I’ve been thinking about how to share parts of one of my research projects with you. This is a first effort.

This work is being done jointly with Jack French and Daniel Hogan. We are using data from the MacroHistory Database (reference at end and link to data in this footnote1) which contains a range of data on 18 countries from 1870 to 2020. Our aim is to have a first draft of a paper on inflation and inflation theories by Christmas.

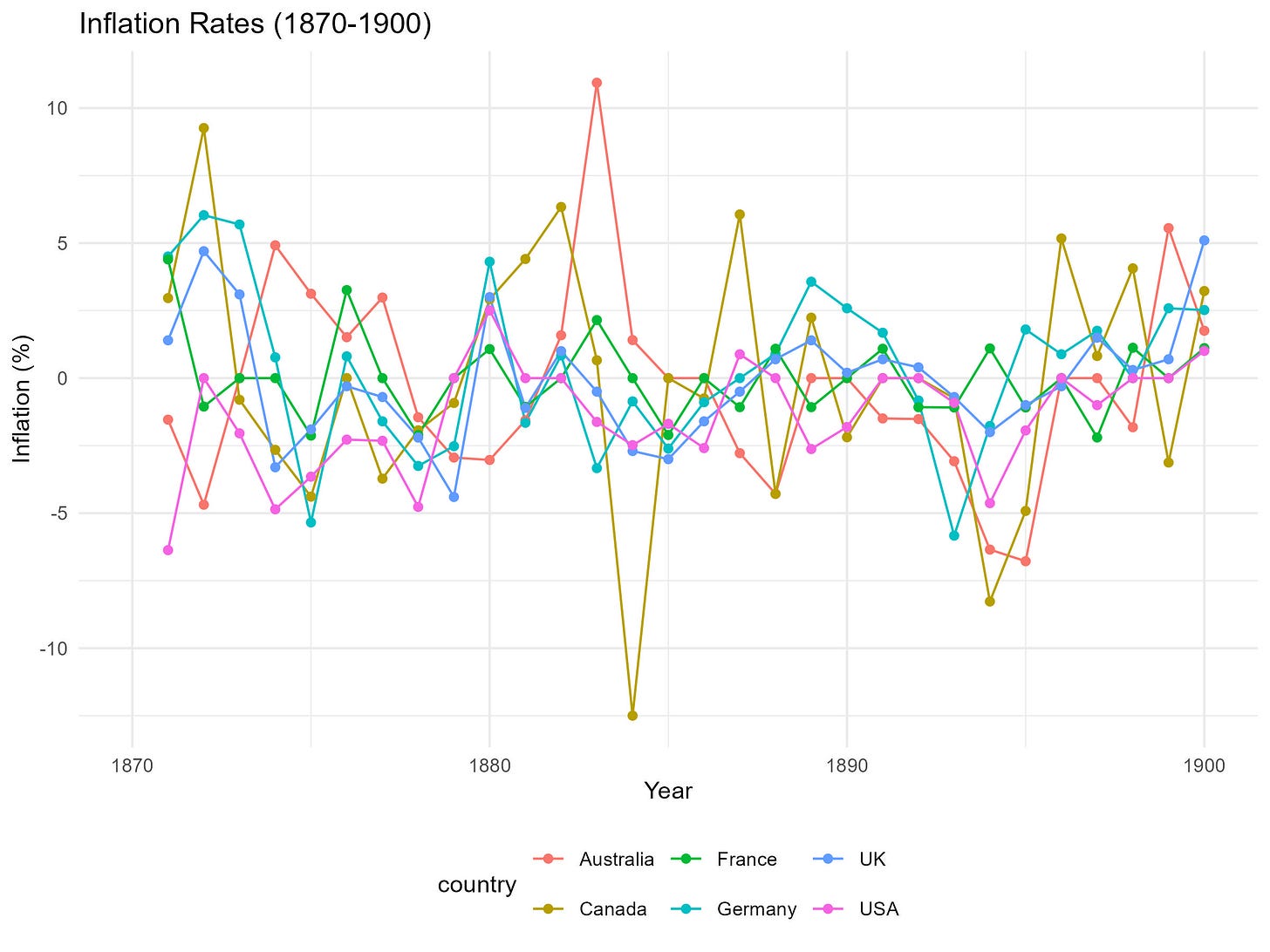

I’ll tell you more about the whole paper later. In the meantime, I thought it’d be interesting for people to see global inflation in the past, starting with the period from 1870 to 1900.

