The Strong Economy is the Inflation Problem

Mixed messages continue to flood the digital airwaves as commentators, bankers, investment fund managers and others argue whether the Fed’s rate hikes were too high or not and whether we’ll have a recession. The saving grace they keep returning to is “but the economy still looks fundamentally strong and consumer spending remains strong”. That narrative is slowly changing as cracks and fissures appear in retail sales, industrial production and home construction falter. But I want to address the underlying logic, not the details

The “strong economy” is part of the problem. This is exactly the inebriated state of bliss caused by excessive monetary policy. The whole problem is that the economy is too strong.

Closed Systems

We can think of the economy as a closed system. Ignore the rest of the world for a minute and imagine that the US economy is an island alone in the world.

People work in groups - called businesses - to produce goods and services. Generally you work in one industry but buy stuff from other industries. Teachers aren’t usually taking their own classes, although Amazon employees or grocery store employees buy some of their own products.

But the trap of the closed system is that (1) you can only buy other goods at the rate you earn income from producing goods and services for others, and (2) other people can only buy the things you produce to the extent someone is willing to buy their goods and services and pay them.

Normally then demand for goods and services grows at the same rate as the growth in the production of goods and services. That is, you have to produce and sell goods to earn money so that you can demand other goods and services. In aggregate it all sort of washes out: one person’s sales (and income) is another person’s demand (and consumption).

Of course we additionally set some money aside to invest in new equipment for production and personally we likely save/invest for our futures and so on. We also have a government that consumes what we produce through our businesses (material for roads, to build schools, to make defense equipment, etc.).

And that’s where the “national income identity” comes from: Y = C + I + G. This says an economy’s total production, or income (because we only earn from producing things), must equal what we consume (C), what we invest (I) and what we give to the government (G).

The C + I + G part can be thought of as an economy’s total demand and Y as the total supply. Or, Y as the total income and C + I + G as the total spending of that income. It’s all the same.

Balanced Growth

As an economy grows, Y grows and this both generates income for people (as they sell those products) and provides the supply of goods and services people want to buy. The supply side of things then grows. But recall that our income comes from the act of supplying those goods and services and we can only demand more things if our income grows. In this system demand can only grow at the same rate as supply.

We all know from common experience that if the supply of something and the demand for something are relatively stable, then prices are stable too. To see that, think of a case where supply suddenly floods a market. Maybe there’s an over production of some sweaters at Christmas that stores thought would be popular but weren’t. In this example, supply increased a lot but demand didn’t. What happens? The sweaters are put on sale or sold in an online discount market. Either way, the price of those sweaters falls.

On the other hand, when a product is suddenly fashionable and everyone races to buy it, the opposite happens. Imagine a concert that sells out and yet the band - for whatever reason - even becomes more popular overnight. Now demand is through the roof, the supply of tickets isn’t changing and people will pay “anything” to get in, scalpers make money selling tickets at double, triple the price and so on. Price rose.

But when supply and demand are balanced and growing at about the same rate, the price neither rises or falls.

The same is true for the economy overall and when overall supply and demand are growing at about the same rate – which is the natural state of things because again our money to demand things comes from our producing and selling things other people want to buy – then the overall prices are relatively stable and inflation is basically zero.

Inside Money and Outside Money

If stores developed lines of credit or offered special tokens to customers to use, it wouldn’t affect the prices. Fundamentally it’s just allowing those same sales to take place. That “money” or credit is sometimes called “inside money” because it’s created inside the system just to facilitate transactions.

Outside money is what the government produces. US Dollars are “outside money”. They come from outside that closed economic system. Again, they are generally printed and distributed to facilitate transactions and by having a common currency you avoid the confusion you’d have if every store made its own inside money.

Economists say that money then becomes a “medium of exchange” and “unit of account”. The unit of account is the key piece here because once everyone accounts for stuff in dollars and then you can compare prices (it’s easy to compare two prices in dollars, but if one price is in dollars, another in Euros, another in precious metals, then it’s tough). That is, my store credits are counted in dollars, my amazon gift card is in dollars, so is my bank account and paycheck. Once that happens, the dollar becomes the common medium for all exchanges in the economy too.

A government just wanting to provide such a service – a unit of account – to facilitate the normal order of things and of course facilitate the payment of taxes, would issue money to the economy at about the rate of economic growth. That is, as the supply and demand side grow naturally, the government would print money at that growth rate and prices would indeed stay flat in general.

Getting Out of Balance: Too Much Spending and Too Much Money

The only way that demand can grow faster than supply in all markets for a sustained period of time is if something outside, like government money, ballooned up the demand side. That happened over the last two years.

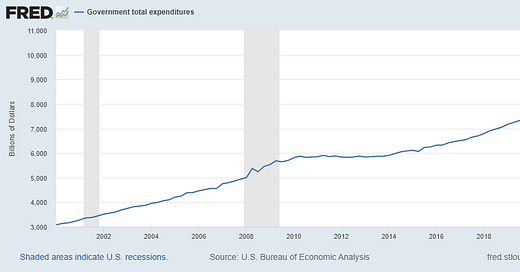

The US government spent nearly $5 trillion dollars – about 20% of our GDP – during the Covid pandemic intentionally trying to boost the demand side of the economy so businesses had consumers to sell to. Remember, normally you can only demand if you produced and sold something since that’s where your income comes from. When everyone locked down, leaving only essentially workers only, most people weren’t generating sales, revenue and hence incomes for themselves. The government tried to put money in people’s pockets and also bought stuff directly. In our Supply and Demand equation above, this is a big boost to the G part of C + I + G on the demand side of the economy.

