Why We are So Unhappy Today

Photo by Stormseeker on Unsplash

The economy’s great. Unemployment is low. Inflation has finally fallen. Why on Earth are we all so unhappy?

Economically speaking, I think the answer is clear. Our salaries didn’t rise as fast as inflation did, and so many of us are actually poorer today than we were a few years ago. At best, we’re like the mouse in his wheel, running full speed for the last four years, just to stay still. And, that leaves us tired, frustrated, and feeling like we are sinking.

Understanding the Implications of Inflation

Inflation slowed but prices will not be returning to their pre-Covid levels. People seem to know this intellectually, but don’t really feel it in their bones. Why do I say that? Because I continue to hear people say “yes, inflation fell, but we still aren’t done getting prices back down”. I hear it from friends. I hear it on the financial news from people who should know better.

The price level is best thought of as the average of all the prices in our economy. When the price level is rising, we call that inflation. Inflation rose and fell, but the price level just rose.

Unless inflation turns negative, so that the price level is actually falling, prices will not return to their pre-Covid levels. Yet, for some reason, everyone seems to have in their minds that when inflation goes away, we’ll be back to where we were before inflation hit.

I think that’s because our experience, at least in the United States, for the last forty years or so has been of a low inflation economy. Gas prices might rise in the summer, but then fall back down. Home heating prices rise, then fall back down. TV’s, laptops, etc. have just gotten cheaper over time. But those are all relative price movements, and inflation is about “all prices” rising. Price level changes happen for different reasons than relative price changes, and price level changes have different effects as well.

Here’s a graph of inflation and the price level in the United States during the 1970s-1980s when we had our last big battle with inflation. The blue line is the price level. The red, dashed line is inflation.

The blue line rises everywhere – with only a mild blip or two – and yet inflation rose rapidly in the mid-1970s, hit 12% (right-side axis for percentages), then fell, only to rise again until it peaked at 14% in 1980.

Inflation fell dramatically after 1980, settling around 4-5% for the rest of the 1980s. That’s about where inflation was at the beginning of the graph, in 1973. So… INFLATION fell back down to its 1973 level but the PRICE LEVEL never returned to its 1973 level. We know this. We can all see it. We can all understand it. But somehow we don’t feel it intuitively, leaving people disillusioned with the recent great fight against inflation… “but prices still didn’t fall”.

No. They won’t. Prices will not return to their pre-Covid levels.

Relative Price Confusion and Old-School Inflation Thinking

“But, some prices did fall”, people tell me all the time. They have in mind some prices that spiked during the pandemic. You can always find prices that went up, and some that fell back down.

That’s why it’s important to look at the price level (i.e., “all prices”). If some prices rise and others fall, exactly offsetting the effects of the rising prices, then the price level will not move. The average of +1 and -1 is zero, as is the average of +2 and -2 or +100 and -100. The extreme cases don’t tell us anything about the average rise.

For the price level to rise persistently over a long time, it must have been the case that all prices, on average, rose. And, if some prices spiked up and then fell – which definitely happened – then a rising price level over that whole time – which also happened – tells me that the spikes up were bigger than the drops down and/or, on average, there were more increases than decreases.

Inflation can feel very confusing to us, especially when it first takes off. Some prices move a lot, others don’t. It’s very hard for us as observers of this in real time to tell if movements are just relative price movements or price level movements. It takes time for data analysts to discern this too. It take months and sometimes quarters to collect, calculate and average all those prices, and for the trend to finally emerge.

In the meantime, the wording of news reports can add to the confusion. There’s “car price inflation” but “gas price deflation” and “chicken price inflation” but some other goods saw “deflation”. That’s all very confusing. And, it’s technically right if inflation just means the rise in any price. But, macroeconomists generally reserve the term inflation for the percentage change in the price level only. All others would be “car prices rose and gas prices fell” and so on. I think that’s more clear.

Additionally, macroeconomists traditionally distinguished between an increase in the price level and an increase in inflation. The difference was that inflation was thought of as something that was on-going, while a change in the price level was a one-off thing.

We don’t hear this distinction as often today, and I think that also causes some confusion[1]. It matters, because one-time shocks to the economy can raise or lower the price level once. But to get a sustained increase, i.e., inflation, you need shocks that are repeated or continuing. That means the causes of price level changes are different than causes of inflation.

