Currency Trends and Team's Research

This is a short update for everyone that our Quinnipiac Global Econ Student Research Team continues to produce weekly reports. I don’t send them them all because I think you’d get overwhelmed. But, you can always find them here on our companion website: https://www.globaleconomics.net/

In reviewing the team’s reports this past week, I noticed that the exchange rates in the “Pacific” countries are moving almost opposite of the “Atlantic” countries. It inspired me to pause and see what’s going on around the world.

The Pacific Countries

Our team produces a weekly report on exchange rates for Australia (AUD), New Zealand (NZD), Japan (JPY) and South Korea (KRW) which we loosely call “Pacific countries”. The exchange rates are inverted so that an increase here means a stronger domestic currency. (Link: Global Econ Team Pacific Region Reports)

Here’s the graph for the last 3 months (middle line is average, dotted lines are +1 and -1 standard deviation, called the upper- and lower-bounds, respectively):

The common pattern here is that all of these rose in the April to May period. Three of them moved a lot: JPY (Japan), KRW (Korea) and NZD (New Zealand) all went from below their lower bounds to above their upper bounds, a more than a +2 standard deviation swing for this sample.

The Australian AUD did similarly but was largely within it’s upper and lower bound and showed more volatility at the beginning. I would guess that if you averaged that pre-April period, it’d be around the average whereas, averaging the period before the rise (somewhere mid/late March) for the other three would have likely been below the lower bound.

That’s all to say that the pattern is largely the same, just more pronounced for Japan, Korea and New Zealand. All the currencies strengthened significantly during this period but fell dramatically starting around May.

Since these are all relative to the US dollar, the simplest explanation is that something happened in the US. A logical thought is that market participants still expected US Fed rate cuts this year, until the April 30th / May 1st FOMC meeting when the Fed announced no rate cuts and that they expect to wait and see. US inflation data is still stronger than expected so they’ll keep interest rates higher. Markets likely saw this a sign that there will be fewer rate cuts this year, hence a slight weakening of the USD which made all the Pacific currencies relatively stronger.

If that’s the driver, however, then we should see the same for the Atlantic countries’ exchange rates, but we don’t…

Euro-Atlantic Countries

Here is the graph from the team report on exchange rates for Canada (CAD), the Euro Area (EUR), Switzerland (CHF) and the United Kingdom (GBP). (Link: Global Econ Team Euro-Atlantic Region Reports).

The pattern is largely the opposite of that seen in the Pacific region graphs. All the Atlantic currencies strengthen early in that March-April period, right when the Pacific countries’ currencies are weakening. They generally remain lowest (weakest) right when the Pacific rates are highest (strongest) and generally - except maybe Swiss, CHF - show a strengthening at the end, again, in the complete opposite pattern of the Pacific countries.

Both sets of graphs cannot be caused by the same US Fed’s policy announcement at the beginning of May. If the Fed’s announcement surprised world markets, it should surprise them all the same.

Inflation and Interest Rates

To think about it, I look at how these economies are all performing more broadly. I look at inflation, interest rates, GDP growth, and government debt and deficits. We start with inflation and interest rates1.

Most of the countries display inflation below 3%. Exceptions are Australia (3.6%), New Zealand (4%) and the USA (3.4%). Switzerland is the anomaly here with 1.4%, the only country we follow that has inflation below 2%.

As a result of the recent fight against inflation, most countries still have relatively high interest rates, generally in the 4-5.5% range. The US and New Zealand are at the top of that range with 5.5% rates and Switzerland is at the bottom with 1.5% which is not surprising given the very low Swiss inflation rate of 1.4%. The anomaly here is Japan. With 2.9% inflation, Japan only has a 0.1% interest rate. They are the only country (other than China that I know of and which I don’t write about here) that is actually trying to re-ignite inflation. I commented last year on Japan’s struggle to raise inflation (see The Japanese Economic Warning, May 2023).

In itself, this doesn’t explain the currency patterns we started with. But, it does seem that our sample of Pacific countries, on average, still have higher inflation that the Atlantic ones. Falling inflation rates with still relatively high interest rates in Europe could raise real returns and hence make the Atlantic-area currencies more valuable relative to the USD where inflation is still high despite high interest rates. That’s different than the case of the Pacific countries where inflation and interest rates are high, as they are in the USA. Of course that doesn’t explain the different pattern over the last few months, but I’m just looking for some obvious and common differences across the regions at this point.