Additionally some of that money was transferred directly to people to spend in an effort to maintain C in that equation.

The logic of this should already strike you. If people aren’t working, where would the “Y” (production) come from even if consumers had money to demand things?

Well, companies first ran down their inventories because they assumied the lockdowns would be short lived, but they weren’t. People are still only slowly returning to work. Supply was very constrained.

This happened globally too, so when we ran out of our domestic stuff, we tried to import more from other countries, but they were all doing the same. There just wasn’t enough to go around. Low supply combined with the same or higher demand got us higher prices across the board.

That was what the Fed hoped was “transitory inflation” about one year ago. They hoped that as people returned to work and production resumed, those prices would fall. And eventually they would have if we hadn’t flooded the market with cash.

Financing the Government and Money Mistakes

One quick question: where did the government get all the money for that massive stimulus? It had a few options: tax revenue, borrowing from domestic people, borrowing from foreign people, or printing money.

A moment’s reflection tells you they didn’t get $5 trillion by suddenly hiking taxes by $5 trillion. That would have been totally counter productive anyway. Give me $10 so I can give you $10 doesn’t leave you any better off.

A similar logic follows from domestic borrowing. Lend me $10 so I can give you $10 doesn’t help.

Borrowing from foreign people is an option and we did some of that.

But the biggest financer was the US Fed. Essentially the US government “borrowed” domestically but it did so by borrowing from the Fed. The Fed began buying $120 billion a month of government bonds. Additionally, the Fed printed an additional $1.5 trillion in funds that the Fed gave to other financial institutions. These are only pieces of the puzzle, but it gives you a sense of the magnitude.

The next piece was the continuation of the extravagant policies in 2021 and the Fed continuing to buy incredible amounts of US debt even until March this year. That kept the monetary tap pouring into the system even into this year and there’s really no way anyone can justify that, at least in my opinion. Fed Chair Powell admits now that they are scratching their heads to understand why they misread the situation so badly and caused inflation.

All these actions blew up the demand side of the economy while the supply side tried to catch up. Now the closed system was chasing its own tail. This is why it’s “fake demand” looking to buy way more than the economy can actually produce given current technology and capacity.

And that’s how we got to where we are today. The monetary mistake is that the Fed misread the tea leaves until very recently and is still behaving a little naïvely in my opinion.

Long and Varied Lags: Why Today’s Rate Hikes Won’t Stop Inflation Today

The final challenge is the one we are also struggling with today. Imagine a hose that pushes a giant ball through it. As the ball goes through the hose, you see where the lump is as it slowly moves along like a wave[1].

That’s the money flood going through the system. But there’s a delay between when the wave starts and when it reaches different parts of the economy. We say in economics that an increase in money affects the economy with long and varies lags. Historically about 6-18 months after the infusion of the cash. Now, this time the time has been sped up because of Covid shutdowns and the way money was added to the economy – via transfers directly to people like a “helicopter drop” of money from the sky. That was like a direct shot of adrenaline.

Last year’s monetary and fiscal stimulus came on top of the previous year’s, so there was a double wave coming down the pike. Are we seeing the first or the second wave? It’s hard to tell. Maybe they’ve combined into one giant wave of demand driving up prices… maybe the first was last year and the second is now… it’s hard to say.

But if that’s the cause, then inflation will only subside when the wave passes through. Higher interest rates may speed that up a little by stifling demand some (hence the concern that it’ll cause a recession), but fundamentally that wave must go through. When you hear things like “consumers still have lots of savings” or that they are “spending down their Covid savings”, that’s the wave. And, based on those reports, it’s not through yet.

Will the Fed’s Actions Help ?

So will the Fed’s recent actions help?

The Fed surprised everyone with a .75 basis point increase. Will that matter?

Yes, it will. But as I’ve argued elsewhere, nominal interest rates should equal inflation plus something. Even with these hikes, the federal funds rate is 1.5% or so. Inflation is 8.6%. When everything is said and done, if inflation returns to its normal 2.5%, then the federal funds rate should be 2.5% plus something. Let’s say 3%. It’s still not even half way there.

The Fed’s actions now are triggering interest rates to rise and this does stifle demand today. So that should slow the rise in inflation some, but again it will act with long and varied lags. That means we may see less demand today and businesses worried about the future will hire less, but the effect on prices is still some months away.

We haven’t touched the war in Ukraine and related energy prices. That’s going to continue for some time no matter what the US Fed does. By delaying any meaningful action, the Fed is now fighting inflation – which it must do and only it can do – but it’s doing it at the worst possible time.

We’ll have high inflation this year and also a recession. The pain is just now setting in.

[1] Other people us a “pig in a python” analogy but I always found that a little gross.