Are the Central Banks Doing?

What on earth are central banks doing? Honestly, some days I don’t think I have a clue anymore.

Photo by Pablo García Saldaña on Unsplash

Particles, Waves and “the Dual Nature of Inflation”

In physics, as I understand, there are two theories concerning the nature of light. One says light behaves like a particle. The other, that it behaves like a wave.

The analogy isn’t perfect, but there are sort of two dominant theories[1] in economics concerning the nature of inflation. One says it’s determined by the growth rate of the money supply (all else constant). The other says it’s controlled by interest rates[2].

In the same way that it might strike us as funny that physicists, after all these years, “still don’t understand something as ‘basic’ as light”, we might find it equally funny that economists “still don’t understand something as ‘basic’ as inflation”. I won’t push the analogy much further, but you get the idea. There’s a long-standing debate and both views seem to make a lot of sense at different times. They both fit different models of the economy. And, untangling which theory is right has been elusive.

Theories of Inflation and Empirical Tests

Many of us in the macroeconomics profession hoped that, at least, this current bout of inflation, and policies to fight inflation would help shed light on which of these theories might be wrong (data can only disprove, never prove, a theory). And, modern monetary policy is built on the interest-rate theory, so it looked like the one being challenged.

One among many reasons the interest-rate theory is dominant today is that the money-supply theory stopped making sense of the data somewhere in the late 1980s/early 1990s, and may never have worked at all. Today it is considered “old school”, and, at least in the United States, the Fed today claims not to use the money supply to influence inflation. Most monetary theorists agree, most monetary models claim this too, and most central bankers will say this[3].

Just to keep in the back of your mind, if the quantity of money theory were right, then for this latest wave of inflation we should have seen money supply growing rapidly well in advance of inflation. That is, money should have increased a lot. Then, 6-18 months later, inflation should have followed. Then, to fight the inflation, the Fed should have reduced the growth rate of the money supply and, 6-18 months later, inflation should have started to fall. The Fed is adamant that this is not how it works.

Instead, they will argue, interest rates control inflation. Central banks can target inflation, and then use an interest rate rule, called the “Taylor Rule”, named after John Taylor of Stanford University who first uncovered such rules in the early 1990s. Nearly all textbooks and all models used by the central banks themselves will explain that, in order for the interest rate rules to work, the central bank must raise or lower interest rates faster than inflation rises or falls.

This is because they are actually trying to control the real interest rate. The real interest you earn or pay on something is the nominal interest minus inflation. If you take a car loan out and pay 10% interest, but inflation is rising at 4%, then the “real interest” you pay is only 10 – 4, or 6%.

Higher real interest rates make us consume and invest less today, leading to less demand which leads to lower prices and inflation. Lower real interest rates encourage consumption and investment, leading to more demand which leads to higher prices and inflation. Remember,

real = nominal – inflation[4].

Having to move the nominal interest rate more than inflation is called “Taylor determinacy”, kand an example or two might help you see why it is thought to be important.

Imagine a world where the nominal interest rate is 2% and inflation is 2%. The real interest rate is then 0%, r = 2 -2 = 0.

Now imagine that inflation rises suddenly to 4%. Until the central bank does something, the real interest rate (r = 2 – 4% = -2%) has fallen to -2%. This fall in the real interest rate stimulates consumption and investment, demand starts rising and inflation will rise further if nothing is done.

Even if the central bank raises interest rates but does so by less than inflation rose, then interest rates will still be negative. That will continue to stimulate demand and inflation will rise even more.

Here’s an example: Suppose that when inflation rose by 2% policy makers only raised interest rates 1% so the real rate is -1% (r = 3 - 4 = -1%). That’s still lower than it was initially and still stimulates demand. Inflation will thus rise further, say, to 5 or 6%, and the real interest rate will be more negative, r = 3 – 6% = -3%. This further stimulates the economy. Inflation eventually spirals out of control.

Taylor determinacy: For interest rates to control inflation, the central bank must change them more than one-for-one with changes in inflation. Doing that moves the real interest rate which is what economists believe actually moves demand and hence prices.

Consider a central bank that follows Taylor determinacy. We start with interest rates at 2% and inflation at 2% so the real = 2 - 2 = 0%. Inflation rises to 4% like before. Initially r = 2 - 4 = -2%, like before. But this time the central bank raises interest rates by more than inflation, say, to 5%. The real interest rate turns positive ( r = 5 - 4 = +1%), higher than it was initially, and this discourages consumption and investment, dampening demand and slowing inflation. As inflation falls, the central bank lowers interest rates too until both settle at 2% again and real rates are zero.

This is the explicit mechanism and description in every textbook today. You hear Fed Chair Jay Powell explain this from the podium over and over at every Fed press conference. You hear the same in Europe and England and at every major central bank[5].

You’d expect, then, that more than a year into this crazy bout of inflation, we’d have interest rates rising faster – and being higher than – inflation so real rates would rise and dampen demand. But, you’d be wrong.

