A Global Monetary Snapshot: Policy Rates and Currencies

In the last two weeks, the US Fed, the European ECB, the Banks of England, Australia, and Japan all had major monetary policy meetings. When it rains it pours, as they say.

Photo by Osman Rana on Unsplash

Remember, when one country raises interest rates it increases global demand for that currency, raising its (relative) value, but if every country raises interest rates together it shouldn’t change (relative) currency values.

Policy Table

The top of this table shows where things stand today, as of August 3rd. The bottom shows the previous recorded values, usually the previous month except for GDP which is reported quarterly.

I highlighted a few special cases where things are noteworthy/unexpected for some reason. Canada also hasn’t had a policy meeting lately, so I put them off a little separate on the right.

The FED and the US Dollar

US inflation numbers continue to improve. Headline inflation is now 3% (see my last column[1] for deeper comments), falling from around 4% as last measured. The FED, however, aims for inflation to be 2% , and thus, on July 26th, announced that it raised US interest rates by another 0.25%, taking the key policy rate from 5.25% to 5.50%.

As FED Chair Powell explained in the press conference, unemployment remains low – it fell from 3.7% to 3.6% – , the economy remains strong – GDP growth strengthened from 1.8% to 2.6% in Q2 –, and, therefore, the policy committee felt confident that another rate hike could be borne by the economy, and was needed to continue the fight against inflation.

He also explained that they would remain “data driven”, meaning they won’t say anything today about what they expect to do at the next meeting. They’ll look at the freshest data and decide. Also, he reminded everyone that inflation expectations are anchored, meaning that, when asked, most people believe inflation will eventually return to 2% “in the long run”.

These are all signs, in the FED’s opinion, that policy is working. Everyone should therefore expect the FED to either hold interest rates constant or raise them further until inflation hits 2%.

All else equal, raising interest rates should lead to a stronger US dollar relative to other currencies. Sure enough, following the announcement on July 26th there was a large jump in the value of the US dollar relative to an index of global currencies[2].

The ECB and the Euro

Europe continues to struggle more than the US. Q2 GDP growth is at an anemic 0.6% annual growth, down from an already weak 1.10% growth rate in Q1. Unemployment remains around 6.4% which is actually somewhat low for Europe[3] but inflation persists at 5.3%, farther from a 2% target than US inflation.

On July 27th, the ECB also raised rates by 0.25% to 4.25%[4]. The ECB also adopted the “data driven” language, a softening of the ECB’s language that market participants took note of. They also committed to fighting inflation, stating that “the key ECB interest rates will be set at sufficiently restrictive levels for as long as necessary to achieve a timely return of inflation to our two per cent medium-term target”.

The challenge in Europe is captured here:

“The near-term economic outlook for the euro area has deteriorated, owing largely to weaker domestic demand. High inflation and tighter financing conditions are dampening spending. This is weighing especially on manufacturing output, which is also being held down by weak external demand.”

The German economy – the biggest economy in Europe – is heavily reliant on exports, and global demand has been weak. Indeed, the Chinese economy, a major export market, has remained weak, as has global economic demand elsewhere outside the United States. For this reason, the ECB has been a little more cautious in raising interest rates, and potentially less effective at controlling inflation.

All else equal, however, this rate hike should have strengthened the Euro against most currencies, but it didn’t.

The graph[5] shows that the Euro weakened dramatically on the July 27th announcement. Notice that’s the same day the USD strengthened against a basket of currencies. It is very hard to know the true cause of the movement, but here’s my interpretation.

First, I find it helpful to think in terms of probabilities. Imagine that, on July 25th, you assumed it’s 50:50 that the US and Europe will both raise rates further over the coming months. Did these policy announcements change your beliefs? And, if so, how?

The US is conquering inflation but still have a ways to go to hit 2% inflation. The FED raised rates again, and is open to raising them again. US GDP and unemployment are strong. Therefore, the FED doesn’t need to worry too much about the cost of raising rates again. They seem to be slowing inflation, but not the rest of the economy. That’s about the best environment the FED could be in.

