Alright, I’m tired of hearing this discussion in the financial media[1]. I feel compelled to write this comment.

About a month ago longer-term interest rates on U.S. Treasuries (i.e., “U.S. government bonds”) suddenly rose a lot and a lot faster than people were expecting. Financial commentators on nearly every show I listen to and in every paper I read began discussing whether the bond market was doing the Fed’s job “for it”, by which they mean: are the higher interest rates going to push inflation down so that the Fed doesn’t have to raise rates again to push inflation down itself.

The whole issue revolves around the financial market participants’ obsession with wanting to believe that interest rates will fall soon and return to a world of nearly-free liquidity.

I have several issues with this. The first is that the period of near-free liquidity was the anomaly. Near zero (and sometimes negative) interest rates are not normal, and they are a sign of government intervention artificially overstimulating the economy to keep it on life support. It’s a serious problem to be in that state of the world for very long. But, I’m not focusing on that today.

Instead, I’ll focus on the second, more technical, set of issues I have with this discussion. First, I’ll explain that this is always how policy is supposed to work. Higher bond rates should always be “doing the Fed’s job”. Second, I’ll explain why the idea that rates on government bonds rising rapidly independent of the will of the Fed would actually be a bad sign, not a good one. It would signal higher, not lower inflation to come.

Issue 1: Fed Rate-Hikes Should Raise Other Interest Rates

Fed rate hikes should raise other interest rates. That is exactly how a modern central bank always does its job. Therefore, when the Fed hikes interest rates up or pulls them down, bond rates should follow, always be doing the bidding of the Fed. It’s meaningless to say bond rates are “doing the Fed’s job, so the Fed doesn’t have to”.

The correct way to say it is that market participants hope that long term rates are finally rising in response to Fed rate-hikes over the last year or so. We were wondering if Fed rate-hikes were raising other rates sufficiently, and thereby sufficiently having an anti-inflationary effect. Finally we see higher Fed rates bleeding into several markets, and that’s a sign that the high-rate medicine is working, slowing the economy, and therefore (hopefully) inflation as well.

The essential logic of how all this works is that the Fed determines the foundational, or base, interest rate in the economy. Technically, for the modern Fed, this is the interest paid to banks on the reserves (IOR[2]) they hold at the Fed. The Fed pays IOR - currently 5.4% - directly to the banks. Think of it like the interest banks earn on their “checking accounts” at the Fed. Banks then use these “bank funds” (called “federal funds”) to borrow and lend to each other so they can manage day-to-day liquidity challenges. The market in which that happens is called the federal funds market and it determines the “federal funds rate” (FFR)[3].

You can see that, if you were a bank, and you could park money effortlessly and without limit at the Fed at IOR, you’d only lend to other banks if you could earn more. So FFR is bigger than IOR. But, trading with other banks is usually extremely short term, often just overnight to meet unusually higher demands by a bank’s customers on a single day, so the return is better than IOR, but still small. Indeed, FFR is 5.5% and IOR is 5.4%.

If banks want even more money, they could lend longer term to other banks or large funds that manage money for corporations, and so on. But, they would need to have even higher returns to do that. Then you get to other loans banks make for cars, houses, and so on. Those all need to be higher still to compensate the bank for risk and other costs. [Note: the more the risk, the higher the interest rate has to be.]

It's like this picture of rocks where the Fed directly manipulates the bottom rock and all other interest rates sit on top of that, held upright by market forces.

Photo by Photoholgic on Unsplash

We can even imagine that the rocks should all be the same size in a perfect world. Now even some rocks being wider and flatter than others can reflect that sometimes markets don’t pass those stacking rates on perfectly and rates can get squished rather than rise like they should.