GDP Growth

Higher GDP growth can be related to inflation in two different ways. Let’s call them the “good” and the “bad” ways.

The good way would be when productivity increases. That raises output which increases the supply of goods and services, lowering the prices for most of those goods and services. This lowers inflation.

The bad way would be when something causes demand for goods and services to rise. This also raises output as suppliers try to meet rising demand and raises the prices for most of those goods and services. This is very likely the story here, post-pandemic, where governments printed money and deficit-financed extra spending, raising demand dramatically. This raises inflation.

Both these cases would be increased GDP but for different reasons and hence with different inflation implications.

In the bad case, in addition to the demand stimulus, ones prices start to rise, Nominal GDP will increase further due to the inflation itself. Remember that a businesses’ sales (which collectively for all businesses in an economy add up to Nominal GDP) are the prices they sell at times how many things they sell. That is, revenue is price times quantity, P*Q. For the entire economy, the “Q” part is real GDP. That is, real goods and services. The “P” part is just the price. So, Nominal GDP = P*Q for the whole economy and can rise just due to the price part rising.

All my numbers here are only Nominal GDP growth number. We don’t know the true cause, but it’s widely believed that a lot of bad growth occurred in recent years due to over active government stimulus worldwide which led to inflation everywhere.

Euro-Atlantic growth is only 0.2%-0.9%, which is low. And that’s nominal growth, so subtract inflation and those numbers would all be negative, suggesting that real production is down. Unemployment is 6% or more in Canada and the Euro region and 4% in the UK. All this points to weak to negative real GDP growth in those countries.

The Pacific numbers are not uniform at all. Japan has -2% Nominal GDP growth (and 2.9% inflation) implying serious real GDP trouble. Australia and New Zealand have anemic to zero growth at 0% and 1.5%, respectively, while South Korea looks strong with 3.5% growth. South Korean inflation is also down to 2.9% and unemployment (not shown in graph) is only 2.8%, suggesting a very strong economy today indeed. This is better than the USA’s situation with 3.0% GDP growth but still 3.4% inflation and unemployment around 3.9% .

Out of curiosity I looked up real US GDP growth which is reported to be 1.6% (link to BEA here). That’s still positive and hence good, but it means that about half the Nominal GDP number is indeed just inflation. The question is whether the other half is organic and therefore meaningful or just driven by government spending.

Government Debt and Deficits

We can look at government deficit and debt to get an idea for our last question about growth being organic or not. A lot of debt suggests lots of GDP stimulus in the past and a government budget deficit suggests the possibility of government GDP stimulus now.

Debt and deficit numbers are released much less often so these numbers are generally from the end of 2023.

A pattern we might expect to see after the pandemic is one of high debt, reflecting lots of pandemic spending and stimulus, but low deficits or even surpluses today as the government moves past the pandemic and pays down its debts.

That is exactly the pattern we see in Switzerland where debt to GDP is around 38.3% (not high by most measures) and the government is actually running surplus of .5%. In 2020, Swiss debt to GDP was 43.2% when it also ran a deficit of -3.1%. 2021 saw the deficit drop to -0.3% and turn positive in 2022 to 1.2% then to 0.5% in 2023, the number we see presented here. Inflation peaked around 3.4% about 1.5-2 years after the pandemic (late 2022 to early 2023).

Australia did similarly, but with less debt overall. Currently (2023) Australia has a debt to GDP ratio of only 22.3%, down from 28.6% in 2021 and 24.8% in 2022. During those times, the deficit was -4.8% in 2020 when Covid hit, then worsened to -6.6% in 2021 and retreated to -1.4% by 2022. Inflation then peaked in Q4 2022 at 7.8%.

All the other countries seem to have much higher debt to GDP and are still running larger deficits, suggesting they are still inflating GDP by pumping government funds into the economy.

The USA and Canada have debt to GDP ratios above 100% at this point and both are still running deficits although Canada’s -1.3% seems less bad than the USA’s. At -6.3% of GDP, the US government’s deficit is way out of bounds for what is normal in a healthy economy.

Traditionally, anything worse than -3% in normal times is concerning. Exceeding -3% required an economic crisis. Here is the data back to 1948. I drew a a black line at 0% and a red line at -3%.

