3% Inflation: Who, What, When, Where, and Why

The latest US inflation numbers came out Wednesday (July 12, 2023) and show inflation down to 3%. Hurrah!

Last week I got several emails and questions about inflation: is it real? why? will it last? what’s next? and so on. I thought I’d take the chance to share my thoughts with everyone in case you have the same questions. Hope this sheds some light.

Good news: the CPI shows 3% inflation in June!

The latest US Consumer Price Index (link here[1]) shows headline inflation in June this year was finally at 3%. This is great news after 9% inflation exactly one year ago (June 2022) . We all screamed at 9%, and should breathe a sigh of relieved at 3%.

Yes, our target is 2%, but anything in the 1-3% range would be acceptable to most people in normal times. There’s still some work to do to get us consistently down to 2% and keep it there, but 3% is on that path from 9% to 2% and that’s good. Personally, I think they’ll have a harder time preventing it from going below 2%, but more on that another time although you’ll see below why I have that possibility in mind.

Less good news: the FED’s preferred measure for CPI shows 4.8% inflation in June.

When looking at the trend in inflation to determine if it’s real, temporary, rising or falling over time, the FED prefers to look at inflation numbers excluding food and energy prices, because food and energy prices are very volatile as we’ll see in a few graphs below.

The FED says its truly preferred measure of inflation is the Personal Consumption Expenditures Excluding Food and Energy (PCE) but it won’t be updated until July 28th. It was last measured at 4.6% in May. But the CPI numbers just released also have versions excluding food and energy which the FED takes a little more seriously (for understanding deep trends) than the headline number. Unfortunately, that CPI excluding food and energy was still at 4.8% in June.

Here they both are over the last 5 years.

You can see they both rose. Headline CPI (not in graph) hit 9%, while these peaked around 5-7%. They didn’t rise as high, and are not falling as low as headline CPI.

The red line – “CPI less food and energy”– runs longer on the graph because it was just updated, while the blue line, PCE, is the one that only comes out next week. Nevertheless, you can see that PCE has been flat and not falling. That’s a problem if the FED is right, and it’s the best metric for “the true inflation trend” in the economy.

In normal times, you can see July 2018 – Jan 2019, they are pretty close to one another. You can also see from the beginning of the graph that the FED normally tries to keep them around 2%.

In the following graph, you can see why the FED likes to exclude food and energy. The prices of both of those are very volatile. The graph shows headline CPI (green), CPI excluding food and energy (red), and PCE (blue) going back to 1950. The takeaway is just that headline CPI (green line), which includes energy and food, is much more volatile than the others, hitting higher peaks and lower valleys as well.

Excluding food and inflation tells us more about the trend, or underlying inflation. But, that means the CPI without food and energy and PCE should give everyone cause to pause the enthusiasm over the 3% headline number. We shouldn’t get too excited by one or even two good months of headline CPI. The FED knows this and will be cautious and more guardedly optimistic, but optimistic nonetheless. I think that’s the right view.

Breaking the numbers down

The Bureau of Labor Statistics has some great interactive graphs that capture the latest report. For anyone interested, I encourage you to look at them online. I found it interesting, for example, that the biggest spikes were in Phoenix, Arizona. I didn’t know that. Anyway, here’s the link:

Below, I’ll just show you a couple of graphs that should be interesting to most readers.

First is the main chart. It alone tells us a lot about what’s driving the headline results.

Without saying too much, you can see that food (blue) and all other items (green) are still near 5%, but the fall in energy prices ( -16.7%) is what pulled the overall number (red) down. If you exclude energy, the blue and green numbers would put inflation around 5%, excluding blue too gives you just the green number which is the 4.8% number the FED prefers to look at.

All items vs food

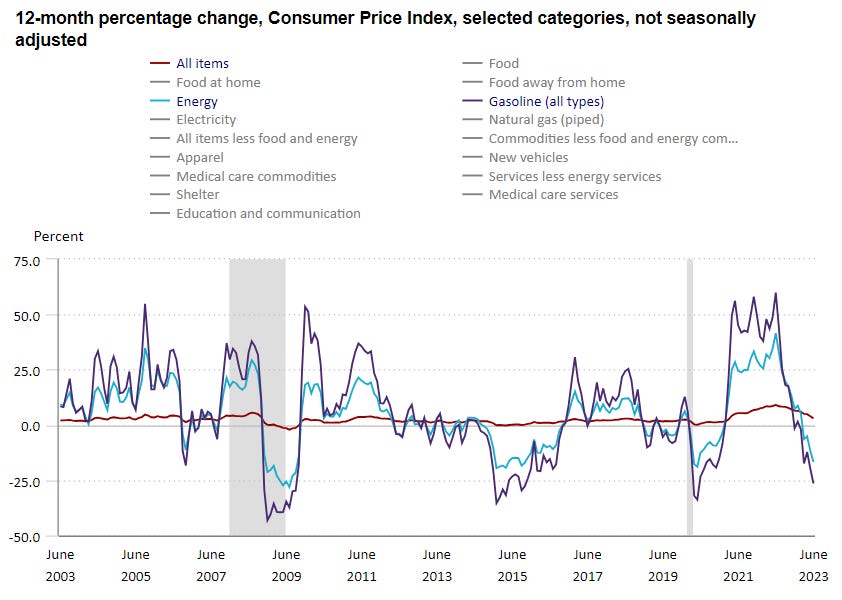

The next graphs give the time series data for each item in the CPI calculation. These give us a slightly deeper sense of what sector’s prices are driving inflation. We’ll mostly look at the end of the graph on the right side after the thin grey bar marking the Covid recession.