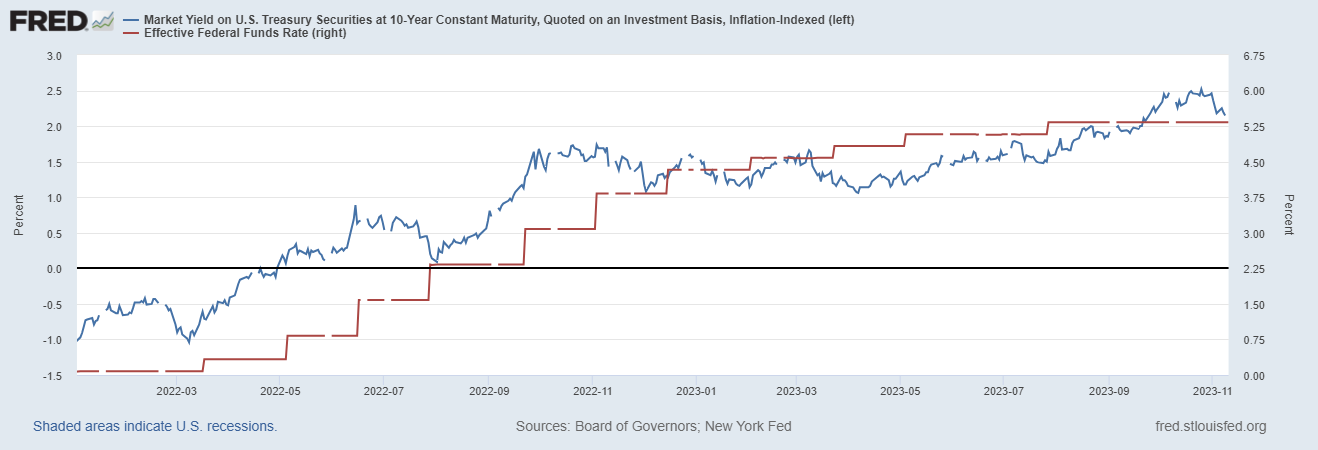

The excitement over bonds “doing the Fed’s job” is all about the end of this next graph where Fed rates (red) haven’t been rising, but then suddenly, in recent months, bond rates (blue) rose a lot.

Ignore the values of the axes[4]. What’s key is that, generally, you can see that when the Fed (red) raises rates[5], the long-term interest rate on bonds (blue) rises. But sometimes there’s a lag. Then, at the end, the Fed wasn’t raising rates, but bonds rates jumped.

The Fed raises interest rates to fight inflation. Market traders don’t want higher interest rates. They are therefore hoping that bond rates rising will dampen demand enough to slow inflation, and give the Fed reason not to raise rates further. This is the actual meaning of “bond rates doing the Fed’s job”.

But, that’s a silly way to phrase it. It’s just catchy, but actually meaningless on a basic level. Market rates should always “be doing the Fed’s job”. That’s how the system works. If the Fed raises IOR and no market rates changed, then it would have no effect on the economy. And, we know there are “long and variable lags” from when the Fed takes an action to the time when that action has a meaningful impact on the economy.

So things ought to be working exactly as they should, albeit with some lags. If not, then there’s actually bad trouble on the horizon.

Issue 2: Suddenly Rising Bond Rates Would Be A Negative and Inflationary Sign

Taken literally, “bond markets doing the Fed’s job” implies the two are disconnected. Market rates on longer-term US debt are rising independent of anything the Fed is doing. If true, it would be bad, not good. It might be true. It worries me. It’s not something to be giddy about.

Only two things lead to higher interest rates in the long run.

First, higher inflation, not lower inflation, is associated with higher interest rates. Nominal interest rates are the real rate plus expected future inflation (i = r + exp. inflation). If I’m going to lend money to a bank or the government (i.e., buy a bond) for the next year, then I need some return, “r”. But inflation also erodes the value of money over time so I need to consider what I think inflation will be, “exp. inflation”. Otherwise I could agree on a return, but inflation would wipe out the value of the money and I’d actually lose money. So, if I need a return of, say, 2% (i.e., r = 2%) and I expect inflation to be 3% (i.e., exp.inflation = 3%), then I charge you my 2% (“r”) plus 3% for inflation, or 5% altogether. All else equal,

if inflation is 5%, I’d charge you my 2% plus 5% = 7%

if inflation is 9%, I’d charge you my 2% plus 9% = 11%.

Therefore, all else equal, higher inflation for long periods of time is associated with higher interest rates, not lower ones. And… fair warning… policymakers holding interest rates high for long periods of time will also cause/necessitate higher inflation or a collapse in real returns (the “r”).

When people initially noticed that long-term rates weren’t rising as fast as inflation over the last 2 years, it was actually a sign most people believed to indicate that inflation wouldn’t remain at 9%, but would drop. Again, if I lend to you for several years and expect inflation to be high in only one year, I raise the interest rate I charge by a little, but not a lot because inflation is expected to return to normal. It’s only if I believe inflation remain high that I need to really raise the rate I charge.

The discussion of the “yield curve inversion” was exactly this: short-term interest rates were higher than long-term rates (the opposite should be true in normal times) and this phenomenon is called an “inversion”. But that was clearly a good, not a bad sign. It was telling us that market participants believed inflation would come back down.

Today, long-term rates are rising. This is hopefully due to some delayed effects of higher Fed policy rates (i.e., the stack of rocks story plus some delay). If it’s not, the first problem is that it suggests higher, not lower, future inflation. If inflation starts rising more, the Fed will have to raise rates more in the coming months, not lower them. That is the opposite of what the talking heads in the financial sector are hoping for.

The second thing that could raise interest rates is that the “r” part of the interest rate equation could rise. This could happen for very deep, fundamental and good reasons. Namely, it could happen because the return to capital investments in the United States is rising. But usually this sort of increase – called an increase in the marginal product of capital – is tiny. It wouldn’t usually drive rates to rise that much and certainly not that fast. And, not surprisingly, it’s not at all what anyone thinks is driving the bond rate increases.

