Interest rates, interest rates, interest rates

I must have 10 drafts that I started over the past weeks then stopped because something changed or I realized the topic was just growing way to big to deal with in a single column. Everything is changing daily and sometimes hourly.

I thought I’d take a second and just share, then, what I’m watching and worrying most about today: interest rates.

Photo by Kelli McClintock on Unsplash

There are two reasons that I am watching for rising interest rates. First, is that I worry world markets will lose faith in the US government’s fiscal stability. Second is that we are trying to close the door on international funding to the US by moving toward trade balance or, worse, surplus.

US Government Spending

Debt is more than 100% of GDP and our deficit is at all time, non-war highs around 6% of GDP and likely to stay there or even rise to 7% of GDP.

Here’s our government’s deficit to GDP (link).

The US had a surplus starting in 1929, but then ran a deficit of -5% of GDP during the Great Depression. It then dropped dramatically during WWII to over -25%. Post War, it turned positive and fluctuated around zero until the 1970s.

Starting in the 1980s it clearly moved more negative and stayed there until the 1990s. You can see the glimmer of financial hope in the late 1990s after major US government spending reform. Our government actually ran a surplus for a few years! Amazing.

Back to the ‘80s. That early 1980s period is when the economy hit a major recession and we fought massive inflation and tried to rebalance the macroeconomy. It was also a period of massive defense spending buildup to fight the Cold War with the Soviet Union.

It’s worth noting that a deficit of -5% of GDP was historically associated with THE GREAT DEPRESSION … let that sink in…. and during the early 1980s to fight a major recession and a Cold War. Reagan was heavily criticized in the 1980s for letting the deficit get so bad. George W. Bush was similarly criticized in the early 2000s for letting it hit -3% in the 2003-04 period during the War on Terror, Iraq War and so on. Minus three percent for all that!

A -3% deficit to GDP was considered really, really bad. Then the Great Financial Crisis hit and we seem to have lost our collective minds. The problems got much worse starting around 2008. The Great Financial Recession was followed by an expansion of government services, entitlements and national health care (in its many forms). We have never recovered from this unsustainable expansion of government.

Debt is like putting on weight. It’s easy to pile on and slow to get rid of. In the case of debt, you also accrue interest so it just grows and grows unless you actively pay it off which requires running an actual surplus! The next graph (link) shows the US piling on debt without any concern, it would seem. We are now over 100% of GDP.

We were already at 100% of GDP around 2012 and it continued to grow. That’s pre-Covid. Let that sink in too.

The problem is that we show no signs of slowing down. DOGE or no DOGE, cut some money or not, no one is actually reducing government spending for real these days.

Yes, economic growth will help pay the debt, but it does not solve the underlying spending problem. Debt has been growing by around 5-10% a year since 2010 or so. GDP will need to grow by more than that just to halt the growth of debt to GDP. GDP needs to grow more than that AND we have to run government budget surpluses to actually pay it down. And no one sees that happening anytime soon.

Here’s the US government’s own predictions. And, before you claim it’s politically motivated, this graph has looked more or less the same since before the first Trump administration. I used to share a version of it in my classes back in the 2010s when our commitment to government largesse put us on this path. Again, this graph is from the US government’s own budget office (link).

This is due to spending. Covid here is a bump, not the trend. Also, it’s not a revenue problem. Here’s the other CBO graph to see:

The top line, “Outlays” (spending), is rising and so is the bottom line, “Revenues”. Both are as a percentage of GDP. The side notes are worth reading: Interest outlays rise to 5.4% of GDP and outlays on health programs climb to 8.1% of GDP.

Simply put, this is unsustainable.

Debt and Deficits in Context

To finance that, the US government must either raise taxes, print money or borrow. Currently we borrow. And, when lenders become concerned about the credit worthiness of the borrower, they raise interest rates.

The US government has already been dropping in its credit ratings. Just search for “US credit ratings”. We’ve gone from premium and safe to ehh… a little less so. I worry that we’ll decline more.

So, if lenders worry about our credit worthiness because we vote for politicians to spend like proverbial drunken sailors, then demand for our debt declines, pushing down the price of our debt and that pushes up interest rates.

This is the first reason interest rates could rise. And this is a key reason I watch them.

But, for broader context, the US sells debt into the global debt markets. We have a lot of competitors in that global market because other countries are selling tons of debt too. They too want to debt-finance their overspending. If this trend continues, this should also raise interest rates as we all compete for a limited supply of funds.