The red line is headline CPI (“All items”). The dark blue line is “Food at home”. There was a big spike in the blue line during Covid in 2020. It then dropped in June 2021 (to 0.7%) only to peak again at 13.5% the following August in 2022. All the while, “Food away from home” (green line) was climbing, slowly at first, then ever more until it plateaued at the end. It didn’t drop at the end like the “Food at home” (dark blue) did. Maybe it’s ticking down. Maybe not. We need to watch this number for another month or so.

Higher prices in any given sector[2] come from less supply or more demand or both. My read for the green and dark blue lines is this. The blue line (home food) spiked during Covid as demand for eating at home spiked. There were also some supply restrictions due to food industries trying to convert on the fly from focusing on restaurant to home markets.

The (blue) drop in June 2021 was likely people sick of eating at home and venturing back out to restaurants. It was the first post-Covid summer. The subsequent spike, which was huge, I don’t know. That peaked in June 2022 when inflation also peaked at 9%. So I think it was an inflation phenomenon, not just local supply and demand.

The green line (food away from home) is more interesting to me. While also following the inflation trend, my microeconomic story here would be that it rose during Covid because the supply of restaurant services declined. You might also recall higher prices for drive-through, having them deliver to your car, eating in parking lots outfitted with tables, etc. Those were higher costs of doing business combined with staffing shortages, supply issues and less competition as other restaurants stayed closed. As we exited Covid, demand returned but some closed restaurants never re-opened and staff shortages have persisted. The situation seems to be a bit better today, but staffing is still tight if you talk with folks in the restaurant world. If I’m right, prices here will not drop as fast since they are more due to fundamental issues than to inflation.

Volatile energy

The next chart just shows us, once again, how volatile energy prices are and why they are generally ignored for the purpose of predicting true, underlying inflation versus merely temporary price swings.

First, notice the magnitude. The volatility is self-evident as are how much more extreme are the highs and lows. The red line is the same red line (headline CPI inflation) as the one in the above graphs. Gas and energy jump all over the place with gas repeatedly breaking 50% levels.

Of potentially more interest is that the energy price spike for the USA was not due to the war in Ukraine. The war in Ukraine broke out in February 2022. That was – potentially – captured here in the final spike in the blue and purple lines’ plateau at the end, just before they start dropping dramatically. But even that is a stretch in my opinion. That final plateau with three spikes (November 2021 at 58.1%, May 2021 at 56.2% and June 2022 at 59.9%) appears totally independent of the war breaking out in February 2022, at least to me.

What got us here?

The FED’s answer (I think) would be: The FED under-appreciated the inflation challenge in Spring and Summer of 2021. They then raised interests more rapidly than they have in many years and this is finally feeding through the system, conquering inflation.

The purple line is the FED policy rate (a.k.a., “the interest rate”). The strongest evidence is that, as it finally rises dramatically, headline inflation finally starts to fall dramatically too. Visually, I’m looking at the increase in the purple line between Jan 2022 and Jul 2022 when the green line also peaks and starts declining.

Notice, however, that looking at interest rates hikes (purple) and the FED’s preferred measure, PCE (in blue), the evidence of success is zero. It peaked in Jan 2022, but hasn’t really fallen. That’s a problem for the FED.

The traditional monetarist answer: The FED under-appreciated the inflation challenge in Spring and Summer of 2021. When they finally slowed the growth rate of money, after a lag, it led to lower inflation. Visually, take that big purple lump (money supply growth) and imagine sliding it rightward in the graph by 12 months. That’s when inflation rose. It’s end, then, would also correspond to when inflation slowed. And mentally sliding it is the “lag effect” of 12 months. This is back-of-the-envelope, but seems largely right.

The first thing that probably jumps out is the magnitude. See my earlier columns for discussions of the magnitude, but historically the highest we ever increased the money supply was 13-14% in the 1970s. Here it went way over 20% and we kept it there, peaking around January 2021, a year after the Covid recession. Anyway… I’ve discussed that at length elsewhere (see links in footnote[4]).

Rather than dig into details, I will add here that the two most shocking things to me are (1) the magnitude of the spike, again, waaaay out of historical bounds, and, (2) the actual negative growth rate of money. Historically it has never turned negative, at least back to January 1961 at the start of the FED’s data for money. Here’s the graph.