The EU is having less success conquering inflation, and the economy is weak. While it did raise rates on July 27th, it shifted from giving forward guidance to “expect more rate hikes” to a statement that it’ll be “data driven” and take each meeting as it comes. This is a weakening of the ECB’s resolve to keep rates high, and potentially raise them further.

Based on these new pieces of information, all else equal, it sounds less likely that the ECB will raise rates again, and equally or more likely that the US will. That would drive up demand for US dollars where returns (“interest rates” broadly speaking) are more likely to remain high or rise. Hence an increase in the value of the US dollar and a drop in the value of the Euro. Given that the USD rose against an index – a whole range of other currencies – tells me it’s more a story about US dollar strength than anything else.

The Bank of England and the Pound

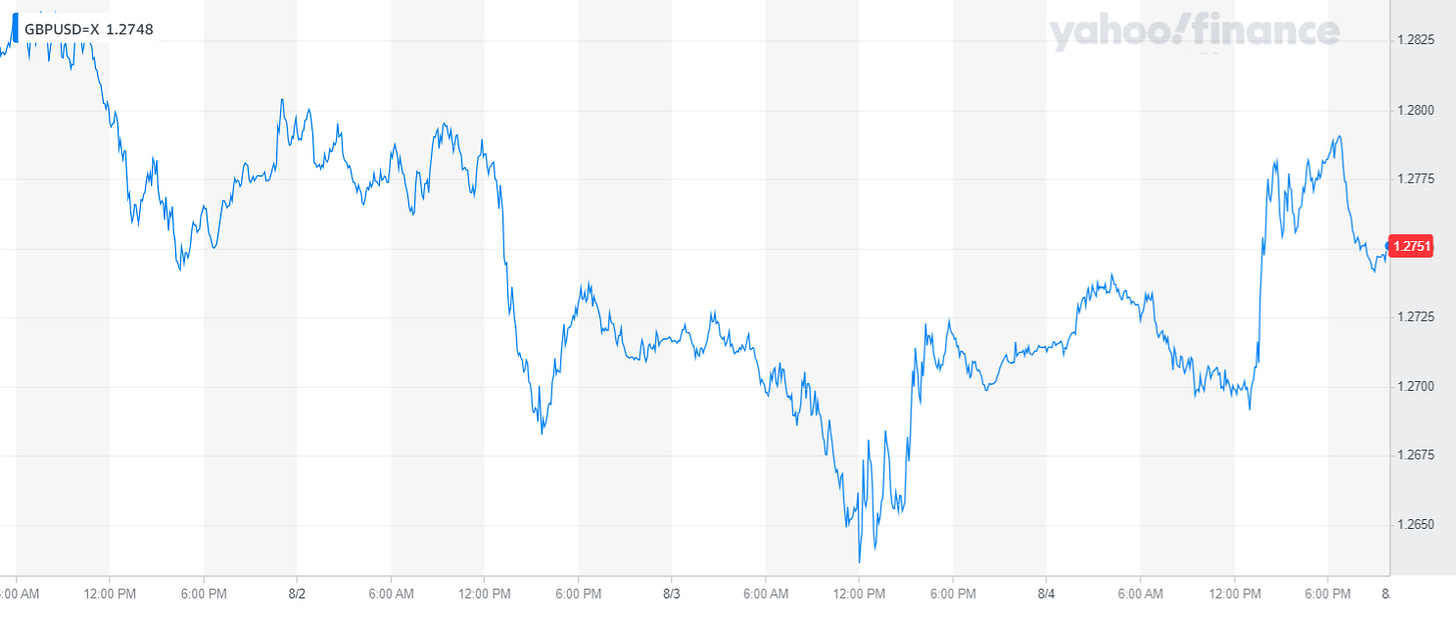

The Bank of England’s (BoE) meeting[6] was on August 3rd. The BoE also raised rates by 0.25% to 5.25%. UK inflation, however, is by far the worst among the major economies, at 7.9%. Economic growth is also the weakest at 0.2% for Q2. Additionally troublesome is that unemployment rose from 3.8% to 4%.

The UK is struggling. With an already weak and weakening economy, it will be politically very difficult to continue raising interest rates, yet more hikes are needed to fight persistent inflation. That is a rough place to be.