Source: Trading Trading Economics (link here)

The idea that the US would be between those -4% and -8% marks at any time other than pure crisis is very troubling. All else equal, this should suggest more US inflation and a weaker US dollar over the long term. No normal economist I can find, left, right or center, feel that a -6% deficit is warranted when GDP is growing at all, must less at 3%.

Relatively speaking, however, the Euro area and UK are in a similar situation. The UK’s graph goes back to 1948 as well and looks very similar (link for those interested). The Euro area’s graph only goes back to 1999 when they launched the Euro and is less clear since there is not a “Euro fiscal government” that runs it’s own deficit and accumulates it’s own debt burden. Rather, Euro debt and deficit numbers are averaged from member countries’ debts and deficits.

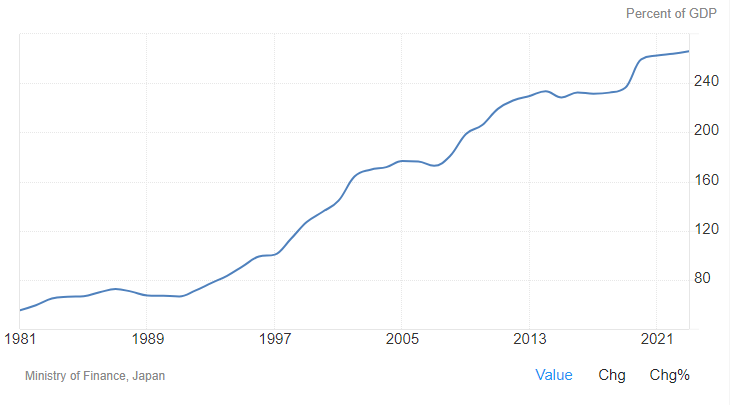

The real anomaly again is JAPAN with 264% debt to GDP and still running a -6% deficit! That’s completely insane. Here’s Japan’s debt to GDP back to 1980.

Japanese economic growth slowed around 1990 and never really recovered. (I think that’s due to long-term consequences of its industrial policy but I’ll comment on that elsewhere). Japanese policy makers seem to have decided to borrow their way back to health. 1990 to 2024 is how long? Let’s see… 34 years of this and still running -6% deficits? Maybe it’s not working. Just a thought.

The worry everyone has is that US policy makers want that here too! We copied much of their monetary policy, long termed in the literature “unconventional monetary policy” because it was so outside of what was considered normal. That’s where we all got quantitative easing, yield curve control, control of interest rates via interest on reserves and the strange effects on over-night inter-bank markets (the “federal funds market” in the US). Many of us are worried we’ll follow suit on deficit and debt policy too.

None of this Explains the Pattern

None of this really helps explain the Pacific versus Atlantic exchange rate patterns I started with. The US should have inflation and a weak dollar. Our GDP growth is oddly strong and very likely government driven which also should be concerning.

The only thing I see as notably different between the US relative to the Atlantic countries and relative to the Pacific ones is that GDP growth in Europe looks consistent but generally weak and positive while it’s inconsistent in the Pacific countries. Japan has -2% and South Korea has 3.5%.

Why that would matter is beyond me. Perhaps market traders think growth is slowly recovering in Europe or at least not dropping while in the Pacific area it’s less clear. Therefore recent US data that inflation persists but growth is slowing suggests the European economies will be stronger (hence stronger currencies on average) while Pacific ones are unclear or negative (hence weaker currencies).

But this isn’t new information. Why the big changes that essentially reverse at the beginning of May? I’m really not sure.

Long-Term Trends and Conclusions

The long-term trend should be a weaker US dollar and economy as we move toward a Japanese-style economy with strange monetary policy run by a central bank with a bloated balance sheet and a fiscal policy that believes there’s no end to how much it can borrow. Any countries, including the US and Japan, that move away from that trend toward more responsible monetary policy and more sound fiscal policies should see slowly stronger currencies.

How long is long term? No one knows. Usually it’s decades not months or even years.

In the meantime, something is different in the Euro-Atlantic region compared to the Pacific one. We’ll keep watching. My research team is doing a great job and I couldn’t be prouder of their work. And their results keep me thinking.

Many thanks to my team members. Check out their weekly reports and hopefully soon some monthly or quarterly reports (companion site link).

Thank you for reading.

And the basic linkages of interest are two: (1) central banks raise interest rates to fight inflation and (2), all else equal, if a country raises its interest rates, it calls global investment into the country, raising demand for the country’s currency, strengthening it.