Here’s What Our Central Banks Have Done and Where They Are Today

The USA has one of the best cases.

Nominal interest rates are 5.25%,

inflation is 5%, and

the real interest rate = interest rates (5.25%) – inflation (5%) = +0.25%

That’s finally positive territory. But, keep in mind, just a few months ago inflation was higher than 5% and interest rates weren’t yet 5.25%. So, until now, interest rates were still negative!

Fine you say, but they are positive now. They finally caught up.

Okay, but by what mechanism did inflation fall? It wasn’t because they raised rates higher than inflation. That’s only happened now yet inflation fell from 9% in the summer of 2022 to 5% today. Why? How?

The Fed says it’s because they raised interest rates and that fought inflation. But they didn’t raise them early or fast enough for the mechanism they claim works to have worked. They actually did what I explained in my first example when interest rates didn’t rise enough and inflation spiraled out of control. But that’s not what happened. Inflation didn’t spiral out of control. It fell from 9% to 5%.

In the UK

nominal interest rates are 4.5%,

inflation is 8.7%, and

the real interest rate = interest rates (4.5%) – inflation (8.7%) = - 4.2%

Real interest rates are still seriously negative in England! What? After more than a year of high inflation in a country that’s been a leader of “inflation targeting”, uses an interest rate rule and follows Taylor determinacy, this doesn’t make sense.

In the EU

nominal interest rates are 3.75%,

inflation is 6.1%, and

the real interest rate = interest rates (3.75%) – inflation (6.1%) = - 2.35%.

Also negative in the EU!

What on earth is going on? Every one of these central banks preaches one thing from the podium, and does something else in reality.

Everyone knows about the Taylor rule. Finance people in banks and investment houses know about the Taylor rule. The US Fed even has an app on their Atlanta Fed website where you can use the Fed’s own real-time, actual data and compute the actual interest rate versus what the Fed’s own Taylor rule says it should be.

If you want to see it for yourself – with the Fed’s own explanation of the parameters based on their own estimates and past Fed chairwoman Janet Yellen’s public statements!!!! – here: https://www.atlantafed.org/cqer/research/taylor-rule (scroll down, click on the chart that says “chart”, and then scroll down past the explanation to find the chart you want to see).

The one online goes back to the 1980s, shows multiple versions of the Taylor rule with different parameters, and can be confusing, so here I cleaned up the graph a little and only use one of the Taylor rules they present.

The blue line is the Taylor rule and the purple line is the actual Fed interest rate (“Fed Funds Rate”). You can see at the end that they are way below the Taylor rule’s recommendation. The rule says interest rates should have hit 8% last year (blue line) but we still had them at zero (purple line). Only in 2022 did we noticeably move them (purple line). Then, indeed, we started raising them rapidly.

Now, in fairness, in 2022, they have been raising the Fed Funds Rate (“the” interest rate) faster than inflation’s been rising. But, for all of 2021 they didn’t. That should have led to even higher inflation in 2022. It didn’t.

The point is this: None of the central banks are practicing what they preach or following what their own models say they should do. And, inflation is not behaving like it’s being primarily controlled by interest rate policy.

Some of you may notice that the Fed also didn’t follow the Taylor rule in that earlier 2002-2006 period either. John Taylor himself and many others warned at the time that deviating from it would cause a financial problem, and many believe, in hindsight, that it was a big part of the cause of the 2008 financial crash. I don’t want to get into that here, and I’m not saying that we are setting up for another financial crash today. I’m just saying that no one is doing what they claim to be doing and what they know they should be doing according to their own models.

I can’t easily generate a Taylor rule for the UK and EU without more hours of work and searching online, but trust me, I had my students calculate it in class this Spring. It looks the same for the UK and EU as well. My students also did it for Australia, Japan, Canada and other countries. Almost no central bank is following it today.

They Don’t Follow Their Own Models and Advice, So….

They’ve brow beat us with “the quantity of money doesn’t matter” for the last 30 years. Surely they aren’t cutting the quantity of money…