Like our thought experiment above, this suggests to me a 50:50 sort of knife edge in terms of expecting further rate hikes. They are needed more than in other countries to fight inflation, but are also more costly due to the weak economy. The effect on the British pound’s value relative to others ought to be small.

The BoE’s policy rate hike was on August 3rd (just right of center in the above graph). The British pound’s value was declining all morning prior to the meeting, and the rate hike announcement seems to have put the pound sterling back where it was. That’s a mild to neutral response.

Some negative US economic news came out at the end of the week, possibly explaining the sudden strengthening of the British pound at the end of the graph here.

But, I don’t know. That’s just my guess. Last week ended with Fitch downgrading the US government’s credit rating – hence weakening demand for US dollars – and a weak jobs report on Friday, August 4th. A weaker jobs report suggests the US economy is cooling, and might lead market participants to decrease their belief in further US interest rate hikes, again, slightly weakening demand for US dollars.

Australia and Canada

Australia and Canada are less influential in global markets, but both are interesting for different reasons. I won’t look at their currencies, but you can if you like (footnote has links[7]).

Australia and Canada are both experiencing relatively strong economic growth, although it slowed slightly in Australia. Nevertheless, both economies have been growing more than 2% all year long.

Unemployment is higher in Canada at 5.4% than in Australia at 3.5% while the opposite is true of inflation, which is higher in Australia at 6% than in Canada at 2.8%. Relatively strong economic growth, low unemployment, and higher inflation would suggest Australia should be raising interest rates further to fight inflation during a resilient economy, and Canada might consider a pause. But that’s not what happened: Australia held interest rates at 4.1% while Canada increased them by another 0.25% to 5%.

Honestly, I don’t know why. They are both traditionally committed to inflation targeting. Canada targets inflation of 1-3%, so they are within their range with headline inflation. But Australia has a target of 2-3% inflation and are nowhere near it at 6%.

I’ll dig more, and see if there’s something interesting to report in a future Global Econ article.

Japan: The Land of Monetary Mystery

We started in the relatively normal world of central banks battling inflation, some more successfully than others, by raising interest rates. We then moved to a stranger world where Australia is doing nothing, but has high inflation, and Canada is fighting inflation that is already in its target range. Then we get to the Alice in Wonderland world now as Japanese monetary policy.

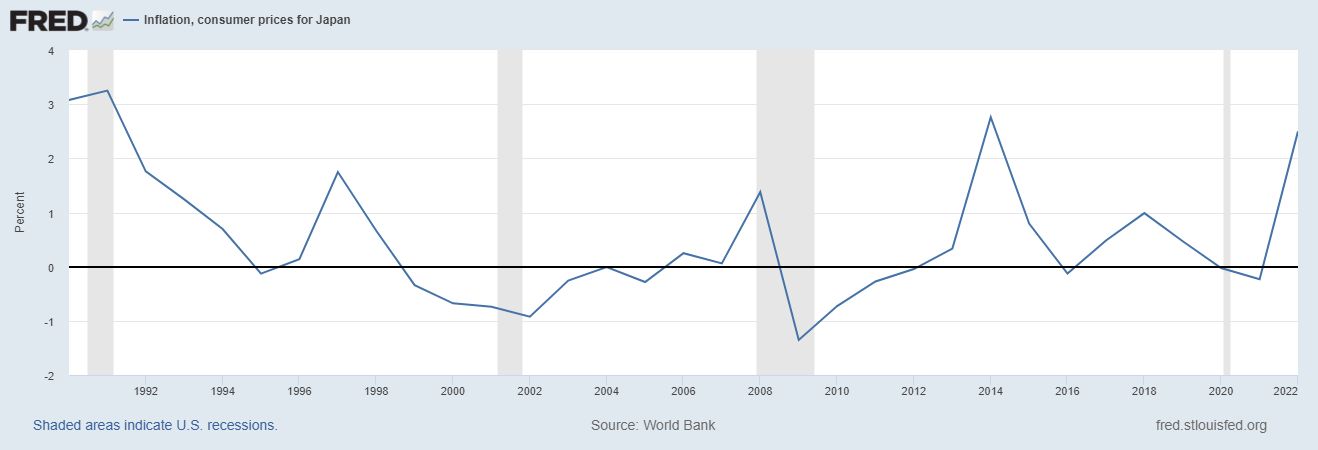

While most economies are struggling to get inflation down, Japan struggles to get it up. The Bank of Japan (BoJ) has a 2% inflation target. Inflation has been rising in recent months, going from 3.2% to 3.3% in the latest data. That’s well above 2%. And at the latest meeting the BoJ announced it will continue to keep interest rates negative, at - 0.1%.

