Reasons to Question The Labor Market’s Strength

US unemployment dropped in the latest report! It went from 3.7% in October down to 3.5% in December. Everyone’s talking about the strong labor market these days.

If it’s “strong”, that’s being taken as a sign that the economy is also strong. By that people mean businesses are growing and their strong demand for workers leads to low unemployment. Hence low unemployment is taken as a sign of a strong economy.

Normally there’s a lot of truth to that, but there are two big reasons I doubt that more than usual today.

Reason One: Labor Supply is Still Low

First, the supply side of the market is still low. People still don’t seem to have returned to the work force post-Covid. (See my earlier pieces (part 1 and part 2) on the “Unemployment Enigma” for deeper analysis.) That pushes down unemployment numbers and up wages. Neither of those things, however, are being driven by a strong labor market. They are being driven by people not willing to return to work.

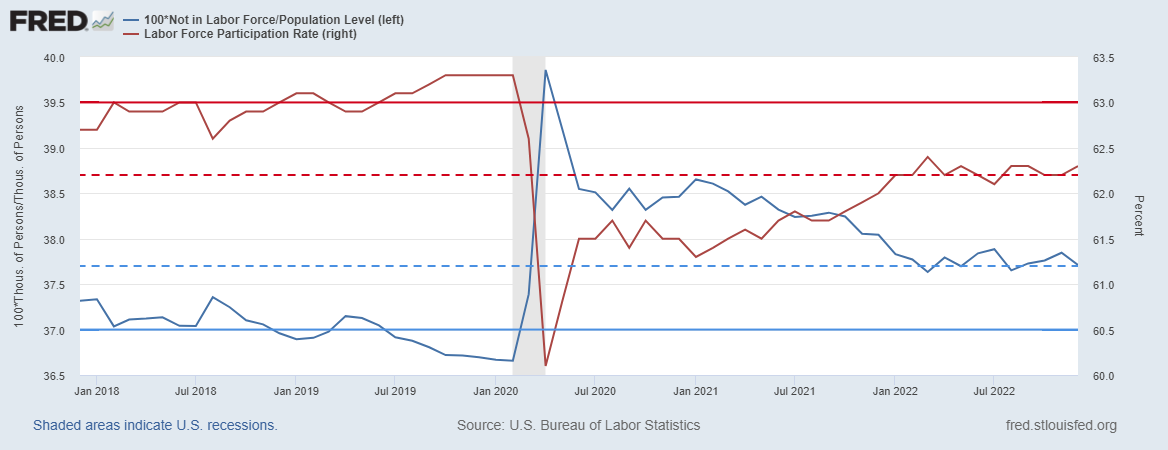

The solid red line at the top shows that labor force participation rate was averaging around 63% (right hand side of graph) pre-Covid. But it’s dropped to a little above 62% or so today. For an economy with 333 or so million people, that comes to about 3.3 million or so people that still have not returned to the labor force.

Those counted as not in the labor force – average represented by straight blue line (left side of graph) – was 37% prior to Covid and is still 37.7% or so today, representing 2.3 million people counted, but who are not in the labor force.

No matter how you look at this, it shows that the supply of labor is low. And, no matter how you cut it, that lowers unemployment and pushes wages up. So, demand might also be strong, but we can’t conclude that from the unemployment number alone.

Reason Two: Labor Is Relatively Cheap

We can think of businesses as buying three things: labor services, capital services and other inputs. Let’s go in reverse order.

Inputs

What’s happened over this last year or so to the price of most inputs that businesses use? That’s measured by the producer price index (PPI).

You can see the PPI was around 200 for a long time (despite the temporary drop around 2016). It went from around 200 just pre-Covid to peak at 280 early this year. That’s a 40% increase in the average price producers pay for commodities used in production. While it fell a little since the peak, it’s still 270 today, 35% higher than pre-Covid.

Capital

What about the price of capital?

For simplicity, we can think of “capital” as all the big things a business needs like large equipment, automobiles, buildings, etc. Because those are financed, economists consider the cost of capital to be the interest rate.

The federal funds rate is the “lowest” interest rate in the economy. It’s the Federal Reserve’s “policy rate”. It is the rate banks charge each other for overnight funds. Because it’s the base rate in an economy, all other rates generally move with it.

Pre-Covid is was 1.55% and today it is 4.33%. That’s a 179% increase in the cost of funds[1].

To summarize – and these are admittedly loose estimates for the costs of goods/inputs and of capital into production – the price of basic inputs rose 40% and the price of capital rose more than 100%.

How about wages?

Labor

The median weekly nominal wage in the USA rose from $951 per week pre-Covid to $1,068 per week today. That’s a 12% increase.

That means, if you are running a business, the cost of goods you use rose 40% and the cost of capital rose more than 100% but the cost of labor (i.e., wages) only rose 12%. Which would you buy more of?

Conclusion

Relatively speaking two things seem to be driving this labor market: (1) low supply and (2) relatively cheap labor. Neither of those tell us anything about how strong business demand really is in general.

Both help us see why the unemployment rate is extremely low these days. Labor is very cheap relative to all other inputs and businesses aren’t stupid.

[1] This is rough estimate for the cost of capital. Its actual cost depends on the business, how it’s financed, etc. So, instead of the full 179%, let’s just say, 100% or so. No matter how you look at it, the cost of capital rose a lot over this year as interest rates rose. And it should. That’s part of the Fed’s logic in raising rates! To restrict investment and consumption in an economy, both of which respond negatively to interest rate increases.