Well, I’ll be…

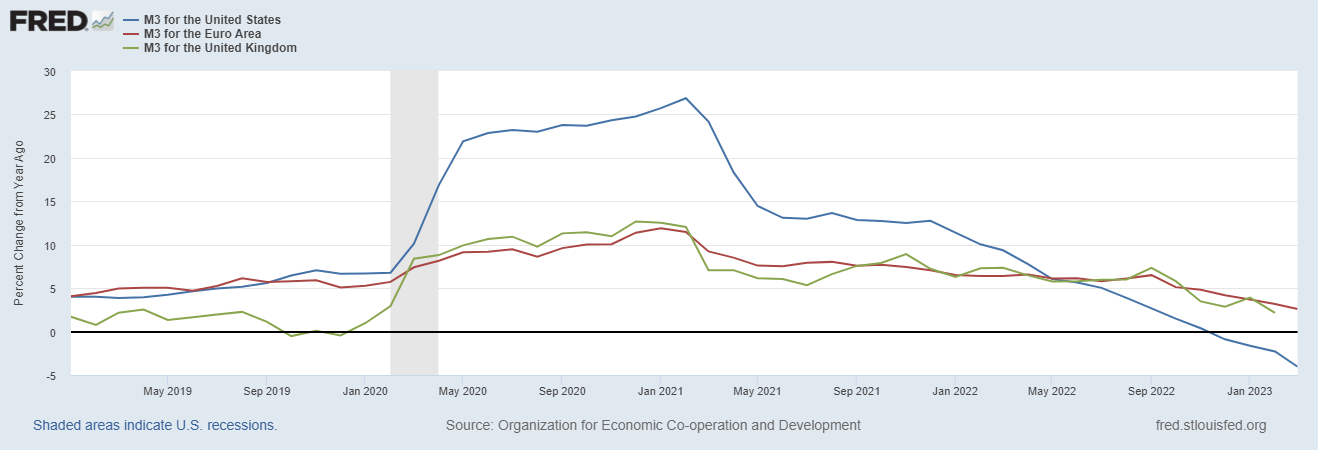

This graph shows the growth rate of the money supply in these countries. Normally it’s around 3-7%. Historically, really high growth would be 10%. The 1970s even hit all-time highs of 14% (all time highs from 1950 until 2020, that is). The US (blue line) topped 25%.

The green line is for the UK and red for the EU. All of them had a bump up in money growth in 2020, but more importantly, kept their feet on the accelerator in 2021 (way past what was justified for Covid in early 2020). All had subsequent inflation.

Which country started to get inflation more under control starting last summer, say, July 2022? And which country cut the money supply growth the most? Hmmm. Looks like the US with the blue line.

Now, if you ask any of these central bank chairs or their staff, they’ll tell you this is just them “unwinding the balance sheet”. They are not intentionally lowering the money supply. If you ask them, “well wouldn’t that also reduce the money supply?”, they’ll answer “yes”.

Everything and the Kitchen Sink

The first rule in medicine and monetary policy is “do no harm”.

Everything works with a long and varied lag. Now, the Fed finally got real interest rates into positive territory and have not only low, but actually negative money growth. This is throwing everything and the kitchen sink at inflation.

They could have slowed money growth more than a year ago. There was never justification for 25% money growth in the United States, in my opinion, in the first place. But even then, they could have slowed it in 2021 a lot. But they claim it is irrelevant for inflation, so no one cared.

Instead, they could have started raising interest rates rapidly and sooner, following their own models. But they didn’t.

Now they are doing both.

As a citizen living through this like everyone else, inflation is painful, and higher interest rates are painful. I’m also worried about a real bullwhip sort of effect with a much bigger recession coming than we need. Not that we’re seeing it yet. But it worries me.

As an economist, I’m frustrated because this still won’t allow us to distinguish between the two theories of inflation. The pro-interest rate camp will point to the final months when interest rates rose faster than inflation and say “ah ha! See it worked!”. The pro-money camp will point to the final months when the money supply finally turned negative and say “ah ha! See it still works!”.

This summer one thing I’m doing is gathering data with my friend and co-author, Jack French, to look at inflation episodes around the world back to 1970. Our goal will be to find only disproving examples. We will search for cases that clearly cut against one of the theories. We aren’t trying to support any of them. We are exploring as many contrary cases as we can, and then grouping them together to see what they tell us.

I’ll share some of those preliminary findings as we play with the data in the coming months. In the meantime, let’s watch the Fed’s, ECB’s, and other banks’ meetings in the coming weeks, and see what happens.

Oh… and watch for financial commentators to start noticing the massive dips in money growth rates. It’s going to continue to be an interesting monetary year.

[1] There is actually a third one today which says that it’s controlled by the expected present value of future government budgets. I’m personally very interested in this theory. In some way it is a unifying theory that makes sense of the other two as well. But we’ll set it aside for now. It’s also nearly impossible to test empirically.

[2] Controlling inflation and determining or causing inflation are not quite the same thing. There is a subtle difference that we’ll ignore for now.

[3] Here’s the ECB’s site explaining policy tools (no mention of money supply anymore): https://www.ecb.europa.eu/mopo/decisions/html/index.en.html

[4] Technically there are two slights of hand, or simplifications, if you like here. First, the “real interest rate” here is what I might call the short-run real interest rate or the financial real interest rate. The long-run real interest rate in an economy is pinned down by the marginal product of capital and hence less able to be manipulated by monetary policy. Second, interest rates include expected inflation, not current inflation. This second point would affect some of my numbers here, but won’t affect my overall argument. If you disagree by the time you read to the bottom email me. I’m open and interested.

[5] There is a theoretical critique that this is not how the models actually function. It’s based on Benhabib, Schmitt-Grohe and Uribe’s paper in 2002, “Monetary Policy and Multiple Equilibria”, American Economic Review 91 (1): 167-186. I’ll ignore this here. It’s too technical, but I think they are right. In any case, what I wrote above is indeed how it’s explained in books, in most papers, by most economists and by all policy makers.