Global Inflation in 1870-1900: Deflation and Wide Variation

This is already a messy graph and only contains 8 of the 18 countries in the data. But it’s enough to convey two ideas: (1) inflation was much more volatile at that time than it is today, and (2) it was negative, i.e., deflation, about half the time.

It’s a good reminder that inflation is a lot less volatile today than it was before the 20th century. Also, inflation is generally positive today, whereas it was generally negative then. Most of the countries' inflation rates were below the zero line for the majority of the time.

While the chart gives us a feel for things, the data for all 17 countries is easier to grasp in a table, which I present below. The missing country from the total of 18 is Ireland, as there’s no data for it during this period.

Table: Inflation statistics for 1870-1900

This table shows the average inflation rates, the minimum and maximum rates, and the range of rates (max minus min) for 17 countries. For example, the average inflation in this period for the United States was -1.4%, with a low of -6.4% and a high of 2.5%.

Inflation was negative on average for 8 of the countries (i.e., 47% of the 17 countries), at or near zero for 7 countries (41%), and 1% or more for only 2 countries (12%).

Not only was the average often negative, but looking at the “Minimum” column shows us that some of those lows were really low. Japan hit a low -26.9%, for example. That’s serious deflation.

Finally, notice the variation. The “Maximum” column shows that Japan also had the highest inflation rate at 33.3% at some point, with Portugal a close second at 31.9%.

The final column, “Range,” provides a single measure to see how large the variation was, calculated as max - min. As expected, Japan had the largest swing of 60% during those 30 years. That’s hard for people to endure.

Comparing 1870 - 1900 to 1990-2020

I don’t have data all the way up to 2024; it stops in 2020, which misses the Covid-related inflation created by governments in most countries around the world.

To make visual comparisons easier, I first present the same graph with the same y-axis (i.e., from -15% to +15% inflation). You can see the difference immediately.

What should jump out is that (a) the countries generally move together2 and (b) inflation is generally 0 to 5% or so. At the end of the 1990s, you can see that some countries had slightly higher inflation. In particular, Australia had 7.3% inflation, and the UK had 7.5%. That’s about where their peak post-Covid inflation rates were as well, by the way.

You really don’t see persistent deflation. You see isolated instances, and they are in periods you might expect. For example, around the 2008 Financial Crisis, inflation spiked up just before and then dropped right after. Indeed, after that crisis, the Fed reduced money growth dramatically to bring inflation back to its 2% target for the longer term. That pink dot before 2010 represents -0.3% inflation for the USA and is a one-year anomaly.

Overall, you simply do not see inflation below 0% with any regularity. Deflation was very common before the 20th century, but it is not common today. Why not?

People Hate Deflation

In theory, central banks could target low but positive inflation, say 2 to 3%, just as easily as low but negative deflation, say -2 to -3% “inflation”. The reason they don’t is because people hate deflation.

A simple illustration should make this clear.

Imagine a world where inflation is targeted and kept at 3% as a general rule. People in that world would learn to set prices, contracts, and wages to rise by 3% every year. Now, imagine going home to your family after learning your salary for the next year.

Case one. You might have taken it easy last year and would explain, “Well, I didn’t push it this year, so they only raised my salary for next year by 3%, meaning we just break even with the cost of everything going up 3%.” In economic jargon, your real wage didn’t increase. You have 3% more salary, but everything costs 3% more, so “net,” you break even. There’s no real raise.

Case two. Now, imagine pushing it all year. You missed your kids’ school events, worked late nights, etc., and did secure a raise. You’d explain, “Well, I know it was hard on us all, but my work paid off. They raised my salary by 5%!” Knowing that all prices will rise by 3%, you have an extra 2%. That is, your real salary increased by 2%.

In theory, it works EXACTLY the same with deflation. It’s predictable, and you can plan. But imagine the family conversation if inflation were targeted and kept at -3%.

In the first case, with no real raise, you’d explain to your family, “Well, I didn’t push it this year, so they only lowered my salary for next year by 3%, meaning we just break even with the cost of everything falling by 3%.”

In the second case, you’d explain your 2% real raise this way: “Well, I know it was hard on us all, but my work paid off. They only cut my salary by 1%!” Knowing that all prices will fall by 3%, your salary only falls by 1% more. That is, your real salary increased by 2%. It doesn’t really feel the same, does it? People hate persistent deflation.

People often think that deflation sounds great because they only consider it in terms of the stuff they buy—lower prices in the stores. While that’s true, those store prices reflect the grocery owner’s wages. The same is true wherever you work. With lower revenue every year, employers have to pay employees less, too.

