Photo by Alexandra Gorn on Unsplash

If you listen to central bankers these days, you will hear them say they want to avoid the mistakes of the 1970s. They will also tell you that key lesson they learned from that period is not to start and stop policy, but instead to commit unwaveringly to low inflation. Sometimes commentators - and even the Fed Chair himself - will refer to this as the Paul Volker lesson, referring to the Fed Chair from 1979-1987, who is seen as the great slayer of inflation.

Let’s look at what happened in the 70s and why it’s a lesson for us, especially in 2023.

The 1960’s Phillips Curve

The Phillips Curve is the (normally negative) correlation of inflation and unemployment in an economy. These should generally be negatively related because, when aggregate demand increases, demand for all goods and services rises. This generates higher prices – inflation – and the need for businesses to hire more people which lowers unemployment. So, unemployment often falls when inflation rises and vice versa.

Please remember, as I warned in “It's baaack! The Phillips Curve Conversation”, that the Phillips Curve is a statistical correlation. It is not causal. That means, there is no sense in which unemployment itself rising or falling causes inflation to rise or fall, nor is there any sense in which raising inflation will itself cause unemployment to move. That causal inference is a mistaken application of the Phillips Curve.

Phillips discovered and published the UK curve first in 1958. Economists then looked for and found the negative correlation in nearly every country. Here’s what the US data looked like in the 1960s.

The 1960s Phillips Curve had a profound effect on the thinking of academics, policy makers and politicians alike. Because it was consistently found everywhere, it started to be treated as an economic law. The thinking was that, once you found it for a country, it was very stable and reliable. The next step was to use it for policy making. That’s when the problems started.

Policy makers and politicians began treating the Phillips Curve as a “menu of options”. Basically, they felt they could pick any point on the curve and “set the economy” there. That was very convenient.

And it felt very democratic. Politicians only needed to understand the “will of the people” concerning their appetite for inflation versus unemployment and set policy to match. Don’t like inflation? No problem, we can get it down to 1% but you have to suffer 7% unemployment. Oh, 7% is too high? No problem, let’s meet in the middle. How do you feel about 6% unemployment and maybe 1.5% inflation? And so on.

This thinking was dominant at the time.

The Breakdown of the Phillips Curve

In 1967, Milton Friedman[1] gave his Presidential Address to the American Economic Association (our biggest global gathering of academic economists). Without any empirical evidence at all, Friedman warned that if you try to pick a point on the Phillips Curve and keep the economy there, the curve will move. In particular, if you try to pick high inflation and low unemployment, when the curve moves, you’ll end up with both high inflation and high unemployment. And that’s what happened next.

Signs of trouble could already be seen in the data. It’s clear that from 1966 to 1968, inflation was rising as unemployment was stable, or even slightly declining. According to the bad Phillips-Curve-as-a-menu logic, policy makers targeted too low an unemployment rate on the Phillips Curve and the economy was overheating.

By the end of 1969, inflation had reached almost 6% and unemployment had reached 3.5%. Labor markets were seen as too tight and this was fueling inflation.

The Fed aimed for a higher unemployment rate in order to lower inflation. They cut the money supply and raised interest rates. The US economy entered a recession. This lowered inflation and raised unemployment, moving up along the Phillips Curve, like they planned. So, it seemed to work!

The green line is the money supply which they started cutting seriously in April 1969. That cut in the money supply raised the Fed’s policy rate[2], the federal funds rate (black line). Monetary policy works through “long and variable lags” and, sure enough, 6-18 months later we can see that unemployment started rising and inflation started falling from its peak.

The next thing that happened is what central bankers fear today.

The Mistake Central Bankers Fear Today

Feeling that the economy was moving to the right point on the Phillips Curve, the Fed seems to have assumed inflation would just drop to where “it’s supposed to be” on the Phillips Curve with 5% unemployment. Given that, they needed to focus on preventing a recession.

Therefore, in 1971 they pivoted, to use a term circulating today, and began increasing the money supply and cutting interest rates.

GRAPH: 1970 to 1973

It must have felt like a success. They moved the economy out of the recession and to a “better” point on the Phillips Curve with a little higher unemployment and lower inflation. I’m sure they felt like they got the mix right and that Milton Friedman was wrong.