Examples of one-time, temporary shocks that hit and then go away are sudden supply chain problems, wars, Covid lockdowns, and chip shortages. If those are widespread enough, affecting enough of the economy at once, they generate a rise then fall in the price level.

One-time permanent shocks that hit and stay are things like changes in tariffs or other taxes, big government spending packages, a one-time increase in the money supply, and so on. These cause the price level to rise once, and then remain higher thereafter.

A permanent increase in the price level can certainly feel like inflation initially, because it can take a few years for the price level to rise all the way to its new level. But, left unattended, the process will stop. The price level will settle.

Those are all “increases in the price level”, by which we mean one-time increases in the price level.

To get inflation – a continual and sustained increase in the price level – you need something that pushes (a) “all” prices and (b) continues. Continuous shocks of this type are things like an increase in the rate of money growth, a persistent and/or growing government budget deficit, and a persistent loss of faith in the government issuing the currency. This last one is why bankrupt governments are often unable to stop inflation as it just spirals out of control. Once faith in the government is gone, no one wants to hold that government’s currency, and inflation rises ever faster as people try to dump it.

The distinction between price level changes and inflation matters because the tools to stop it are different. That’s why, when prices first started rising in the United States, the Fed argued it was transitory. Quite logically, the Fed thought the Covid shock and supply-chain shock and so on was a one-time event that would lead to some prices spiking (used cars, computer chips… toilet paper… remember that?), but would go away. And, if it went away, prices would return to their old levels. That would not have been inflation, and the Fed would not have needed to intervene.

But, sustained inflation or rising prices over a long period of time requires something else to be changed. It requires a slower rate of money growth or an improving government budget situation or both. Almost nothing else will do it. And, since the Fed controls the money, they have the mandate to control inflation over time.

Milton Friedman’s famous quote that “inflation is everywhere and always a monetary phenomenon” captures this one-time versus permanent issue. And, actually the correct quote reflects this more clearly. He actually argued that “substantial inflation is everywhere and always a monetary phenomenon[2]” [my italics added].

Price level changes can happen for a million reasons. But, to get that substantial and persistent inflation, you need monetary policy. Why not fiscal policy? Well, in extreme cases, as mentioned before, you do see inflation turn into hyperinflation when governments collapse. But, when they start running out of other people’s money, they nearly always print more. And that’s monetary policy. Bad fiscal policies nearly always devolve into bad monetary policy, hence Friedman’s saying.

Today, many people – myself included – think about fiscal and monetary policy together as “government policies”, and I’d state Friedman’s note more like “substantial inflation is everywhere and always a government phenomenon”. There is no way for a functioning economy to have substantial and sustained inflation without the government causing it.

Real Wages and Feeling the Burn of Inflation

To bring it all back together, let’s look at inflation. In theory, consistent and reasonable inflation is no problem. If we have 2% inflation or 5% inflation that is consistent, then everyone adjusts. Suppose it’s 5%, just to pick a number. My salary will rise by 5% a year. Since I’ll have 5% more money when everything I already buy costs 5% more, then I’m no better or worse off.

If my boss wants to give me a raise, they give me 6% one year, 5% for “cost of living adjustment” and 1% as a “real raise”. I can now by 1% more than I could the year before.

The problem is when inflation is not consistent. If my boss and I both think inflation will be 5% and I get a 6% raise but inflation turns out to be 2%, then they accidentally gave me a 4% real raise! If my boss did that with most workers – or even kept everyone else at 5% - then my boss’s real costs just went up a lot. They might even have to lay off some people.

When inflation is relatively low, however, at 2% or so, and fluctuates year to year from 1.5% to 2.5%, then a boss who wants to just offset inflation will offer 2% a year in base pay. Some years I will be a little better off (when inflation turns out to be only 1.5%) and some years worse off (when it’s 2.5%), but it’ll wash out on my side and on my boss’s side.

And here’s the rub…

Because Americans have lived with low inflation for so long, essentially since the 1980s, we collectively continued to expect about 2% a year despite inflation actually rising to about 9%. This meant that most people who stayed in their jobs mostly lost real purchasing power.