Remember, deflation lowers “all prices in an economy”. That includes your salary.

That deflationary period was so disliked in the United States that William Jennings Bryan ran for President in 1896 to move the country off the gold standard and onto silver (which was worth much less), thereby easing the painful deflation of the gold standard. You can read about it and Bryan’s famous “Cross of Gold” speech, where he argued, “You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.” (wikipedia link).

There were riots, protests, and bank collapses during this time. It was tough. The gold standard was a harsh and painful economic policy. How did we get to that point?

A Little U.S. and Monetary History

People are always looking for “sound money” and there is a recurring belief that countries should tie their currency to something “intrinsically valuable” like gold. The idea is that if your currency is pegged to something valuable, your currency will be valuable too. Even today, some people call for a return to the gold standard.

The idea that pegging to something highly valuable will make your currency highly valuable is true. To eliminate high inflation today, countries often peg their currency to the US dollar or Euro for that reason. Indeed, during this 1870-1900 period, many countries pegged their currencies to gold (the US did so only after 1879), which made their currencies very valuable. And that was the problem. It made the US dollar so valuable that each good you wanted to buy cost only a fraction of that highly valuable dollar. In other words, prices (i.e., $ per good) fell as US dollars rose in value, leading to deflation.

There is a deeper problem, however, with the notion that gold is somehow magical with “intrinsic value”. In economic terms, nothing has intrinsic value in the way people often mean. Value is determined solely by market forces—supply and demand.

If everyone thought gold was ugly, if it rusted, and if it were abundant, it would be worth very little. Gold’s value is determined completely by the supply of it and the demand for it. The same is true of the US dollar today. It’s just a little piece of paper whose value is determined completely by the supply of it and the demand for it.

The Silver-and-Gold USD Standard: 1792 - Civil War

The Coinage Act of April 2, 1792, established the US dollar as the nation’s currency and set the value of 1 US dollar equal to 371.25 grains of pure silver or 24.75 grains of pure gold. These values and the ratio they selected were based on the fact that, at the time, gold traded at about 15 times the value of silver (note: 371.25/24.75 = 15). Simplistically, 1 gold = 15 silver in the market3. (Friedman, 1992)

That might have been the right price in 1792 but soon thereafter gold’s value rose to 1 gold > 15 silver and people quit using gold for currency.

The Coinage Act only guaranteed that the government would buy gold or silver and give you a US dollar. It did not guarantee that the government would buy dollars from you and give you gold or silver. The reason is that this would have allowed for the following get-rich-quick scheme: Suppose in the market, 1 unit of gold was worth 16 units of silver, but the US government set dollar parity at 1 gold = 15 silver. You could buy 15 units of silver in the market, take it to the government, and trade it for 1 unit of gold. You could then take that gold back to the market and buy 16 units of silver, thus earning 1 unit of silver profit. Repeat this process thousands or millions of times, and you could earn millions (or, if you are already rich, buy 15 million units of silver). The US government would soon run out of gold and end up with a large stockpile of silver4.

People could get more for their gold in the market, so they only took silver to the US government to trade for US dollars. The US government also began issuing only US silver dollars—much of our currency was in coins back then—since gold was too valuable. People could have sold it on the market for more than 1 USD! We were effectively on a silver standard during this time.

Congress recognized this and revalued the currency in 1834. At that time, the market traded 1 gold for 15.6 silver, so Congress set the USD’s value based on 1 gold = 16 silver.

Sure enough, everything switched, and only gold was brought in for dollars. People stopped trading silver with the government for USD. Coins were minted in gold, and we were effectively on a gold standard until the Civil War.

The Civil War and Fiscal Dominance

When the Civil War erupted, the US government needed to finance massive government spending. It issued bonds (i.e., promises), but that wasn’t enough. Soon the US Treasury (remember, this is before the Federal Reserve) began printing money to finance the war. It couldn’t do this if the value of each dollar was set in terms of gold, so it had to abandon our bi-metallic currency standard. We went to “fiat” money, meaning, just printed and backed with the good faith of government.

This situation, where the fiscal side of government (in the USA, Congress; elsewhere, probably parliament) needs money urgently and forces the monetary side of government to print money, is called “fiscal dominance”. This usually happens during crises and wars. Most recently in the US and elsewhere we saw this during the Covid pandemic. It always leads to inflation, and it did so in the United States during and after the Civil War as well.

After the war, however, people wanted to return to “sound money” and insisted on a metallic standard again. When Congress reset the USD to the value of a precious metal in 1873, it forgot to include silver and only set it to gold5. The act went into effect on January 1, 1879, putting the US dollar on a gold-only standard for the first time in history.