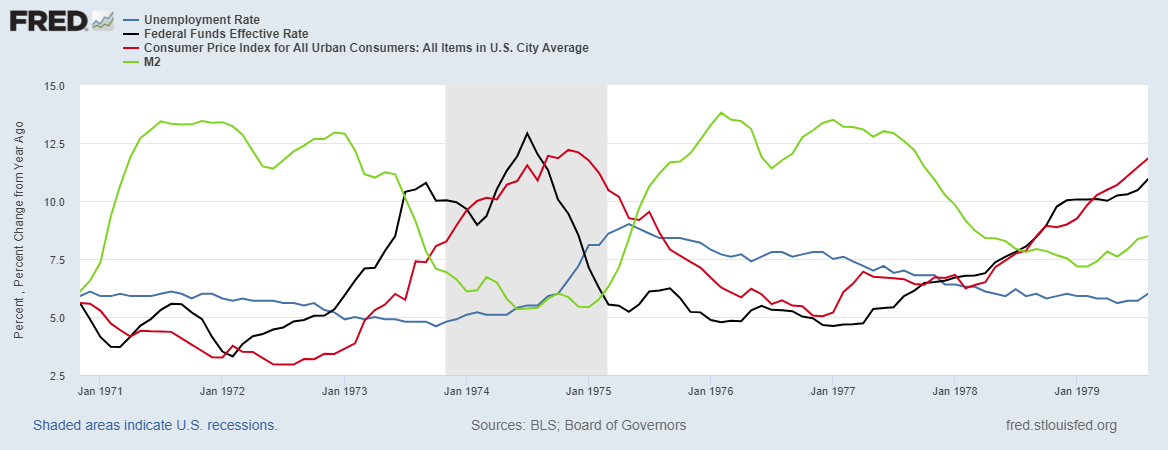

GRAPH: 1970 to 1975

From January 1973, however, inflation started to rise again. Unemployment seemed stable but inflation was again getting out of control. The Fed knew what to do.

They began cutting the money supply and raising interest rates over the January to June 1973 period. But inflation kept rising.

Then in June/July 1973 they began cutting the money supply in earnest and raising rates. Inflation kept rising and we entered a recession.

But, according to bad Phillips Curve logic, by late 1974 (near the end of the graph) unemployment finally started to rise which caused inflation to start falling as well. That was the sign that we were moving back to the right spot on the Phillips Curve and could focus on fighting the recession again! Time to pivot once again. And they did.

GRAPH: 1970 to 1977

The Fed began pumping money into the economy and lowering interest rates to fight the recession. From summer 1974 interest rates were falling and the money supply was rising a little. Then, from January 1975, the Fed pushed the monetary gas pedal to the floor again and kept pumping money into the economy at about a 12% annual growth rate. Again, it must have felt like a success: we exited the recession and unemployment and inflation both fell.

But this already contradicted the Phillips Curve logic. The bad logic says that unemployment falling should raise inflation, not lower it. Clearly Friedman was right that the curve wasn’t as stable as people had thought. It’s funny that he also won the Nobel Prize in Economics the following year, in 1976, mostly for his work on monetary theory that showed “significant inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon”, meaning “the result of printing money”.

The Phillips Curves – plural - looked a little different in the 1970s than they did in the 1960s. The Phillips “relationship” was moving, as Friedman predicted.

The above graph represents two or three Phillips Curves, one in that 1970-72 period (blue), then the red triangles show it shifting way out to the right from 1973 to 1975. The orange squares show yet another Phillips Curve for the 1976-78 period.

Why The Curve Shifts

Sure, like we’d expect, there are some Phillips Curve relationships between inflation and unemployment in short horizons, but once policy makers try to pick a spot and target it, the curve moves. The reason is that people come to expect the new inflation rate and this turns out to make the whole thing collapse.

Once everyone expects, say 10% inflation, they build it into contracts. Prices and wages all rise at the same rate and unemployment can settle towards its natural rate for the economy, independent of whether inflation is high or low. In short: everything adjusts to the inflation rate and then fundamentals determine employment.

That shift Friedman warned about in 1967 can be seen in the graph by the different blue, orange and red Phillips Curves. The move from blue to red was a period of both rising inflation and rising unemployment. We later started calling such scenarios “stagflation”.

The Final Straw: Why Central Bankers Don’t Sleep at Night

By 1977, inflation was starting to rise again, unemployment was falling and money was still growing at around 12% annually. The US ended 1977 with 6.7% inflation and 6.4% unemployment. There was every reason to believe that the Fed could keep tightening and get inflation back under control. Sure, it’s on a new Phillips Curve, but it worked before. Yes, it drives a recession, but it works. Or so they thought.

Interest rates started 1977 in January around 5-6% but hit 10% by January 1979. And despite cutting the money growth rate and raising interest rates, inflation persisted.