Consider a hypothetical company going through Covid. In 2020, the company wasn’t sure it would survive Covid, have funds to pay for building modifications and other changes (plexiglass, outdoor seating, Zoom cameras in university classrooms, testing facilities, and so on). Everyone worried about their jobs gladly accepted a flat salary in 2020. Many places even cut salaries a little during the first three months of Covid when business was zero. Many executive teams took public pay cuts, for example.

Now consider a good employee who stayed at that company. The employer in this scenario would have cut salaries by 10% for three months in 2020, then held them constant the next year (2021) and finally, perhaps, raised them by 2% in 2022, thinking inflation would normalize. This would be an accurate description of the scenario for all professors I know, many friends in other industries and so on.

Over those three years, those employees saw zero net salary increases. A 10% cut for 3 months is a 2% annual cut and is completely offset by the 2% raise later. But, prices in the United States rose by about 20% over that same three-year period. That employee lost 20% of their real salary!

That person would logically be very bitter today. I can imagine them feeling that they stuck it out during Covid, maybe volunteered at work to help with testing, worked odd hours, suddenly figured out how to switch everything to online, and so on. And what did they get? A 20% real paycut! They see higher prices in every restaurant, at the grocery store, when buying their kids’ back-to-school clothes, and everywhere else in life.

And, when they hear on TV (okay to not be old fashioned… on X, FB, or a podcast…) that “the U.S. economy is in great shape! And inflation has fallen! And unemployment is low with a strong labor market!” They feel screwed and a bit bitter with the world.

This is one example. It’s very typical of the people I talk too. I suspect it’s typical of a lot of people’s experience.

When we look at the aggregate data, it looks a little better because it includes low-paying wage jobs that saw a better increase post-pandemic when people couldn’t find fast-food workers, line cooks and the like. A national average also includes the high-end earners who always seem to land on their feet.

The average of all wages in the United States did rise some, but not as much as inflation.

The aggregate numbers look like this

2020: wages rose by 5% and inflation was 1% so, on average, people saw a 4% real wage gain

2021: wages rose by 5% and inflation was 7% so, on average, people saw a 2% decline in real wages

2022: wages rose by 4% and inflation was 6% so, on average, people saw a 2% decline in real wages

2023: wages rose by 4% and inflation was 3% so, on average, people saw a 1% gain again.

Since a lot of people saw 2020 was an anomaly, I’m not sure they felt the wage gain that year as much as in a normal year. The following two years in a row, they lost real wages on average. By late 2023, wages were rising and inflation was finally slow enough that people were breaking even. But, by this time, I think people were looking around at prices and realizing, “wow, everything’s a lot more expensive”. That is, they were feeling and seeing the bite of lower real wages.

I think this is a very big reason that people are so down on the economy and feel upset these days. Yeah, inflation is down, and, yeah, I have kept my job through all this, but my salary is flat and prices are much higher, and now I have Zoom meetings in addition to the regular work I used to do pre-Covid. It’s generally an unpleasant place to be.

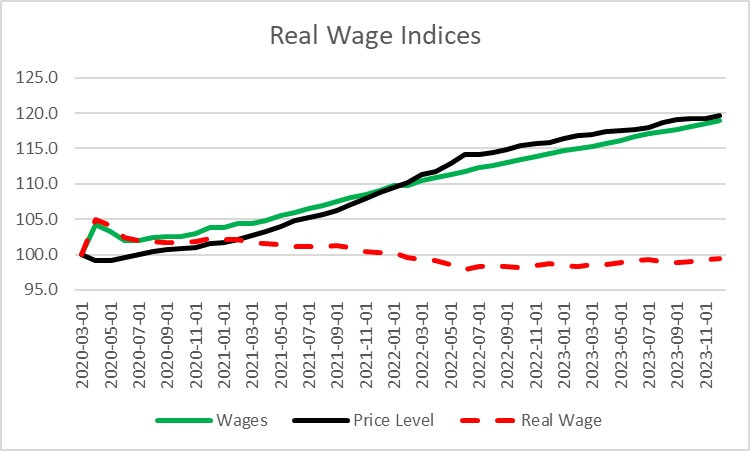

The Real Wage Story in Two Pictures to Conclude

This first graph looks at average wages (green line), the price level (black line) and real wages. To make it all comparable, I set everything to 100 at the beginning of Covid (March 2020). As long as we compare things to the beginning (the 100), we can easily see the change.

Source: FRED Database. Nominal Wages and CPI. My calculation for the real wage.