The other thing that could raise “r”, which is the return investors need in order to lend money to the government (i.e., buy government bonds), is higher risk. The more risky an investment, the higher return I need to lend and compensate me for the risk of doing so.

We discussed in my last post on “War, Debt and Inflation”[6] that the U.S. government is in bad financial shape, and the situation is only projected to get worse. And, the sign that investors are worried about the government’s financial stability is that interest rates on government debt start rising rapidly. Rapidly rising government bond rates precede all fiscal-monetary crises.

I do not think this is fully the case today! But… I do worry that it is a part of the reason rates are suddenly rising. I hope it is not, and I’m not predicting an economic collapse today. It is a warning, though.

When investors (lenders) worry about the bond issuers’ (borrowers’) credit worthiness, demand for the bonds drops at current rates as investors back off, requiring higher returns to compensate them and get them back into the market.

That would happen independently of the Fed, and based on bad financial projections for the government. That would be made worse if others in the market were also demanding less U.S. government bonds, as is the case today with both Japan and China buying less, and other countries following suit to some degree.

When/if we hit a crisis period, you’ll know. We’ll all know. Interest rates will spike and we’ll hear on the news that buyers aren’t showing up in bond markets to buy U.S. government bonds. We are not there yet, but I worry we are slowly inching ever closer.

What happens in that case?

Well, essentially one of two things generally are likely to happen. Either, investors stop buying, the creditworthiness of the government is seriously called into question, and everyone flees that country’s currency (leading to truly high inflation[7]). Or, the Fed buys up the slack that no one else wants to buy. That is called “monetizing the debt” and also leads to truly high inflation.

This means that the scenarios where the “bond markets are doing the Fed’s job” today are all bad. They all imply much higher inflation, and potentially imply a major financial collapse in the case where things spin way out of control.

Conclusion

Hopefully that explains why it bugs me to no end to hear financial commentators gleefully hoping the bond market is doing the Fed’s job. They are happy, because they think it means inflation will fall, and the Fed won’t need to raise rates when actually it means very much the opposite.

Let’s hope that what’s happening is that higher Fed policy rates (IOR, FFR, etc.) are finally feeding through the financial system and raising all interest rates as they should. That would mean a general financial tightening, and, hopefully, dampening of demand that leads to less inflation.

That would be good and get commentators to the result they want: less inflation, therefore, less reason for more Fed hikes, and an eventual normalization of interest rates and inflation.

To my mind, normal would be 2% average inflation and 3-4% interest rates.

[1] There are many examples. Here’s one example on Bloomberg: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-11-09/-dark-matter-bond-metric-mesmerizes-wall-street-and-washington?cmpid=BBD111323_NEF&utm_medium=email&utm_source=newsletter&utm_term=231113&utm_campaign=nef

[2] For “Interest On Reserves”, IOR.

[3] For many years the Fed was setting the FFR directly in the federal funds market. So we still talk about Fed policy in this way as if they set the FFR even though they don’t do that today.

[4] Note, I ask you to ignore the values on the axes because I couldn’t find free and public bond rates to use. I used FRED data instead but all the long-term bond rates in the FRED data base are adjusted rates, holding risk constant and such. As a result, the the rate they report is only about 2%. Today’s (11/13/2023) 10 year bond rate is around 4.6%, and, indeed, it should be over 5.5% which is the FFR. This is a “squished, flattened” rock in the stack for sure, but that’s not the controversy right now.

[5] There was an excellent and interesting discussion at the Private Enterprise Research Center at my PhD alma mater, Texas A&M University, for a while: https://perc.tamu.edu/Blog . They were discussing if this was working in reverse: market rates were rising, forcing the Fed to raise rates as well. Now, that was an interesting thought! And, it’s a surprisingly hard one to resolve. Scroll back to 2022 to see those blogs. It’s an excellent site, by the way.

[6] https://globalecon.substack.com/p/war-inflation-and-debt

[7] We are talking about inflation like 20% or more in countries where this happens. It has to be enough inflation to devalue the outstanding present value of the debt, enough to rebalance the macroeconomy. For those interested, Google “fiscal dominance”, “financial crisis”, and/or “balance of payments crises”. Although remember, the U.S. doesn’t have a fixed exchange rate, so, luckily, we can’t have a balance of payments crisis, but the mechanism driving such a crisis is otherwise the same as what I’m describing.

Yeah. Funny I put this one out today of all days. That super soft CPI report told markets that the FED is done raising rates and long rates ... exactly... stepped in a hole. Will be curious to see how it plays out over the coming weeks.

Long rates stepped in a hole today.