Here’s the IMF’s note on global debt to GDP (link).

That “WEO” is their "World Economic Outlook” estimate. They make these calculations every year. This graph shows what they expected in 2019 compared what happened for 2020-2024 and as they see it going forward.

It’s important to note, again, that the expectation pre-Covid was already for growing debt to GDP. The Covid bump might be forgivable, but it doesn’t excuse the increased rate of growth post-Covid or the general trend pre-Covid. This is a long-running problem that just got put into high gear.

Everyone’s selling debt. Europe is struggling economically and also trying to increase defense spending in the face of an aggressive Russia and a less committed America. They need to borrow a lot.

Japan is struggling economically. Already at over 230% debt to GDP, they need to borrow more as well.

A sudden increase in countries peddling their debt in world markets - especially large economies like those in Europe, Japan, and so on - combined with growing US debt sales of less credit-worthy debt and we have trouble brewing!

This is the first reason I’ve been keeping an eye on interest rates. I worry about our fiscal sustainability and world markets one day backing off. For example, something crazy could happen like the US could irritate our major allies and they could decide to buy less of our debt. The Japanese and Chinese governments are the biggest governmental buyers.

Anyway, things can change rapidly and we are skating on ever thinning financial ice.

Trade and Capital Flow Reversals.

As I explained in a previous column, (Net Investment and Trade Deficits) the trade deficit1 and financial investment into the USA are intimately related. If you eliminate trade deficits you will eliminate net inflows of global investment into the USA. Again, I wrote on this previously as well (Did capital outflows from the U.S. already start?). Here I repeat myself but with a slightly different approach.

The more the US economy moves toward smaller trade deficits or even surpluses, the less global money will flow into the USA, net. If the US dramatically increases outbound investment we can still have lots of inbound investment but today we have a lot of inbound investment into America relative to our outbound investment and that would have to stop if trade balances.

One person’s investment funds is someone else’s savings. Here I’m using the economist’s restricted definition of investment as “investment into businesses, capital, equipment2, R&D, etc.”

The key then is people’s willingness to “save” money and provide investment funds for all the businesses around the world. When I have money in my hand, I can either use it to buy something to consume or I can save it3. Whatever I save gets used by a business to invest.

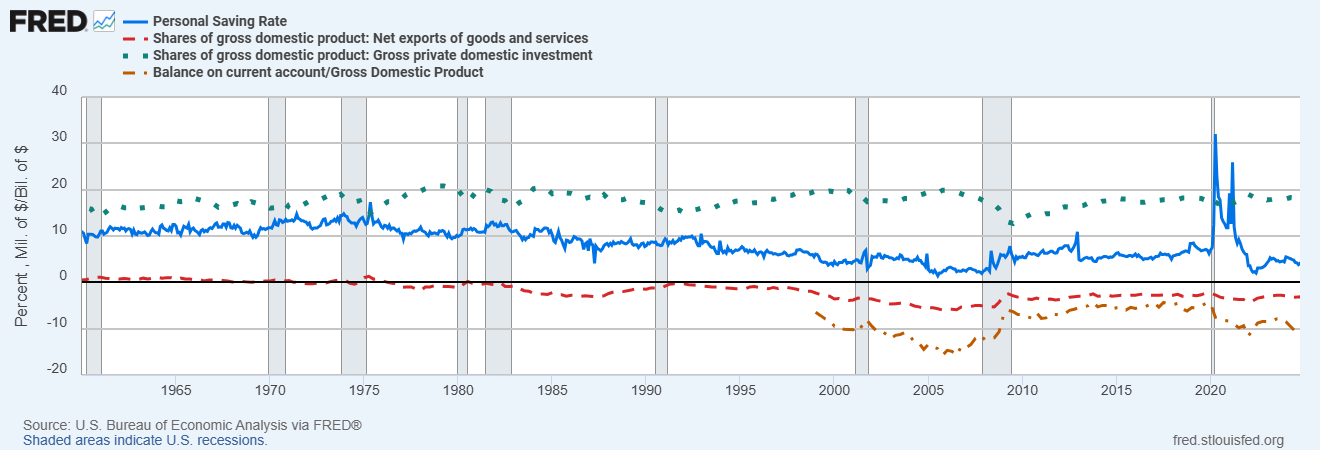

The US savings rate is around 5% today but our investment rate is around 17% of GDP. Now, these two measures don’t line up 100%, but they are easily obtainable and give you a sense of the issue. Here’s a graph (and a link).