Gold Markets and the Value of the Dollar

By fixing the value of our currency to something arbitrary like gold, the US government allowed our currency to strengthen and weaken based on market fluctuations, not just policy choices. That is what we see in this 1870-1900 period.

For the 1870-1880 period, inflation was basically negative. This was a period of intentional deflation to get prices under control after the War and saw average deflation of about 3% (i.e., -3% “inflation”). Inflation was near zero in 1879, 1881, and 1882 with only one brief spike to 2.5% in 1880. After 1879, we were on the gold standard, and inflation was generally negative or zero, only hitting 0.8% in 1887 and 1% in 1890.

With the U.S. switching to a gold-only standard, the demand for gold increased dramatically. Gold was needed for currency in the U.S., and this was a period of rapid growth, which required a lot of currency. Hence, our success plus the gold standard led to a massive increase in the demand for gold. As gold’s value rose, so did the value of each US dollar, and prices fell.

To add insult to injury, most of Europe was also emerging from war-torn times following revolutions like those in 1848. Also wanting sound money, most European countries adopted gold standards, further raising demand for gold.

Indeed, Friedman (1992) explains that the UK, France, Germany, Italy, Belgium, Switzerland, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, the Netherlands, Prussia, and Austria all switched to gold.

Friedman (1992) focused on gold versus silver and shows the following simple chart (Friedman, 1992, p. 66) to illustrate how much gold rose in value during this period, at least compared to silver. Remember, we started in 1792 with gold around 1 gold = 15 silver.

He marked 1873 as the year when the US officially legislated the transition to a gold standard and 1879 as the year we officially started. From that period onward, the price of gold rose dramatically, reaching about 1 gold = 30 silver around 1900.

The only likely reasons it didn’t go higher are twofold. First, major gold mines were discovered in California and Australia. Second, innovations in extraction technology, particularly using cyanide, allowed massive gold mines in South Africa to produce gold. For instance, in 1886, South Africa produced almost no gold, but by 1896, it produced 23% of the world’s gold (Friedman, 1992, pp. 104-105).

Increased demand raised the price of gold, but increased supply lowered it. Clearly, demand growth was outstripping supply growth—resulting in more increases than decreases—and this led to deflation in the US and other gold standard countries.

Conclusions

Hopefully, you found this interesting. In many ways, this is a positive story. We may not always get everything right, but monetary policy seems to have helped reduce the variation in inflation and eliminate chronic deflation.

Below is the table for inflation in the 1990-2020 period if you’d like to compare. You’ll see that, on average, inflation is low and positive, and the range is much smaller than before. That doesn’t mean there’s 100% success in all countries, but in general, we are managing inflation much better today than we did 100 years ago. That’s a good thing.

Thank you for reading.

Appendix Table: Inflation statistics for 1990-2020

References

Milton Friedman. 1992. Money Mischief: Episodes in Monetary History (Harvest Book). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Òscar Jordà, Moritz Schularick, and Alan M. Taylor. 2017. “Macrofinancial History and the New Business Cycle Facts.” in NBER Macroeconomics Annual 2016, volume 31, edited by Martin Eichenbaum and Jonathan A. Parker. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

The data is freely available for download here: https://www.macrohistory.net/database/

That’s a bit of an overstatement. They might move more together today, but they certainly look that way because in the 1990s all the central banks of these countries moved to an implicit or explicit inflation target of 2%. What you are definitely seeing is that they are all near their targets and try to stay there.

I’m ignoring units to simplify the language so I don’t have to write a gram or grain or Troy ounce or anything like that. So, really 1 gold = 15 silver should be 1 unit of gold = 15 units of silver where unit is the correct measure of gram, grain, etc.

Any time you fix a price, quantities adjust. I’ve commented in other columns on this and will do so again in the future for sure.

Some claim this wasn’t a mistake but a political “crime”. See Friedman reference and his discussion of “The Crime of 1873”. He discusses the politics of it at the time in detail. There doesn’t seem to be any evidence of an actual crime, just a political act that hurt some people and benefitted others. Those hurt called it a “crime”.

Very interesting. Great summary of money in the 1800s. Let me quibble about recent events. Saying the post-Covid inflation was government driven is half true. The supply chain problems arisen with restarting the economy were part of the story. And fiscal dominance is not the right description. Deficits and the debt are higher than we’d like, but no one doubts the ability of the government to pay its bills. If they did, inflation would not have fallen.