Inflation hit 9.25% in January 1979. High interest rates surely threatened to cause another recession and you can see the Fed’s policy makers started to lose their nerve. In the first half of 1979 – at the end of the graph below - they slowed the rise of interest rates (flattened black line) and printed a little more money (green line).

GRAPH: 1970 to 1979

A Quick Recap of the 1970s Yo-Yo Monetary Policy

1969 – Fight Inflation: less money, higher interest rates

6-18 months later: Economy enters recession

1971 (Pivot) – Stimulate Economy: more money, lower interest rates

6-18 months later: Inflation rises

1973 (Pivot again) – Fight Inflation: less money, higher interest rates

6-18 months later: Economy enters recession

1974 & 1975 (Pivot again) – Stimulate Economy: more money, lower interest rates

6-18 months later: Inflation rises

1977 (Pivot again) – Fight Inflation: less money, higher interest rates

6-18 months later: Inflation rises AND Economy enters recession

The Age of Volker: The Great Hope of Central Bankers Today

Paul Volker took over as Chair of the Federal Reserve on August 6, 1979. He took the lessons of Friedman and the evidence of the 1970s to heart and committed to reducing inflation. He was a large, Texan, standing 6 feet 7 inches (2.01 meters) and earning him the nickname of “Tall Paul”. He was a large, dominant figure in every regard. Paul Volker brought credibility back to the US Fed.

Part of the problem of inflation was that, by the end of the 1970s, the Fed had lost its credibility as an inflation fighter. It would reduce inflation but, whenever that led to a recession, the Fed would then pivot and flood the economy with cheap money, once again leading to more inflation. People came to understand and expect this. In modern lingo, we’d say that “inflation expectations” had become unanchored by the end of the 70s, something central bankers are trying to avoid today.

The Volker Fed began raising interest rates and insisted on maintaining them until inflation was gone, no matter the pain and no matter how long it would take.

GRAPH: 1979 to 1987

Volker remained in office until August 1987. He raised interest rates at the beginning of the 1980s. They peaked at 19.10% in June 1981. Inflation had already peaked at 14.6% in March 1980, two years earlier!

Inflation fell slowly but persistently throughout the 1980s, landing at only 3.9% by the time he left office and unemployment was only 6% (the end of the above graph).

In Friedman’s terms, the Phillips Curve fell down and to the left as inflation expectations settled down and the Fed regained credibility. By the end of the 1990s, inflation was only 2.9% and unemployment was around 4%, the same as it was in 2019, just before Covid.

Key Lessons

The key lessons for policy are:

(1) The Phillips Curve is a short-run phenomenon, a statistical correlation, not a causal relationship. If you try to exploit it, treating it as causal, it will move on you[3].

(2) Pivoting too soon and too often generates a yo-yo effect in the economy, is what loses a central bank’s credibility and hence leads to the un-anchoring of expectations.

(3) Once inflation expectations become unanchored, inflation takes off and is very hard to get back under control. That’s seen by looking at the mid-1970s to the early 1980s. Central bankers were doing everything they could to get inflation back down, but until everyone believed they would stick with it, it wouldn’t fall.

These are the lessons every central bank chair and every central bank policy committee knows deep in their bones. In real time, it always looks easy to pivot and then tighten if inflation really gets out of control again. That may work once, it may work twice, but eventually things spin out of control.

Every major central bank chair has recently stated that they are committed to getting inflation back to its 2% target, no matter how long it takes. We’ll see if they can do it.

If we enter a global recession in 2023, every central banker will be under tremendous pressure to ease the money supply again. Just a little. Just enough to alleviate the pain. This will test them. We’ll all see if they are more like Arthur Burns and William Miller (Fed chairs in the 1970s) or Paul Volker.

[1] There were other economists thinking similarly, Edmund Phelps, who won the Nobel Prize in 2006 in part for his work on this topic. One modification of the Phillips Curve is often called the Friedman-Phelps Phillips Curve in honor of them both. Friedman was the more famous of the two and won the Nobel Prize in 1976 for his lifetime work in macroeconomics, especially monetary policy.

[2] The interest rate is “the price of money”. When you decrease the supply of something, it becomes more scare and its price rises.

[3] I suspect this is a deeper issue. Policy can’t pick what it wants the economy to do. It might be able to guide, curtail and nudge, but it can’t just pick specific outcomes. When it tries, the effort itself causes its own failure.

Hi Chris, so you expect that fighting the inflation will take longer time to reach stable condition?