The top, dotted, line is private investment as a percent of GDP. You can see that it’s pretty consistently around, say 15-20% of US GDP back to at least 1960. Where does the money for all that investment come from? Someone’s savings.

You can see that the domestic US personal savings rate4, the middle, solid blue line, was around 10% but began falling around 1980 and seems to have settled around 5%. If domestic residents aren’t supplying enough savings to finance all that investment, it must come from global markets.

You can see the global markets funding our investment in the bottom, dashed red line, net exports as a percent of GDP. You can literally see our trade deficit worsening as that savings rate drops from, say, 1980 onward.

The Covid spike was an anomaly. It’s due to that huge spike in money transferred from the government to the population which people mostly saved. That bled into inflation later.

The better measure to show this is actually the current account, but FRED only has data back to 2000 or so. If I add that to this exact same graph (link here), you can see it’s lower than the trade deficit and better accounts for that 15-20% investment vs 5% savings difference.

The current account includes the trade deficit plus “interest-type payments” to the rest of the world (see my footnote 1). In theory the current account equals the total amount of global capital flowing into the USA.

Think of US domestic savings plus global savings as the total amount of funds available for US domestic businesses and government to borrow. Businesses borrow it to invest in capital, equipment and R&D. The government borrows it to finance its deficit.

If you force that international door - net exports (or current account) - closed by requiring a trade balance, then US domestic savings must increase from 5% up to the 15-20% if you want to keep the same level of US investment.

If you add the amount the US government needs to borrow from that same market, then THE ONLY WAY to run those government deficits without either dramatically diverting funds away from US investment or requiring a massive increase in domestic savings to pay now for both US business investment and US government deficits, is to bring the funds in from abroad via that international door.

The Point

I guess you can see the point already. The supply of funds needed to finance both business investment in the USA and government deficits is fragile at the moment for three reasons. The first two are self induced. The third accidental, so to say.

First, the US government is committed to overspending at levels never seen outside of time of war or financial crisis. But the American voter insists our political representatives federally and locally give us as many goodies as they possibly can without us having to pay for it (today). We want foreigners to pay for it today and we’ll pay them back later. Later, however, is getting closer by the day. As it does, the US’s credit worthiness declines.

Decreasing our credit worthiness decreases demand for our debt, lowering its value in the market and requiring us to offer a higher interest rate to get people to buy it (i.e., lend us money).

Second, closing the international door to funds we need will obviously reduce that supply of funds. And, today, closing that door as much as possible seems to be popular across the US political spectrum.

Reducing the trade deficit decreases the supply of international funds to the USA. This means competing demands fight for a shrinking supply requiring everyone to offer higher interest rates to attract the funds to them.

Third, and returning to the IMF graph, other countries are doing the same. They are overspending and trying to borrow more in the same world markets we borrow.

Finally, other countries are additional demand for those same global funds. Raising demand will, again, require everyone to raise interest rates to attract those funds.

Conclusion

I’m watching interest rates. I don’t think we are in crisis today, but I worry more and more every day that we are closer than we think we are. Crises have a way of sneaking up on you then pouncing.

We see interest rates rise and say it’s nervous markets which is likely true. Then we see them go up because the Fed keeps them high to fight inflation which is also true. Then they go up because Germany borrows to finance more military spending which is also true. And so on and so on.

At the same time we watch the government decide to borrow more, raise the debt ceiling and refuse to reform anything fundamental. They are rearranging chairs on the deck of the Titanic.

It worries me every day. So, I watch the interest rates.

Side note: For anyone interested in reading accessible material about ways to fix our government spending problem, I recommend Les Rubin’s book, The Greatest Ponzi Scheme on Earth: How the US Can Avoid Economic Collapse (Amazon link), it’s solid, nonpolitical and contains tons of practical examples from countries that did solve similar government spending problems over the years. If you don’t want to buy the book, check out his site which is free and open. He writes on this all the time: Main Street Economics. To channel Les here, “there are solutions, just learn basic economics and use common sense”.

Thank you so much for reading.

Specifically “current account” deficits which are, in short, the trade deficit plus “interest-type payments” to the rest of the world.

Technically, for an economist, capital and equipment are the same thing, “capital”.

Okay, I can burn it or throw it away. We can call that “saving” with a -100% return. … Okay, I can give it away to someone in need. We can call that “buying” some personal peace of mind or good feeling for helping someone, that is, “consuming” that you did a good deed.

As a percent of people’s income, not GDP, and the two are not completely the same but close enough for a quick-look and to make my point.