To understand… well, to have a chance of potentially understanding… Japanese monetary policy, it’s important to recall that Japan has suffered from low inflation and bouts of actual deflation since the early 1990s.

The BoJ’s policy notes for their July 27 and 28 meeting comment that the BoJ does not want to lose a “golden opportunity to dispel the deflationary mindset”[8]. And so, they are letting inflation fly. Just looking at the graph we might guess they worry about inflation just spiking and then returning to negative/zero territory as it did in 2008 and 2014.

Central banks are also obsessed with managing people’s inflation expectations. The reason is that, if you can keep them anchored around your target, say 2%, then the people in your economy build 2% inflation into supply contracts, wage negotiations, and all pricing in general. If enough people do this, then enough prices will only rise by that amount. At least that’s the thinking.

The belief by many, and certainly by many at the BoJ, is that inflation is anchored too low, near zero. They want it around 2%, so breaking this low inflation mindset could be helpful to the BoJ over the longer term.

It’s funny to me that they still write in their own monetary report “The year-on-year rate of change in the CPI is likely to fall below the 2 percent level in the second half of fiscal 2023”. It seems to me that the BoJ itself can’t shake its own “deflationary mindset”.

And, like all central banks, they claim that none of the inflation or lack thereof is their fault. They explain, “The main reason why projected inflation for fiscal 2023 has deviated upward from the baseline scenario is that the cost-push from import prices has affected prices for longer than expected”. That is, prices are high today because of cost increases at businesses, mostly due to higher import prices. Elsewhere in the report they explain slower global growth is easing these import prices, and therefore they’ll fall, hence the concern of CPI falling below 2% in the future.

When I read monetary reports blaming everything under the sun for the rise and for the fall of the price level, I lose confidence in the central bank. My take is that the BoJ does not control short-run or long-run inflation in Japan[9].

The biggest move the BoJ made at its July meeting, however, was to publicly announce an easing of its yield curve control policy. This was the BoJ’s novel creation where they decided to control the entire yield curve by capping interest rates of different maturities, specifically 10-year maturity rates.

Recall the yield curve is just the interest rates on different maturity debt. Imagine walking into a bank, and looking at the wall where it shows different interest rates on loans. You can get an overnight loan, a loan for a month, a loan for a year, 5 years, 10 years and even 30 years. They’d all come with different rates. If you plotted all those rates on a piece of paper, that’d be a yield curve.

Yield curve control was a Japanese invention in 2016. The idea was that monetary policy only sets the short-term rate. They already set it below zero and yet inflation didn’t rise. So, their thinking went, they will try to lower all interest rates of all maturities, and see if that sparks inflation. (It didn’t.)

Relevant for me here are three things. First, other countries, including the USA, have been considering yield curve control too and “quantitative easing” – also a Japanese monetary invention – was partially a move in that direction. Japan’s policy successes and failures are therefore closely watched by central bankers and monetary researchers around the world.

Second, as I repeatedly remind everyone[10], anytime you fix a price, quantities will adjust. If you don’t want shortages and surpluses, the government must be willing and able to buy and sell the things it fixed the price of.

In an effort to generate inflation and then control it in Japan, the BoJ has tried to control many financial prices in the Japanese economy. Yield curve control includes caps of Japanese government bonds which requires the BoJ to be willing to buy and sell them. As result, the BoJ now owns a majority of Japanese government debt, about 2 trillion US dollars’ worth, along with 7% of the stock market – making the BoJ the largest single owner of Japanese stocks – and I’m told (and believe but haven’t confirmed) that it owns 80% of all new ETF’s (exchange traded funds) in Japan.