I am not sure why people aren’t talking more about this. It’s never been negative before. They are actually decreasing the amount of money in the economy, not just slowing it’s rate of growth. Traditional theory suggests this will lead to deflation (actually falling prices) in about 12 months. Modern theory says it’s less clear. But, remember QE, “quantitative easing”? This is literally the opposite. Whatever effect the FED believed QE had, this will have the opposite.

Pick your monetary explanation

I’ve complained about this in the past, but you can use the data to support both the money and the interest rate stories. Traditionally, the two were linked. More money meant lower interest rates. Less money meant higher interest rates. So, they should totally coincide with one another. Hence, the period of crazy high money growth should also correspond to the period of crazy low interest rates. And, it does.

The problem – at least for me – is that that the FED, and much modern monetary theory say the two are now unrelated. The FED explicitly claims that, since it started paying interest on reserves in 2014, the two are completely unrelated[5]. I think that view is too extreme and flawed. Part of my academic research agenda is understanding just why and how.

The fiscal situation

The other prominent theory is the Fiscal Theory of the Price Level (FTPL) ,and it’s really hard to check, since it depends on how people believe the government will handle budgets in the future. When they believe future government budgets will be more in deficit, they lose a little faith in the dollar – seen as sort of “shares in the government” – and that loss of faith leads to a loss in value of each dollar, which is inflation. But we don’t have good data on people’s true beliefs.

Nevertheless, the government’s spending also pumped money into the economy. Covid spending package #1 in Q2 2020 was a near 50% increase in government spending over Q2 2019. And then one year later, we did package #2 in Q1 of 2021 was another 50% increase over Q1 2020 (just before package #1).

In any case, that dramatic increase in spending and resulting deficits was also a likely cause of the subsequent inflation. The fact that the FED financed much of it – that is, bought the debt directly, essentially “monetarizing it all” – is part of why the massive money supply growth and massive fiscal spending boom are linked here. That is often the case in war times and other extreme periods, and those periods are almost always inflationary.

What next?

Well, inflation is down. I expect it will continue to fall no matter how you measure it. We’ll keep interest rates high for at least a year[6]. If we also keep money growth negative, then inflation should continue to fall for at least another year. We’ll essentially be draining the economy of the massive flood of money we poured into it for all of 2020 and 2021.

The question is what effect all of this will have on the real economy. That is, will it cause a recession and an increase in unemployment or not?

Honestly, I don’t know. A year ago, I would have said “yes”, because that large a reduction in the money supply, and that rapid an increase in interest rates should reduce aggregate spending, slow the economy, and lead to higher unemployment. I still expect some sort of slowdown but it hasn’t yet materialized. That is a mystery in and of itself.

In the end, let me say this: 3% inflation is good. We should appreciate it. Nevertheless, we shouldn’t read too much into the numbers of any one month. But, it looks good and looks like things are moving in the right direction. Since we know there’s a lag, the increase in interest rates last year and this year, combined with a slowing and now decreasing supply of money, should have effects through this the end of this year and into the next.

Barring any other big shocks, I believe inflation will come down. Actually, in 2024/2025, I think our discussion will be about getting inflation up to our 2% target. I also think a (possibly mild) recession is more likely than not just on logical grounds.

Those are my thoughts and expectations as of today.

Next week on Tuesday and Wednesday (July 25 & 26), the FED’s policy committee meets. Most people are expecting that the 4.8% CPI (less energy and food) will convince the committee to raise interest rates another quarter point just to convince us all that they are committed to getting inflation back down. Let’s see how they see things and how they explain them. The press conference will be informative in this regard. I’ll be watching.

Thank you so much for reading.

[1] BLS Consumer Price Index Summary: https://www.bls.gov/news.release/cpi.nr0.htm

[2] For those of you curious, I qualify this with “in any given sector” because a rise in all prices comes from bad monetary policy. In technical jargon, I’m talking here about microeconomics and relative prices.

[3] I use M3 here instead of the traditional M2. M3 is broader and less preferred. But, the FED changed how we calculate M2 in May 2020 so I don’t want that change to affect our results here. And, if you plot them together M2 and M3 nearly overlay perfectly. See this link for a graph of them together: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=173zg .

[4] “Who’s Afraid of the 1970’s” (February 2023) probably captures all of this the best. https://globalecon.substack.com/p/whos-afraid-of-the-1970s and the other, earlier one is “Who’s To Blame for Inflation”( March 2022), https://globalecon.substack.com/p/whos-to-blame-for-inflation .

[5] See the FED’s own publication: “The Fed’s “Ample-Reserves” Approach to Implementing Monetary Policy” (February 2020). https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/feds/files/2020022pap.pdf

[6] I can’t help but note that high interest rates do not lower inflation. It’s the rate of change, not the level of interest rates, that has the effect. Persistently high interest rates are associated with high, not low, inflation.