At the beginning, the price level (black) dropped a little during Covid and wages (green) spiked up. I’m not 100% sure why wages spiked by about 5% unless the number includes Covid stimulus payments, although it shouldn’t include that. In any case, it means real wages (red) also rose by a little more than 5% since wages spiked and prices fell. The real purchasing power of wages went way up. Ironically, that’s also when people weren’t going outside and spending. GDP dropped by about 10% at that same time in the United States. Not a happy time.

From that point onward, wages (green) rose consistently, but the price level (black) raced right past. All along, real wages (red) were flat or negative, shown by falling below 100 in the graph.

Remember, this is an average of all wages for the whole economy. It’s just one measure, but I think a good indicator of what most of us experienced: flat to negative real wage growth over the last four years.

I tried in this next graph to make each year jump out more. The graph isn’t perfect, but hopefully it makes sense.

Here I reset everything back to 100 at the beginning of every year[3]. Otherwise, it’s the same data.

Source: FRED Database. Nominal Wages and CPI. My calculation for the real wage.

Once again, each year starts by being reset to 100 so we can see the change over each year a little better. What we see is that in year 1 (2020), nominal wages (green) rose and stayed above 100 – near 103 – the whole year while the price level (black) was generally below 100, near 99. As a result, real wages (red) rose a lot, hitting 105 initially during that initial Covid period of March to May, 2020.

In 2021, everything was set to 100 at the beginning of the year, then diverged from there. Prices (black) were rising faster and faster over that whole year, ending at 107 in that year alone. That’s a 7% increase for the year. Wages (green) also rose but not nearly as much, peaking at 105. Real wages stayed down around 99. That’s below the 100 where they started, so real wages fell over the year by 1%.

In 2022, the trend is even more pronounced. The black line being above the green line reflects the pain of losing purchasing power and that divergence was the worst in 2022. The red line (real wages) fell below that 99, or even 98, level for most of the year.

2023 saw the green and black lines growing together most of the year with green pulling out ahead in parts. That’s where wages were finally catching up as inflation slowed. Real wages in red were finally back in that normal 101 range by year’s end.

By looking at the “black line higher than green line equaling financial pain”,

2020 shows the least pain, but that was the year of Covid, lockdowns, elections, riots. Not a happy time. No one will remember that year in a positive light.

2021 was painful financially (black > green). We were otherwise poking our heads out of our homes, wearing masks to work, getting shots, and struggling to understand how to move forward.

2022 was the most painful financially (black >> green) and we were otherwise trying to return to normal. But I think we all were really feeling the pain in 2022. After two years of serious inflation for the first time in 40 years, even though we were removing masks and trying to return to normal, it was hard, prices were higher, we delayed car purchases, house purchases, and saw interest rates rising.

2023 was finally returning to financial normalcy (green = black or green < black in 2023. Yeah, life looked normal, but the price tags were high, interest rates were even higher, and we still needed to delay big purchases. So… the “new pain” (i.e., green vs. black) wasn’t adding to our hurt, but we were still hung over from being financially hit so hard in 2021 and 2022.

Honestly, I think this is a huge factor behind why we all feel so glum. Statistically, things look better, but we aren’t statistics, we’re people. And life is hard.

Let’s hope, for everyone’s sake, it will only continue to improve from here.

[1] For those more academic readers, I think one reason for this is because our research is largely done with DSGE models around zero-inflation steady states. Modern monetary economists often think of zero-inflation steady state, deviations from it and then returning to it. We almost never think about changes to steady state inflation itself. That means “inflation” is always “just” capturing temporary movements in the price level.

[2] See page 193 of Friedman’s Book, “Money Mischief: Episodes in Monetary History” in Chapter Eight just before the section on “The Proximate Cause of Inflation”. I tried to find a weblink for readers who don’t own libraries of econ books :-) and found this article by Sumner who makes the point but I’ll keep looking. Anyway here’s the Sumner link: https://www.econlib.org/persistent-inflation-is-always-and-everywhere-a-monetary-phenomenon/

[3] To be clear, for those who are number people, at the beginning of every year I take the current wage divided by the current wage times 100. Then I hold the denominator at that number all year and just update the numerator each month. That makes an index. I do that for each variable. Then restart that process January the next year. Now, each year starts at 100.