I worry that the US will try the same here. Prices are signals, and contain a lot of information. I can’t help but wonder what the effect is of central banks controlling more and more financial prices.

Anyway, the Japanese announced that they’ll ease controls on 10-year rates in Japan, effectively easing their yield curve control. If you follow financial news, you’ll see stories about this and some of their struggles with it.

A few articles from Bloomberg.com on market responses to the change in yield curve control. The titles alone tell you a lot (links are active but Bloomberg requires a subscription, sorry):

The third and last, but not least, concern for me is the effect the Japanese moves will have on US financial markets and US monetary policy. Some estimates suggest the BoJ’s extreme low-interest policy sent more than $3 trillion USD to US and European investments.

Will higher rates and an easing of controls mean some of that will move back to Japan? If so, then that will pull money out of US markets, raising rates on US debt too. The US government will face serious debt-related challenges over the coming months and years, and this just adds to that challenge.

Once again, it’s not clear that this is entirely a bad thing. Hitting bottom is said to be required before addicts change their behavior. Politicians – and the electorate who voted them in – became addicted to cheap debt in the past 10 years or so. The problem, of course, is that hitting bottom is nevertheless hard and painful.

Conclusions

I started with a reminder that higher rates in one country attract demand for that country’s currency, raising its value relative to other countries. But, when rates rise in multiple countries, it’s not clear what happens to their currencies’ relative values. Expectations of future rate changes, of the economy going forward and so on, all become more important. And, expectations are fickle things, making the currency markets more volatile.

That will remain the case for the coming 12 months, in my opinion. Will the US or Europe raise rates again? Don’t know. Each sign the respective economy is strong suggest more rate hikes to “cool the economy”. Each sign of a debt struggle in capitals around the world suggests less rate hikes, depending on how sensitive the central bank is to political pressure.

Inflation seems slowly to be falling in most countries, and the economies seem to be strong. That is a strange situation. On the one hand, that’s great news, and there is no necessary relationship between a slowing economy, higher unemployment, and less inflation. There are plenty of examples around the world of high inflation along with high unemployment and recession as well as other examples of falling inflation and growing economies. Let’s take the win. We have economies with falling inflation and strong economic growth.

On the other hand, when a central bank raises rates to fight inflation, the rate hikes generally slow the economy and lower inflation too. The process by which that happens is what all the debate is about. Today’s situation of falling inflation and strong economic growth suggests to me the debate will continue. At the very least it suggests that the standard mechanisms for this are not the dominant ones at play. Is that because Covid was such a weird time? For sure, yes. Is that because we’ve changed so much in our financial system since the 2008 crisis? For sure, yes. Hmmm.

Interesting times remain.

Thanks for reading.

[1] Global Econ, “3% Inflation: Who, What, When, Where, and Why”. https://globalecon.substack.com/p/3-inflation-who-what-when-where-and

[2] Source: Yahoo Finance. https://yhoo.it/45ymygH

[3] European unemployment has fluctuated between 7.5% or so and 12% since 1990. It was over 7% just prior to Covid. Anyone wanting a graph can see this one: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/fredgraph.png?g=17DLp

[4] The ECB technically has three rates and they raised all three by 25 basis points. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pressconf/2023/html/ecb.is230727~e0a11feb2e.en.html

[5] The graph is how much 1 Euro costs in terms of US Dollars. And the cost of Euros drops here precipitously. https://yhoo.it/3YCdTaN

[6] BoE’s statement: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy-summary-and-minutes/2023/august-2023

[7] Yahoo Finance for Australian dollar (https://finance.yahoo.com/quote/AUDUSD=X/ ) and Canadian dollar (https://ca.finance.yahoo.com/quote/CADUSD=X/ ).

[8] BoJ site: and link to the report directly (only 6 pages long): https://www.boj.or.jp/en/mopo/mpmsche_minu/opinion_2023/opi230728.pdf .

[9] See my June 26, 2023, Global Econ, “The Japanese Economic Warning”. https://globalecon.substack.com/p/the-japanese-economic-warning

[10] See my July 15, 2022, Global Econ, “The Problem with Price Controls”. https://globalecon.substack.com/p/the-problem-with-price-controls